Few museums are so undeservedly little known outside a specialist or local audience as the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst (MOK) in Cologne. Today, its interlocking cubes and long, low glass pavilions – designed in the 1970s by Le Corbusier’s Japanese pupil Kunio Maekawa – slot unobtrusively into its urban-pastoral setting around the Aachener Weiher, suggesting a seamless synthesis of East and West. It is a perfect expression of the intentions of the museum’s visionary founders, the collector and autodidact Adolf Fischer and his wife, Frieda (née Bartdorff). For this institution, founded in 1909 and originally opened in Cologne’s museum quarter four years later, was not only the first museum in Europe devoted to the art of the Far East, but also the first to consider its material fine art rather than ethnography, equal to the Western tradition.

‘It still seems bold to seek to place East Asian art on a level with European art,’ Frieda Fischer wrote in her diary in 1902, ‘and there is still no museum in Europe dedicated to this art. We are seeking to go along untrodden paths.’ Describing the couple’s visits to innumerable museum and private collections across Europe and in the United States, she continued: ‘Nowhere, though, has any attempt been made to provide a unified picture of East Asian art as a whole, or to present it in its phases of development. But this is our endeavour.’

The terrace of the 1970s museum building, designed by Kunio Maekawa, on the edge of the Aachener Weiher, Cologne. Photo: Alexandra Malinka, Dusseldorf

Prescient, too, was their notion of how visitors should experience the works of art the pair had crossed the globe to collect. ‘We shall not erect a princely palace for this art, but rather a quiet, elegant treasure-house which will itself be silent while letting the works of art speak. Our plan provides for no prestigious exhibition rooms or pompous staircases, but silent rooms, inviting visitors to immerse themselves in the art.’ It is a mission statement that might have been written today. The Fischers’ ethos of open-minded dialogue with the world remains relevant, even as Frieda Fischer’s persecution by the National Socialists in the 1930s and ’40s serves as a reminder of past intolerance. The whole story of the museum’s genesis, destruction and eventual rebirth is remarkable.

This tale begins not in Germany but in Austria. Adolf Fischer, the son of a wealthy Viennese industrialist, was 17 at the time of the Vienna World’s Fair of 1873, when Japan, newly reopened to the West, made its sensational first appearance at an international exhibition. A taste for Japonisme in all its manifestations swept through Viennese society in its wake, but it was not until 1892 that Fischer first visited the country as part of a world tour. Such was the impression it left on him that Japan would from then on be ‘the axis around which my life would turn’. Subsequent trips followed, including his and Frieda’s honeymoon tour of 1897. By 1900 the couple had amassed sufficient quantities of Japanese art that more than 700 pieces could be shown at the Vienna Secession exhibition.

By this time living in Berlin, the Fischers gave the collection to the state of Prussia in return for an annuity and, thus liberated, the intrepid travellers took off via Burma and Japan to China and later Korea, recognising the importance of these countries to the culture of Japan from the collections held in Japanese museums.

Yongzheng imperial bowl with overglaze enamel (c. 1723–35), Qing dynasty, China

It is hard to imagine now the difficulties they faced, practical and scholarly. While Japan had been relatively comfortable, travelling across China from the port of Tsingtao (Qingdao) was gruelling and sometimes dangerous. To learn more about their chosen subject, the Fischers visited sites and museums and private collections, reading what they could find written in German, English and French on art, architecture and indigenous religions, and taking copious notes. Their connections with directors of national museums opened many of the right doors.

This was a period of European colonial expansion – and the German empire was determined to follow the British and French in exploiting the weakness of Chinese imperial power in particular to gain access to resources and markets. A secondary goal was the establishment of collections that reflected the country’s wish to be seen as a world power, and in 1904 Fischer was appointed for three years as the ‘Academic Specialist at the Imperial Embassy in Peking’ to research the arts of China, Japan and Korea and assist German museums in their acquisition of ethnographic and ‘religious-scientific objects’. Meanwhile he continued to collect at his own expense for his art museum, the planned location of which was at this point Kiel.

It was only in 1909, when it became clear that the northern city was in no position to fund and maintain the museum, that Fischer settled instead on Cologne. A Circle of Friends comprising prominent local citizens was formed the same year, and with their funding the Fischers undertook further trips to build the collection. To save time, Adolf Fischer would have dealers bring objects to their hotel room, and then anything interesting would be kept and he would go to national museums in search of comparable examples, taking with him to lend a critical eye trusted craftsmen and restorers who understood traditional materials and techniques. Even around the turn of the 20th century, fakes were legion.

