From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Last month’s memorials to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki underlined how few people now have first-hand memories of the Second World War. So it is all the more remarkable, 80 years after it ended, that the war still casts such a long shadow over museums and the art market.

In March, the Tate announced that it would return a picture by the 17th-century English painter Henry Gibbs to the great-grandchildren of Belgian-Jewish art dealer Samuel Hartveld. It bought Aeneas and his Family Fleeing Burning Troy (1654) from Galerie Jan de Maere in Brussels in 1994 and displayed it in what is now Tate Britain. But research last year established that it had been among the property seized by the Nazis after Hartveld fled from Antwerp to New York in May 1940.

The Tate is not alone. The Art Institute of Chicago, the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid and the Kunstmuseum Basel are among the many museums recently embroiled in restitution claims. Cases involving private collectors are also increasing. The Art Loss Register, which oversees a database of lost and stolen art, estimates that 15 per cent of its 700,000 works are Nazi loot. ‘There is no doubt that Holocaust-era claims are on the rise,’ says Rudy Capildeo, joint head of art and luxury at London law firm Wedlake Bell. ‘We have several cases, acting for innocent purchasers, for nation states and museums, and for claimants who want to get their objects back.’

In the United States, despite the deep divisions between the Republicans and Democrats, a cross-party group of senators is steering the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery (HEAR) Act Improvements of 2025 through Congress. It is far from a straightforward update of the 2016 act of the same name. It will sweep away several procedural safety nets that have protected owners and, some say, will put claimants in the driving seat.

Few expected this in 1998 when the US State Department invited museum directors, auctioneers and government officials from 44 countries to the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., to discuss Nazi-confiscated art. They agreed a set of 11 principles to help countries root out stolen works and resolve their ownership.

Many believed that the problem – that the Nazis had systematically taken art from mostly Jewish art collectors and dealers, storing or selling it on the open market – would soon be resolved. But the conference reached no binding agreement and as museums researched their collections and descendants became emboldened, the number of claims rose. One of the best known, thanks to the film The Woman in Gold (2015), was the fight by Maria Altmann, last surviving heir of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, to secure the return of five paintings by Gustav Klimt. These, including the famous portrait of her aunt, were hanging in the Belvedere Museum in Vienna with a label incorrectly claiming they had been bequeathed by the family.

Norman Rosenthal, former exhibitions secretary of the Royal Academy, wrote in 2008 that ‘the time has come for a statute of limitations on restitution’, arguing ‘the process has been ongoing for 10 years, and the items in question have often been claimed by people distanced by two or more generations from their original owners’. A few years later Klaus Schröder, director of the Albertina Museum in Vienna from 1999–2024, suggested that a line should be drawn in 2045, repeating his view as recently as last year.

Congress first introduced a HEAR act in 2016 to solve the problem of individual US states having different statutes of limitation. Claims had been dismissed simply on the basis that it was too late for courts to hear them.

The HEAR act gave claimants six years from ‘actual discovery’ – the point when descendants became aware of both the location of an artwork and their right to claim it. It also swept away a defence known as ‘constructive discovery’. This allowed an owner to argue that because a painting had been published in an auction catalogue, for example, that the claimants ought to have known its whereabouts many years before.

The updated act goes further. According to Jonathan Freiman, a partner at US law firm Wiggin and Dana, it sets aside the doctrine of laches. This is a concept derived from an old French term meaning ‘an unreasonable delay’ and is used to argue that a defendant cannot get a fair hearing because the years have degraded crucial evidence. ‘This sounds technical, but it is central to justice,’ Freiman says. ‘The passage of time can prejudice defendants because access to truth fades: witnesses die, documents disappear and all that is left are second-hand stories.’

He is also concerned that the new act would allow claimants to sue foreign ‘sovereigns’ – including public museums – in the United States if they believe they have Nazi-looted art in their collections. This happened in the Altmann case but has been subsequently overturned by the Supreme Court. ‘International law doesn’t allow this,’ Freiman says. ‘It requires nations to give foreign sovereigns immunity from being sued for sovereign acts. The sponsors of the new bill are wrong to flout international law and are risking [unforeseen] international conflicts.’

