It is sometimes said that to understand the son, you must look to the father. In the case of Inti Ligabue, the legacy of his father – and his mother – looms large. Giancarlo Ligabue was a maverick. When the Italian journalist Gian Antonio Stella was asked to write an introduction to a book of Ligabue’s writings, he gave it the heading: ‘The Aim of His Life? To Have Two’. Ligabue was not only one of the most successful Italian entrepreneurs of his generation, who transformed the Venetian marine services company he had inherited into a global enterprise, but he was also a palaeontologist, archaeologist, ethnographer and, most notably, explorer.

This is a man who had dinosaurs named for him. Masrasector ligabuei (discovered in Oman in 1989), Cearadactylus ligabuei (Brazil, 1983), and Araripescorpius ligabuei (Brazil, 1983). With the French palaeontologist Philippe Taquet, he discovered in the sands of the Sahara in Niger the near complete skeleton of the 100 million-year-old, seven-metre-long herbivorous Ouranosaurus nigeriensis that is now the star exhibit of the Museo di Storia Naturale in Venice. That expedition of 1972–73 inspired Ligabue to found the Centro Studi Ricerche Ligabue that has, among other activities, sponsored some 140 international expeditions on five continents – many of which he took time out of his day job to join. His occasionally hair-raising adventures led to encounters with remote peoples hitherto unknown to the outside world (the Tau’t Bato of the island of Palawan in the Philippines) and to the last of the Mayan bloodline, and to discoveries of lost cities (Turkmenistan) as well as the material culture of civilisations too numerous to list.

Male figurine (19th/20th century), Congo. Photo: Giancarlo LIgabue Foundation

It may seem as if Indiana Jones had met Marco Polo, but Ligabue’s spirit of adventure was tempered by academic rigour. While Professor Henry Walton Jones Jr was teaching at the fictional Marshall College in Connecticut, Giancarlo Ligabue was studying for a doctorate in palaeontology at the Sorbonne in Paris. The full extent of his curiosity about mankind begins to dawn on me when I visit the family home on the Grand Canal to meet his son. For here, tantalisingly, is a fraction of the 3,500 or so objects that he had acquired and kept (over 2,000 pieces were placed on permanent loan to the Museo di Storia Naturale in the 1990s). It is a collection of which Inti Ligabue is now custodian and champion, and to which he is carefully adding.

It is clear that the son has inherited something of the father’s energy. Arriving late after a day spent at the helm of Ligabue Spa, he bursts into the room full of apologies, but smiling broadly. When I later make some reference to how busy he must be, he laughs and says, ‘If only you knew.’ Now, however, after a quick espresso and a glass of water, he plunges enthusiastically into a tour of the late 15th-century Venetian gothic palazzo and its remarkable and eclectic contents.

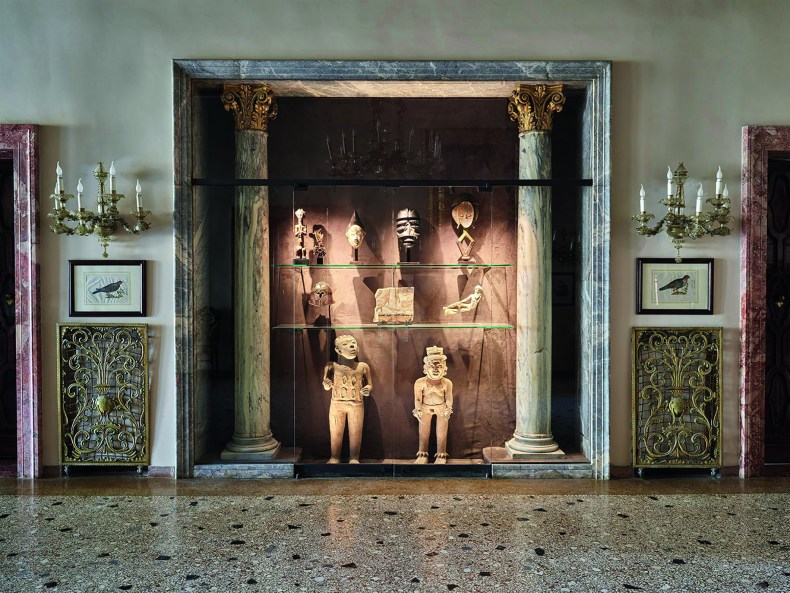

An imposing vitrine in the salone on the piano nobile, for instance, presents 19th- or early 20th-century Fang, Vili/Tombe, Punu, Guere, and Kota sculpture from Africa, with a Corinthian helmet and reclining figure (both from 5th-century BC Magna Graecia), and a 4,000-year-old VI Dynasty fragmentary relief of a fishing scene from Saqqara. Below stand two imposing terracotta figures wrapped in jaguar skins from the Veracruz culture of Mexico, one from the 9th century, the second, earlier. Nearby is an Etruscan bronze shield that was exhibited at the Palazzo Grassi when Fiat used the building as a venue for blockbuster presentations of ancient civilisations – the Celts, Mayans, and Etruscans among them (Giancarlo was on its board).

