This article was originally published the March 2020 issue of Apollo, before the museums it discusses were closed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston reopened on 23 May; the Menil Collection remains closed to the public.

In 1941, a young French couple, Dominique and John de Menil, fled occupied Paris for the United States. Settling in the modestly sized city of Houston, Texas, they began to put their wealth to good use – she was an heiress to the Schlumberger oil-equipment fortune – and threw themselves into improving their new hometown, which they found surprisingly international and open to ideas. Eighty years on, it is their 17,000-piece Menil Collection, opened to the public in 1987, that above all else draws cultural pilgrims to the city. ‘My parents knew the De Menils,’ Gary Tinterow says. Houston-born and -raised, Tinterow has since 2012 been director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), an institution that has one of the largest encyclopaedic collections in the US – and which will later this year complete an ambitious expansion project that began in 2012. As a child, he was taken to the De Menil home on social occasions. ‘I became aware of their art when they had a large mobile home parked on Rice University campus – with air-conditioning – and put on proper exhibitions on cubism, Picasso, Braque, Surrealism,’ he says. ‘I went to see them when I was at high school.’

Such largesse was typical of the De Menils. They believed that art was ‘primary’ to human life and helped to cultivate spiritual consciousness. They promoted religious tolerance, contributed to the life of the city, encouraged both existing art collectors and new ones: ‘They had a club,’ Tinterow says. ‘The De Menils bought the art, and members could then choose to buy it.’ They were also extremely active trustees of the MFAH, whose original museum building, which opened in 1924, was the first to be built in the state. ‘They guided policy and acquisitions in the 1950s and ’60s,’ Tinterow explains. It was the De Menils who in 1961 helped to recruit James Johnson Sweeney, founding director of the Guggenheim Museum, as director. He knew Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who had already added a dramatic, free-span exhibition space to the museum in 1958, and invited him back to add a monumental sweeping lobby with a gallery above and a theatre in the basement below. These are Mies van der Rohe’s only museum buildings in the US and remain untouched, still fit for purpose. Assuming – not without justification – that the De Menils would eventually present their collection to the museum, acquisitions were often made to complement it. ‘When they decided to go off on their own, it was a major shift,’ says Tinterow. ‘But we made up for it.’

The MFAH and the Menil Collection are a 20-minute walk from each other in the downtown Museum District, via Philip Johnson’s striking Chapel of St Basil (1997) and his other buildings at the University of St Thomas. After the De Menils struck out alone, the two museums developed very differently while both, in their ways, reflected the boom-town’s story. Houston was founded in 1836 by two brothers from New York state, shopkeeper John K. Allen and his bookkeeper brother Augustus, who came west with other adventurers to snap up cheap land. They bought 6,642 flat, dusty acres on the west bank of the Buffalo Bayou, a muddy stream that meandered south to the bustling port of Galveston on the Gulf of Mexico, 50 miles away. Named after a friend of theirs, the politician Sam Houston, the frontier town flourished. Entrepreneurs living in log cabins traded quantities of cotton and hides that arrived by wagon and, soon, on 17 railway lines. When ambitious businessmen funded half the cost of transforming the Buffalo Bayou into the Houston Ship Channel, which opened in 1914, profits soared. With the first oil extraction in the Houston area in 1901, wooden derricks began to dot the prairies while refineries soon lined the channel. Houston became the world’s energy capital.

Away from their offices, Houston’s early oil tycoons and business barons lived in homes with lush gardens that flourished in the warm, congenial months from September to April (the infamous heat strikes only in summer). They gave lavishly to their city but few were art collectors; these would emerge in the next generation, from the mid 20th century onwards. After the death in 1939 of Monroe Anderson, who with his brother-in-law William Clayton built up the world’s largest cotton brokerage, his charitable foundation funded a cancer research hospital that would become the kernel of the Texas Medical Center (TMC), established six years later on what were then the southern fringes of the city. Around this same time, air-conditioning in private homes became feasible, contributing to a housing boom and, between 1940 and 1950, a population increase of more than 50 per cent.

