In 2007, fishermen on the Loire were disgruntled by the arrival of what appeared to be a melting boat in their midst. Misconceivable, an artwork by the Austrian artist Erwin Wurm, was installed on a canal-side lock as part of Estuaire: a 60km-long art trail leading down the Loire from Nantes to the city of Saint-Nazaire on the coast. When, after three years, the ‘Bateau Mou’ (or ‘Soft Boat’, as it became known) was due to be deinstalled, these same fishermen objected with equal vehemence, demonstrating a perfectly Gallic blend of recalcitrance and pride. In response, the commissioning body, Le Voyage à Nantes – a name shared by the city’s tourism agency and by its summer arts festival – negotiated a new contract with the artist. Today the sculpture remains in situ in its out-of-the-way corner, which has nevertheless become part of the tourist trail.

Nantes was once known as ‘the Venice of the West’ – a reference to the many riverine islands on which it was built. All that changed when its channels were infilled during the 1920s and ’30s. This decision lost the city its most picturesque characteristic. As I walk its streets, I can just about guess which roads were once rivulets. In 1943, Allied bombs hit the city centre. By the 1970s, Nantes was a distinctly unglamorous place known for its shipyards, perhaps the Castle of the Dukes of Brittany, and not much else. When the shipyards closed in the ’80s, an exodus of workers caused further decline.

The Castle of the Dukes of Brittany, Nantes. Photo: © Philippe Piron/LVAN

Nowadays, however, tourists flock to a city that boasts attractions ranging from a steampunk menagerie of mechanical animals to the Green Line: a 22km-long line painted on the pavement, connecting some 100 public artworks and historic buildings. And then there is Estuaire, the sculpture trail that has put obscure corners on the map with dramatic additions to the landscape. These include 18 illuminated rings along a city quayside (Les Anneaux, a work of 2007 by Daniel Buren and Patrick Bouchain), which when viewed from one end provide a perspectival trick beloved of Instagrammers. Similarly popular among snappers (and clambering children) is Serpent of the Ocean (2012) by Huang Yong Ping, a 130m-long aluminium skeleton of a snake, situated on a beach at the other end of the trail. Most effective, perhaps, is Maison dans la Loire (2007) by Jean-Luc Courcoult: a scale replica of an inn in the nearby town of Lavau-sur-Loire, half-submerged in a lonely stretch of river. At night, a solitary light can be seen in an upper window. The work is particularly poignant in low-lying Nantes, where flooding provoked that historic infilling of its island channels. (If 1–2m sea level rises predicted by the end of this century come to pass, the work – already sobering – will take on a prophetic aspect.)

Maison dans la Loire (2007), Jean-Luc Courcoult. Photo: © Philippe Piron/LVAN

The regeneration of Nantes began in 1989, when the socialist mayor Jean-Marc Ayrault and the art director Jean Blaise set about transforming its fortunes through free public art events. They started with the annual festival Les Allumées (1990–96), in which artists filled empty spaces in the city from 6pm to 6am for six nights. Blaise was also responsible for creating a new cultural centre, Le Lieu Unique, in a former biscuit factory in 2000; for three editions of a biennial, Estuaire (2007–2012), which has left its mark in the form of the trail; and most recently, for the summer street festival Le Voyage à Nantes. The rewards for such efforts aren’t just cultural. The festival costs €2m to put on; in return, around €60m flows into the city.

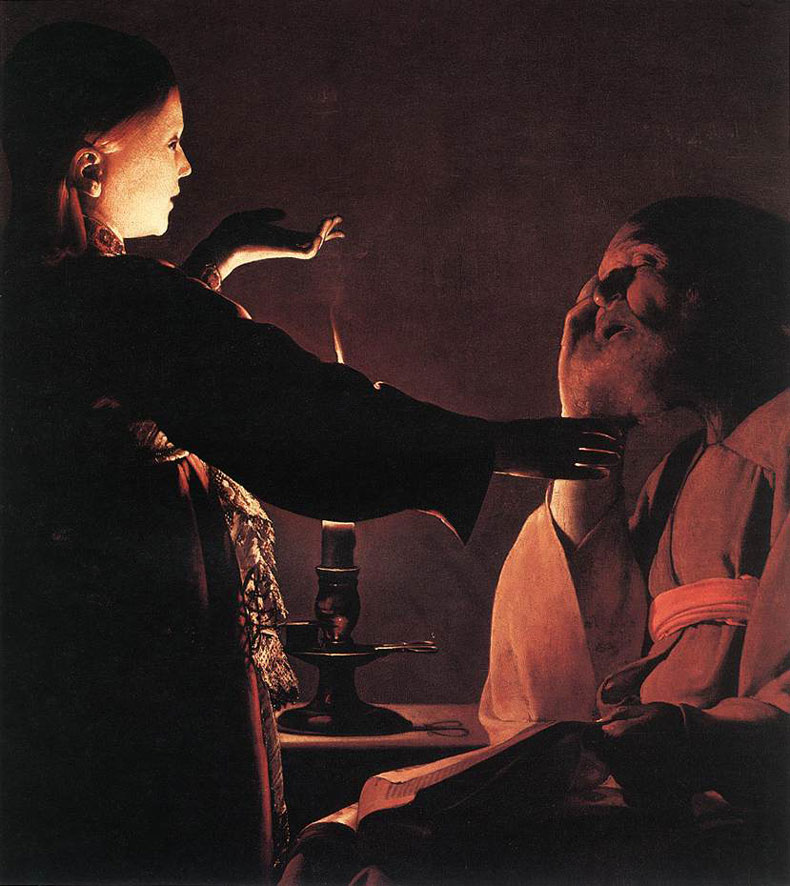

The Dream of Saint Joseph (c. 1628–45), Georges de la Tour. Musée d’Arts de Nantes

Such initiatives coexist with cultural institutions of a much older pedigree. In 1801, Nantes was one of 15 regional cities to benefit from Napoleon’s Decree Chaptal, receiving some 40 paintings from the Louvre (then the Musée Central). The donation formed the basis of the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, today the palatial Musée d’arts de Nantes. In 1810 these holdings were supplemented by a whopping municipal purchase: 1,155 paintings, 64 sculptures and 10,000 prints were bought for the city from the Nantais collectors Pierre and François Cacault. In the decades since, an acquisitions policy focused largely on works by living artists means that the collection has gradually grown to encompass works by Courbet, Ingres, Fantin-Latour and Delaunay. It also boasts transcendently beautiful paintings by Georges de La Tour such as The Dream of Saint Joseph (c. 1628–45), which demonstrates both his sensitivity in depicting candlelight and his skill in rendering human frailty.

That the economy of Nantes today is booming can be attributed, at least in part, to decades of investment in the arts and the subsequent influx of tourists. Inevitably, this success has brought its own problems – Nantes has one of the highest levels of population growth in France with some 10,000 new inhabitants moving to the city each year, putting pressure on its public services and housing market. But all the same, the cultural regeneration of Nantes could serve as a model for other cities that have struggled to find their feet since manufacturing moved abroad.