Vitrine containing 19th/20th-century sculptures from Africa, a Corinthian helmut and reclining figure from Magna Graecia, both 5th century BC, and a relief from Saqqara; below: two Veracruz terracotta figures from Mexico. Photo: James Mollison; © Giancarlo Ligabue Foundation

We pass a monumental Luca Giordano that has just returned from the restorers, and Inti explains that he is gradually conserving all the Old Master paintings. A door opens into a room lined with Old Master drawings, mostly by artists from Venice or the Veneto, and including a joyous wall of pen, ink, and wash caricatures by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. ‘My father liked to draw caricatures too,’ Inti explains, ‘and he particularly loved Giambattista Tiepolo.’

Elsewhere are vitrines of Greek red- and black-figure vases, and Geometric pyxides, Corinthian amphoras, and Mycenaean kylikes, which Inti picks up and turns to reveal the decoration and signature. He has just had new bases made for a row of ancient helmets that now seem to float in space. ‘They look completely different,’ he enthuses. ‘They are alive.’ Nearby hangs a collection of Tuscan and Sienese gold-ground panels, and early Renaissance paintings. Beside them is a model dating to around 1500 of a Venetian galley made for both trade and war fleets, which was built by the shipyards in the Arsenale, one witness to Giancarlo’s evident fascination with maritime history.

Nowhere is his presence more strongly felt, however, than in his retreat of a study in which every wall is lined, every bookcase crammed and each vitrine full of remarkable objects. One contains a spectacular group of small neolithic female idols – Cycladic, Anatolian, Sardinian, Cypriot, Greek, Bactrian, Romanian, Mesopotamian, Maltese… At the centre is the figure known as the ‘Ligabue Venus’ which is, for Inti, the jewel in the crown. It is not clear whether these small but majestic Bactrian statuettes made in contrasting green steatite and cream calcite during the late third and early second century BC are in fact seated princesses or deities, although this figure was found in a grave. Ligabue senior wrote one of the first books on Bactrian antiquities, in 1988.

Female figure (the ‘Ligabue Venus’) (2500–1500BC). Photo: © Giancarlo Ligabue Foundation

It was in this room that Inti remembers rolling the putty for his father to take impressions from the collection of ancient Mesopotamian cylinder seals, revealing images of kings and heroes, myths and battles, and scenes of animals drawn from daily life. ‘You have to realise that there was a 50-year age difference between my father and me, and I did not really know him very well,’ Inti begins, suddenly quiet. ‘When he passed away at the age of 85 in 2015, I was 34, and he had been very ill for a long time and sadly that is mostly how I remember him. While I was growing up he was always away on business, working as an MEP, or else talking on the telephone. The only occasions when I spent any time with him were on his annual expeditions when he would take one or two months off to do what he really loved. It was like meeting a different person. When we landed on Easter Island, for instance, the first thing he did was kiss the ground. I went with him every year for seven years from the age of nine.’ Here Inti grins broadly, remembering his younger self: ‘We went to Australia two consecutive years for two months, looking for Aboriginal paintings. It was fantastic. In the mornings, we would look for big agglomerations of rocks and then land the helicopters and search, and I would fish in the afternoons to feed the team. We found three major paintings. That was another book.’ He continues: ‘My father tried to tell me about the things that we found or he collected but the truth is that I was not very interested then. I would love to have those conversations with him now.’

Giancarlo was fascinated by what he called the ‘Damascene moments’ that changed the world – the birth of writing, the discovery of the Americas – as well as with the origins of life and the essential, unchanging preoccupations of mankind. ‘I never knew whether he collected what he studied or studied what he collected,’ admits Inti, pointing out the interconnectedness of the apparently chaotic collections – and that his father’s acquisitions were made on the international art market and not at source. Giancarlo was committed not only to supporting archaeology, palaeontology and natural science through expeditions and publications, but also to popularising these fields through TV documentaries and the biannual Ligabue Magazine. While he would gladly lend to exhibitions, he never thought of showing his own collection. ‘He studied all his pieces, and he published all his pieces, so it was not about secrecy. Perhaps first-generation collectors are a little more private,’ his son speculates.