This is even more problematic, Freiman says, because ‘in the US, most of the classic Nazi-looted art situations – that work was pulled off a wall or they forced someone to sell for a fraction of its value – are mostly over and done with. Reputable museums, dealers and collectors in the US now restitute work when they find evidence, so the cases that are coming up today tend to be weaker.’

Others disagree, arguing that although many of these legal technicalities are important, the balance has swung too far away from righting Nazi wrongs. ‘The historical record shows that Nazi era claims are extremely difficult to bring,’ says Nicholas O’Donnell, a partner at US firm Sullivan & Worcester. ‘Most Nazi era art that was taken is not high value and is economically very difficult [to prosecute in law].’

O’Donnell and Freiman were both involved in the Guelph Treasure case in the Supreme Court in 2021, a long-running battle between the heirs of four German Jewish art dealers and the Museum of Applied Arts in Berlin, owned by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. Isaak Rosenbaum, Saemy Rosenberg, Julius Falk Goldschmidt and Zacharias Max Hackenbroch bought an outstanding group of medieval objects in 1929. Over the next few years they sold 40 of the pieces, mostly in the United States. The case revolved around the other 44 sold in 1935 to the State of Prussia, then governed by Hermann Göring. The works, with an estimated value of $250m, are now in the Berlin museum.

Freiman, representing the foundation, argued that the 1935 sale was not forced and although it was sold for less than the dealers paid in 1929, this was a result of the collapse in value during the Great Depression. The heirs, represented by O’Donnell, disagreed. But the case in court revolved around the interpretation of the US Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA).

The court eventually decided that it did not have jurisdiction. O’Donnell believes that this contradicts Congress’s original intentions when it introduced the FSIA in 1976. ‘The idea that Congress didn’t want German Jews protected from Nazi theft is not what the statutes say. So this would correct that and say: “no, Supreme Court, try again for jurisdictional purpose when it comes to Nazi-era stealing of art”. That’s one of the key parts of this new bill.’

If it is passed, the bill could affect other cases. One of the most contentious concerns Camille Pissarro’s Rue Saint–Honoré, après-midi, effet de pluie (1897), now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. It was sold by Lilly Cassirer Neubauer, a member of a prominent family of publishers and art dealers, for less than its market value to escape Germany in 1939. The painting was bought in 1976 by Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza: in 1993, his collection was bought by the Spanish state. Lilly Cassirer’s family made their first claim on the painting in 2002, and it has been fought through the US courts since.

The HEAR act will affect museums but possibly the art market too. The World Jewish Restitution Organisation estimates that at least 100,000 works of art and millions of books and religious items are still missing. Last year it criticised the ‘lack of progress on items currently in private hands’ and called for Congress to enact the 2025 HEAR act as swiftly as possible.

The major auction houses introduced restitution departments at the end of the 1990s. Christie’s now has seven researchers focused on the Nazi era, making sure fine and decorative art objects offered for sale have a clean bill of health. ‘When I started this work [at Sotheby’s] in 2006, I wondered if there would be anything to do by 2016,’ says Richard Aronowitz, global head of restitution at Christie’s. ‘But now I don’t think it will be finished in my lifetime.’

One reason Aronowitz gives for the rising number of claims is that the amount of information is growing as countries open up their archives and digitise records. ‘When I first started there were two or three main sources of information, but now there are at least 10 separate datasets which my team need to know how to check,’ he says. The understanding of what constitutes loot is also changing. ‘The Washington Principles talked about Nazi-confiscated art. The definition of that has broadened vastly in the past 27 years,’ he says. ‘Now we are looking for all kinds of losses, from forced sales to sales under duress and so-called flight assets.’