Bodhisattva Jizo with votive offerings (1249), Koen, Japan

One of his greatest acquisitions was the Japanese polychrome wood statue of the Bodhisattva Jizo, which Fischer saw in Nara in 1911. Recognising it as interesting and early – he thought it 8th or 9th century with a later base – he went to the city’s museum and found something comparable before making the purchase. During restoration work in 1983, the statue’s secrets were discovered: inside the hollow figure were thousands of votive prints with depictions of Jizo and the Amida Buddha, hand-copied sutra texts, a Chinese Song dynasty printed edition of the Lotus Sutra and a relic, two gilt Buddha statues, a coloured miniature version of the Jizo and a dedicatory inscription. The latter revealed that Koen, one of the most celebrated sculptors of the Kamakura period, had made the statue for the Jizo-in Temple in Kyoto in 1249, a commissioned copy of a 10th-century piece that had been damaged in a fire – hence the stylistic elements of two different centuries.

Fischer was occasionally prepared to compromise. Despite its damaged and repaired state, for instance, after careful examination he decided to secure for the museum the masterpiece that is a Japanese hanging scroll of 1392 painted in ink, colour and gold on silk, and depicting Buddha entering nirvana. Over the course of some 10 years spent in Asia, and for subsequent European purchases, he focused on Japanese and Korean Buddhist painting and sculpture, Chinese stone sculpture, Chinese and Korean ceramics, literati and professional painting, Japanese woodblock prints, plus Chinese, Japanese and Korean lacquer, sword decorations and painted screen panels.

Hanging scroll depicting The Entry of the Buddha into Nirvana (1392), Japan

On the recommendation of Josef Hoffmann in Vienna, Fischer chose the young Josef Frank as the designer for the interiors of the new museum. The result was spare, clean and remarkably modern. The minimalist display cases, which borrowed from Chinese and Japanese furniture, were also progressive in allowing the visitor to view objects in the round and to wander and make comparisons at their leisure.

Adolf Fischer died suddenly, in 1914, a few months after the museum opened. Under the terms of the foundation agreement, which gave the Fischers a stipend in return for their collection and an extensive library, Frieda succeeded her husband as director and established herself as an authority in her own right. In 1921 she married the lawyer and senate president Alfred Wieruszowski, with the result that 16 years later she was hounded out of office on the grounds of his Jewish ancestry, denied her stipend and indeed all civil rights. The publishing in 1938 and 1942 of the diaries of her travels with Fischer in Japan and China can be seen as a bid to save the couple from deportation to a concentration camp; it did seem to shame the authorities, but she and Wieruszowski both died, impoverished, in 1945. The museum building had been destroyed in an air raid the previous year, and while most of the contents removed for storage to salt mines survived the war, the smaller items deposited in a bunker in Cologne disappeared.

It was not until 1951 that the museum regained a specialist director. Professor Werner Speiser spent 15 years unpacking and cataloguing the losses from a collection that he would never see in its entirety and which was to remain in store for 33 years, keeping the memory of the museum alive by arranging modest exhibitions in its temporary host institution.

The decision taken in the 1960s to appoint Kunio Maekawa to build a new museum reflected the growing prosperity and optimism of this cultural and economic capital of the Rhineland. Referring to Japanese timber-frame architecture and incorporating Japanese materials, Maekawa’s buildings are set around an inner courtyard with rocks, trees and water designed by the sculptor Masayuki Nagare in the tradition of Zen Buddhist temple gardens. MOK’s collections, meanwhile, have grown to reflect the generosity of its supporters, the city and the state, for this institution, with its still very active Circle of Friends, has always been a private-public partnership. ‘Alles unter dem Himmel’ (‘All under Heaven’), an exhibition marking the 40th anniversary of the museum’s reopening (until 30 June), celebrates the objects that have enriched the collection over the past four decades. It includes purchases, gifts and permanent loans, as well as restorations that have revealed the full glory of some of these works of art for the first time.

The acquisition in 1999 of the outstanding collection of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy amassed by the academic publisher Heinz Götze (for what now looks like a miraculously modest sum of DM1.5m) transformed the museum’s holdings in this field into the finest in Europe. Here, for example, is the Poem and Reply Poem by the great Song calligrapher and scholar-artist Mi Fu (1051–1107).

More recently, the museum has concentrated on strengthening its collection of Chinese Buddhist sculpture, and the fruits of this project stand resplendent in its main gallery spaces. Among these acquisitions, loans and gifts made in stone, bronze, dry lacquer, stoneware and iron is a late 7th- or early 8th-century Tang dynasty grey limestone figure of Laojun, the deified Laozi, credited as the founder of Daoism.

Archaic Chinese ritual bronzes and Chinese classical furniture came as gifts from Hans Jürgen von Lochow. Particularly fine are the Shang dynasty ceremonial axe and ritual wine vessel of jia type, both dating to the 13th century BC. From the bequest of Kurt Brasch, meanwhile, the collection gained important examples of Japanese ink painting. Another significant addition to the core holding is the early Chinese pottery acquired from the collection of Hans Wilhelm Siegel. An imperial bowl decorated with scrolling peonies against a rare ruby-red ground – with a Yongzheng mark, dating to 1723–35 – is the latest gift from the Friends, in honour of the 40th anniversary.