The Orange Trees (1878), Gustave Caillebotte. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Today, dozens of research institutions draw experts from around the globe to TMC, making it the world’s largest medical centre. Meanwhile, Shell Oil Company relocated its headquarters to Houston in 1971, leading the way for scores of major companies to establish a presence in the city. The citizens of what is now the fourth most populous city in the US are so international and culturally diverse that in 2000 the census found it had no racial or ethnic majority; furthermore, its ethnic diversity registers at every socio-economic level.

It is not tourists but local inhabitants who are the leading consumers of Houston’s world-class music, opera, ballet, theatre and visual arts. The diversity of the population is reflected in the multitude of museums and arts projects across the city. Asia Society Texas Center, for instance, established in 1979 to promote greater knowledge of Asia and its cultures, has a performance and art programme to rival its parent, Asia Society New York, and a building by Yoshio Taniguchi, completed in 2011, that stands beside any in this architecturally rich city; the steam that rises from its entrance canopy evokes a Japanese landscape painting. Then there are two impressive university museums, the Moody Center for the Arts, part of Rice University campus, and the Blaffer Art Museum at the University of Houston. Across in Third Ward, one of Houston’s historic African-American neighbourhoods, Project Row Houses was founded by seven African-American artists in 1993 as an engine for social change; it comprises 22 little wooden houses, a few of which are still family homes, the rest used for community projects (the project now makes use of further structures in the area, too). And in Buffalo Bayou Park, which runs through the city centre beside ten miles of the river, the cistern built in 1926 to bring drinking water to the city now hosts art installations.

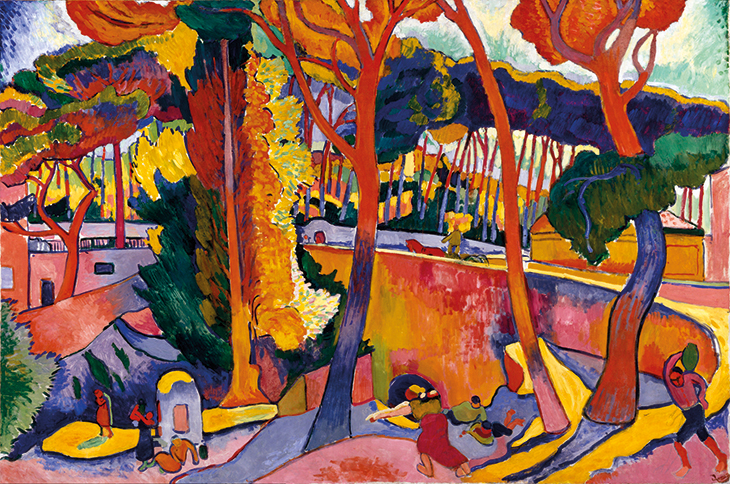

The Turning Road, L’Estaque (1906), André Derain. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The MFAH and the Menil Collection anchor all this artistic energy. Once the De Menils decided to build their own museum, they put Dominique de Menil’s dollars to work creating their own art campus. They selected Renzo Piano to design a home for their stellar collection of 20th-century art (from Matisse and Magritte to Twombly) and smaller holdings of antiquities, Byzantine, medieval and ethnographic art. Piano rose to the challenge of creating a building that was ‘small on the outside yet large on the inside’: in the elegant exterior, the extent of the space and number of intimate galleries come as a surprise on every visit. The 30-acre campus has four small buildings, too. The Byzantine Fresco Chapel – built for frescoes that have since been returned to Cyprus – has changing displays of contemporary installations. The other three are permanently devoted to a single artist: the sky-lit, interfaith Rothko Chapel (1971) hung with 14 meditative paintings by Mark Rothko (currently under restoration and due to reopen in September); the nine-room Cy Twombly Gallery (1992), also designed by Piano; and Richmond Hall, which houses a mesmerising Dan Flavin light installation that was Dominique de Menil’s final commission, completed in 1998, the year after her death. Finally, there is the latest addition, the Menil Drawing Institute, which opened in 2018 and is the first purpose-built institution of its kind in the US. Designed by architect Johnston Marklee and landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh, it chimes with Piano’s building – as refined in detail as the works it contains.