In 2014, Inti decided to use the family’s pre-Columbian holdings to tell the story of those cultures that existed in parallel to the West for 2,000 years in ‘The World That Wasn’t There: Pre-Columbian Art in the Ligabue Collection’. His mother, Sylvia Granier Ligabue, was originally from the Tiahuanaco valleys of Bolivia, and named him after the benevolent sun god of the Incas. ‘I feel my South American roots very strongly and I am very proud of them,’ he says. It turned out to be a very emotional project as his father died before the show opened at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Florence the following year. (The dedication to the catalogue reads ‘To Sylvia and Giancarlo, so far, so close.’) This event was perhaps his own Damascene moment. ‘I was used to seeing these pieces dotted around the palazzo in different places and it was a shock to see them all together, sorted into their different cultures from Olmec onwards, and presented in a didactic way. I realised that this was what I had to continue to do.’ To this end, he set up the Fondazione Giancarlo Ligabue.

An even greater shock was the reception of the second show, ‘Before the Alphabet: Journey to Mesopotamia at the Origins of Writing’, at the Istituto Veneto di Scienze, lettere ed Arti in the Palazzo Loredan in Venice earlier this year. ‘We realised we had to be proactive and interactive,’ Inti explains. ‘The Foundation organised everything, including visits from 140 schools with 4,000 kids, and we also encouraged learning by games, such as having the kids write their names in cuneiform on tablet. In 74 days we had 15,000 visitors. It was amazing.’ There was a similar response when the Pre-Columbian show moved to the Museo Archeologico di Napoli, where ‘Before the Alphabet’ is currently on show (until 30 October), and projects with other Italian museums are in the pipeline.

Reliquary figure (19th century), Gabon. Photo: Giancarlo Ligabue Foundation

After his father’s death, Inti tried to get to grips with the collection by digitising the archive. After a month of sitting down every night, often helped by his girlfriend Cristina Tricanato, a busy lawyer, and typing in entries and uploading photographs, they realised they had to hire an archivist. But the exercise served a purpose, for it was by looking closely at what his father collected and going through his father’s notes and his correspondence with the leading authorities of the day, and by reading the bibliography, that he began to understand more about the objects and his father. But there is more than filial piety at work here. ‘Obviously I want to honour my father, but I don’t have to do all this,’ he says. ‘I really believe in what he was trying to do, and I feel there is still a dialogue between him and me with these objects.’

He cites an Ewa wooden sculpture from New Guinea that he had wanted to bid on at auction, but at the time of sale he was flying to Kazakhstan on business. When he discovered that the piece had not sold, he rang up and bought it, and then looked up its provenance. Cross-checking it with his father’s old marked-up auction catalogues he discovered that he had tried to buy it 30 years before.

His own collecting is also wide-ranging, and he is both adding to some of his father’s collections as well as venturing out into new fields, such as photography. ‘Buying archaeological material today is difficult. I will occasionally buy a masterpiece with a long provenance, like the onyx Teotihuacan mask.’ Meanwhile, the Old Master paintings collection has seen dramatic additions of 16th- to 18th-century Venetian paintings, and engravings, but it is the field of tribal art, and African art in particular, that has come to engage him.

‘This was never a major interest of my father’s and, with the exception of a Dan mask and a Mende mask, all his tribal pieces are Oceanic, no doubt because of his interest in navigation.’ We are now in a very contemporary sitting room, admiring not only sublime ceremonial paddles and steering poles but also groups of clubs, sticks, spears and battle hammers. ‘It fascinates me how these power tools have an aesthetic not only of force but also of grace’, he says: ‘Look at that fantastic Sali war club from Fiji, it is in the shape of a banano flower’. The elegance of a duck-beaked battle hammer with a studded pineapple-shaped knop belies its ferocity as a weapon.

Here, too, is a group of large ceremonial spoons. These anthropomorphic masterpieces are more sculptures than utensils, and were awarded to the most hospitable woman in a Dan village, the we ke de, who was responsible for welcoming and celebrating the masquerade spirits. Unlike his father, Inti is more interested in the aesthetics of a piece than its ‘scientific’ value, and in terms of African art is more attracted to these kinds of abstract forms than to the classical and, unlike Cristina, to ‘strong pieces like fetishes’.

His first purchase, however, was a classic Punu anthropomorphic mask painted with kaolin and other natural pigments. It is currently on show – as are many pieces from the collection – in ‘Intuition’, an exhibition curated by Axel Vervoordt and Daniela Ferretti at the Palazzo Fortuny in Venice until 26 November. He had gone to Paris in pursuit of a Kota figure, walked in to the gallery and was dazzled. ‘I had that shaky, sweaty thing that you have when you see a major piece. I knew I had to have it. It was an impulse purchase but afterwards I came to realise its importance.’ He later bought the Kota piece, too – a characteristic reliquary guardian figure or mbulu ngulu – and added several striking power figures.

‘Art is where human beings express their fears, beliefs and their way of life,’ Inti concludes. ‘Collecting is about being curious about humanity, and about giving a voice to “lost” cultures. The responsibility of the collector is to be the narrator and poet of these objects, and also to share this culture. This is what I really learnt from my father.’

From the July/August issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.