Ceremonial Yue-type axe (13th century BC), Shang dynasty, China

Enhancing several areas of the collection, however, are works on permanent loan from the vast holdings of the Peter and Irene Ludwig Foundation – Chinese sculpture, furniture, export porcelain and a beguiling group of Tang dynasty ceramic mingqi, or funerary goods. ‘Sometimes loans are better than gifts,’ explains the current director, Adele Schlombs, recognising their role as potential bargaining tools.

As for restorations, these have been achieved largely through imaginative international collaborations. Since 2006, for instance, the Tokyo-based National Research Institute for Cultural Properties has staged annual workshops in the museum, enabling some 179 conservators and students from 17 countries to gain practical experience of restoration and consolidation techniques relating to lacquer work, mother-of-pearl inlays and hanging scrolls. Some 40 Chinese paintings have also been restored in the Shanghai Museum, and about the same number in Tokyo and Seoul. One hanging scroll could not return to Tokyo for restoration, and that was the late 14th-century Immovable King of Esoteric Knowledge, representing Fudo Myo-o with a sword with a dragon coiled around it, which gave the deity the power to assume any form he liked. Recently revealed to be registered as Important Cultural Property, it had been bought in good faith by Fischer in Kyoto in 1912. For this scroll, the National Research Institute arranged a restoration in Leiden, funded by the Sumitomo Foundation.

Schlombs has seen fit to be candid about all aspects of the museum’s history and collections, not only telling the story of the shameful treatment of Frieda Fischer for the first time, but also highlighting instances of looted and racist material in the collection. MOK owns the ancestor portrait (1776) of General Mingliang, for instance, one of the images of war heroes commissioned in the Western style from Jesuit priests for the Qianlong Emperor’s Hall of Purple Light in the Imperial City in Beijing, and plundered by German troops during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900–01 (see contents, p. 11). Also on display is a series of European-style miniature paintings made in Canton as souvenirs, which reflect the convenient new colonial view of the Chinese as decadent opium-eaters or brutal barbarians in need of civilisation.

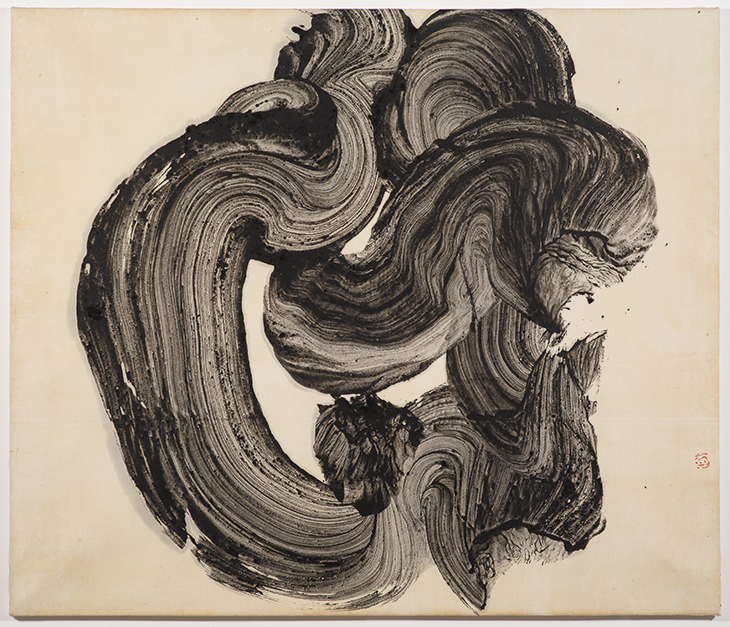

Haha (Mother) (1960s), Inoue Yuichi

Telling the story of the dialogue between East and West is at the core of the museum’s mission. As well as obvious examples such as a piece of Chinese export porcelain used as a prototype by the fledgling Meissen manufactory, or the kinds of Japanese prints that influenced so much European art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we also find the likes of a hanging ink scroll by Takeuchi Seiho, who studied Western art in Europe and whose atmospheric and ‘impressionistic’ ink mountain landscapes reflect a reciprocal borrowing. The narrative continues through Western gestural abstraction and the work of, say, Paul Klee, who was inspired by the verbal and visual imagery of calligraphy and symbols from the poem-paintings of Chinese literati. That this is a living tradition is perfectly expressed as works by the Japanese avant-garde calligrapher Inoue Yuichi or the Korean minimalist Lee Ufan fit seamlessly into the historical displays. A set of the former’s works from the 1960s, including the frozen-ink character Haha (‘Mother’), was acquired to mark Adolf Fischer’s 150th birthday.

It might have seemed that the Fischers’ battle to champion East Asian art as a preeminent fine art tradition with a history of connoisseurship and aesthetic theory far older than that in the West was long since won, but the recent announcement that the holdings of the Museum für Asiatische Kunst in Berlin are to be integrated into the city’s Humboldt Forum alongside ethnographic, African, American and Oceanic collections, and that its retiring specialist director was not to be replaced, appears to be a step backwards. MOK is now not only the first but also the only museum in Germany devoted to East Asian art.

From the February 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.