If the Menil campus realises its founders’ lofty aim for art to be experienced in an intensely personal, preferably spiritual way, and attracts international visitors, then the MFAH is more down to earth – a people’s museum. Most visitors are locals. ‘Their diversity continues to surprise and delight me,’ Tinterow says. ‘People come for relaxation and stimulation. They choose to come, they have to make the effort, get in the car.’ Having worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for 28 years, he makes a cutting observation: ‘Our visitors are more focused, engaged and aware than New York’s, where they seem glazed and shuffle through with a sense of obligation.’

Hunt Still Life with a Velvet Bag on a Marble Ledge (c. 1665), Willem van Aelst. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Founded in 1900, the MFAH got its first building 24 years later, with a neoclassical design by local architect William Ward Watkin. Then it took off: three expansions filled the road-constricted plot before the MFAH spilt across its boundaries – in the 1980s to a sculpture garden designed by Isamu Noguchi (now with site-specific commissions by Tony Cragg and Ellsworth Kelly) and then, in another direction, to a block of galleries by the Spanish architect Rafael Moneo, completed in 2000 and dedicated to European and American art. Five rooms display Old Master paintings from the Blaffer Foundation. Established by the oil heiress Sarah Campbell Blaffer in 1964, the foundation exists to promulgate its founder’s love of art – particularly by sending parts of its collection, such as its Goya and Hogarth print holdings, on tour to communities beyond the reach of major art museums. Works on display at the MFAH include Hunt Still Life with a Velvet Bag on a Marble Ledge (c. 1665 by the Dutchman Willem van Aelst, known for his ornate still lifes; its lavish use of ultramarine, made from expensive lapis lazuli, adds to its exotic luxuriousness.

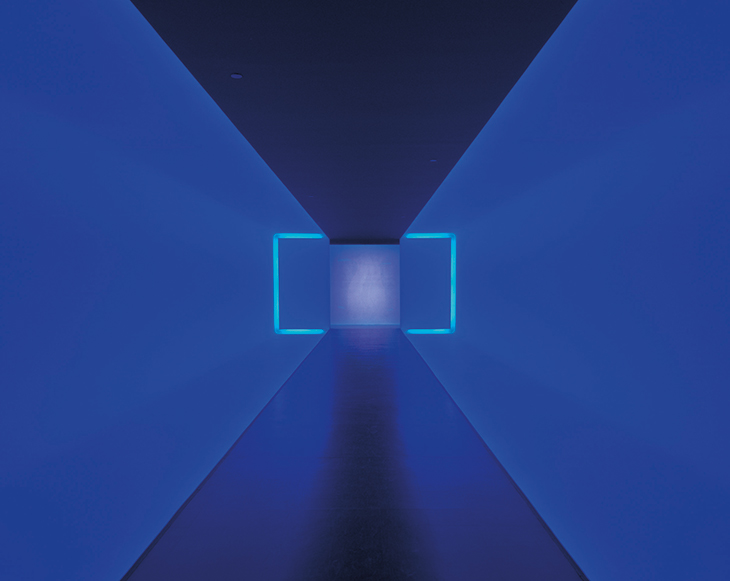

Here, too, is the Audrey Jones Beck gift of 70 Impressionist and Post-Impressionist pictures – among them Gustave Caillebotte’s The Orange Trees (1878) and exceptional Fauve paintings such as Andre Derain’s landmark work, The Turning Road, L’Estaque (1906), painted the year after he went to the south of France to join Matisse. Beck, who lived modestly despite inheriting a fortune from her grandfather, the renowned banker, developer and politician Jesse Jones, formed her collection specifically to give to the MFAH; from her grandfather’s Houston Endowment she gave $20 million towards the Moneo building. The tunnel to this building is one big artwork. James Turrell’s The Light Inside (1999) has walls of neon and ambient lights; walking through it is an all-encompassing experience, like floating, as the light changes from blue to crimson to magenta. People go back and forth just to enjoy it.