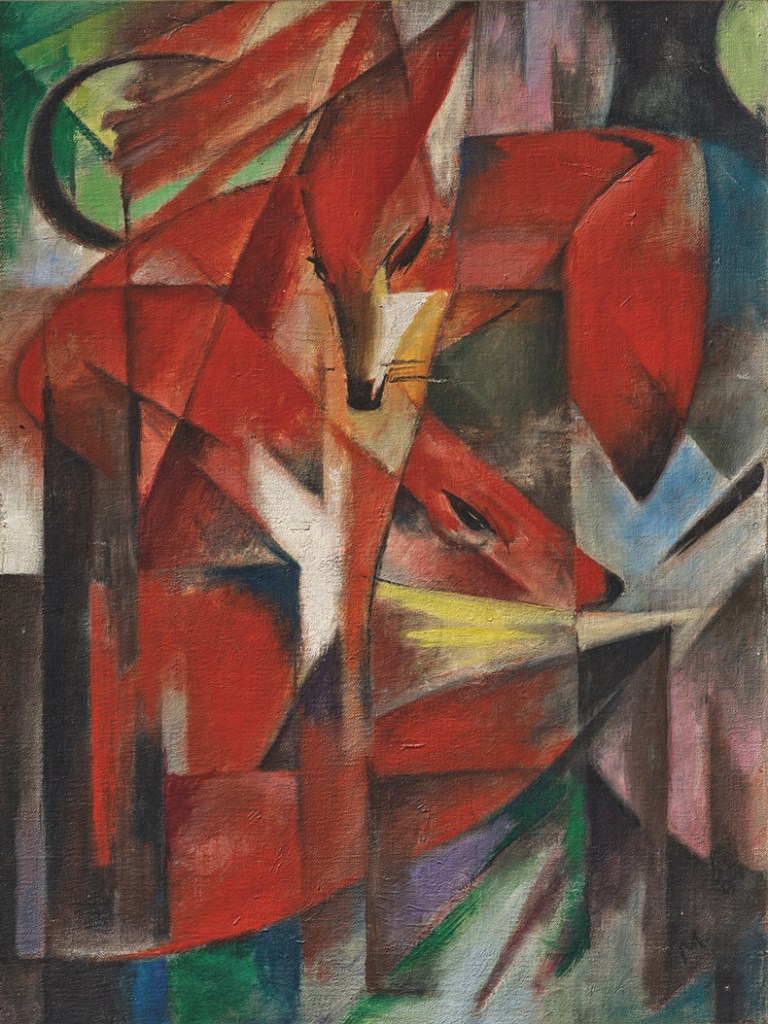

In 2021, the City of Düsseldorf returned Franz Marc’s Die Füchse (1913), which it had received as a donation in 1962, to the heirs of Jewish banker Kurt Grawi. He bought the picture in 1928. By 1935 his business had been seized and in 1938 he was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen for several weeks. In 1939, Grawi escaped Germany, smuggling the painting out and selling it for an unknown price in New York in 1940. ‘That was a seismic moment in this field,’ says Aronowitz. ‘It is one of the first times a restitution committee has recommended returning a work not sold in Nazi Europe but in New York.’

It is more common for auction houses to negotiate a division of proceeds between a private owner and a claimant when a work is sold, rather than ending up in court. Nevertheless, Aronowitz welcomes the revised HEAR act. ‘There are obstacles in the US to taking claims to court – the passage of time, laches and statutes of limitation that make it nigh on impossible. The US was the key drafter of the Washington Principles, so it is good it is bringing a bill designed to address these issues.’

Others say that the art market is already well ahead of the law. ‘Regardless of the legal position, a work of art is unsaleable if it is perceived to be “tainted,”’ says Julian Radcliffe, founder of the Art Loss Register. ‘Nobody wants to be associated with it – it’s a reputational issue and that factor is almost as important as the first.’

Meanwhile, the whole field of provenance is changing rapidly. In the early 2000s, art stolen during the Holocaust was seen as a single, uniquely dreadful exception to regular rules of ownership. But as the years have gone on, awkward questions are being asked about the way many more kinds of art – colonial-era art, ethnography and work made by Indigenous peoples particularly – have made their way into private collections and museums. Later this month, the French Senate will vote on a bill to allow national museums to deaccession items plundered from former colonies.

‘In the past, people went to museums to appreciate the art. Now, one of the first questions we are asked, especially by younger people, is how things got here,’ says Jacques Schuhmacher, executive director of provenance research at the Art Institute of Chicago. ‘It is a change that’s happened as museums have become places where societal issues are debated.’

Establishing provenance and ownership means time, money and expertise – a great deal of it. Far from fading away, who owns what – legally and morally – has become one of the art world’s knottiest problems.

From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.