The Light Inside (1999), James Turrell. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

As well as being housed in a maze of buildings, the MFAH is a cultural institution of many parts. There is the museum, a major art school used by some 7,000 students of all ages, a research institute, two research libraries, a conservation studio, as well as myriad outreach programmes. ‘We are constantly looking at ways to engage the community,’ Tinterow says. There are also two satellite house-museums in River Oaks, a 15-minute drive away. Set in lush gardens shaded by trees such as flowering dogwood, silverbell, and soaring American sycamores and winged elms, they evoke the elegance of upscale Houston life in the 20th century. Both were designed by local architect John F. Staub: at traditional Bayou Bend (designed with Birdsall Briscoe and completed in 1928), 28 period rooms furnished with 17th- to 19th-century American decorative arts and paintings were created by Ima Hogg – whose vast fortune arrived when oil was found on her cotton plantations, and who campaigned against race and gender discrimination in the 1940s; by contrast, at Rienzi (1952), Carroll and Harris Masterson enjoyed their carefully collected European decorative arts – which the MFAH is augmenting – in a mid-century home with plate-glass windows.

Crown (1900–50), Ewe, Ghana. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

At the core of the MFAH, however, is its encyclopaedic collection. As Tinterow says, the museum ‘made up for’ the non-arrival of the De Menils’ collection. ‘We did not try to fill those lacunae, we did something of our own. Most obviously, we built the leading Latin-American museum collection in the world, setting standards in art, acquisition and publication’ – the museum’s International Center for the Arts of the Americas (ICCA) focuses on 20th-century Latin American and Latino art. Then there are the dazzling roomfuls of African, Indonesian and Pre-Columbian gold, assembled by Alfred Glassell Jnr (1913–2008), founder of the Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line Corporation. Wandering through them one encounters art that is often underrepresented in museums or kept in store: a gold crown (1900–50) made by the Ewe people, who live mostly in the coastal regions of Ghana, blends European style with indigenous ways of depicting an elephant and antelope to illustrate a pithy proverb: the elephant may be big, but the little antelope is wiser. The MFAH has also started to embrace Islamic art, and in 2012 Tinterow struck a deal that has led to a long-term loan of 250 objects from the remarkable al-Sabah Collection in Kuwait. Among the museum’s own acquisitions is a delicate 12th-century bronze incense burner from Persia, shaped like a cat and with a removable head for putting in the expensive incense ingredients – an object that gives an idea of exceptional achievements in metalwork across the Islamic world, from Spain to India. The museum’s current exhibition of new acquisitions and gifts, ‘Radical: Italian Design 1965–1985, The Dennis Freedman Collection’ (until 5 July), shows it to be establishing a foundation collection for this field.

Incense burner (12th century), Persia, Seljuk dynasty. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

It’s hardly surprising that the MFAH needs even more space – or that it has raised more funds than it needs to pay for a massive, four-part extension. In a fundraising campaign led by Richard Kinder, chairman of trustees and co-founder of one of North America’s largest energy infrastructure companies, most of the $472 million has been raised locally (the goal was $450 million). A new conservation building, art-school building and public plaza are complete. And on 1 November, the Nancy and Rich Kinder Building opens, designed by Steven Holl Architects and providing more than 100,000 square feet for displaying the museum’s collection – in particular what Tinterow describes as ‘our very strong collection of modernist abstraction from the beginning of the 20th century to the present, in the same league as the Met, Chicago, LACMA’. In these airy new spaces visitors can look forward to enjoying more of the MFAH’s American art, from Mark Rothko’s familiar Red and Pink on Pink (c. 1953) to lesser-known pieces such as American Dream’n (2009) by Fahamu Pecou (b. 1975). Such works complement and continue the museum’s strong modern art holdings, which include Constantin Brancusi’s A Muse (1917), an adaptation in bronze of his 1912 version, Pablo Picasso’s Woman with a Large Hat (1962) and two remarkable commissions by Nelson Rockefeller in 1939 for the grand salon of his New York apartment: soaring fireplace murals by Fernand Léger and Henri Matisse (the latter is on long-term loan to the museum).

Stroll along the avenues of live oaks, with their spreading boughs, and across the Rice University campus and you’ll reach the local sunset hangout on the lawn in front of the music department. James Turrell’s Twilight Epiphany (2012) was given by Suzanne Deal Booth, a Rice alumna who worked for Turrell and helped build his first Skyspace at MoMA PS1. This is the only two-storey Skyspace and the first to be engineered for acoustics, which the music students experiment with. In a square pavilion, LED lights in tune with the dwindling sunlight cast floating colour over the walls, creating an ethereal experience. The very keen can get up early and experience it at sunrise, too.

From the March 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.