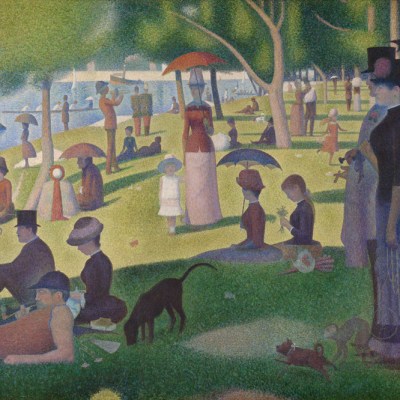

How fitting that the National Gallery should launch its new temporary exhibition galleries in the Sainsbury Wing by unveiling works of art never or only rarely seen in Britain and a style of painting relatively little known. Neo-Impressionism, a term coined by the critic Félix Fénéon but perhaps better known as pointillism or divisionism, was launched on to the Parisian art scene in 1886, when Georges Seurat exhibited his monumental A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884 (1884–86) at the eighth – and final – Impressionist exhibition. Camille Pissarro described the movement it engendered as ‘a new phase in the logical march of Impressionism’. Driving this new phase was the science of optics and colour theory.

As the chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul had found earlier in the century, pairings of contrasting complementary colours – blue and orange, red and green, purple and yellow – acquired ‘the most remarkable brilliance, strength and purity’. More recently, Charles Blanc, Ogden Nicholas Rood and Charles Henry understood that greater luminosity could be achieved by ‘optical mixing’, the juxtaposition of two pure colours which would be perceived as a third at a distance. Seurat’s experimentation in dividing his colours on the canvas led to their ultimate reduction into a dab or dot and an ‘optical fusion’ that gave his paintings an intensity of light and a shimmering surface. For Fénéon, the Neo-Impressionists created the very ‘sensation of life itself’ and a ‘higher reality’.

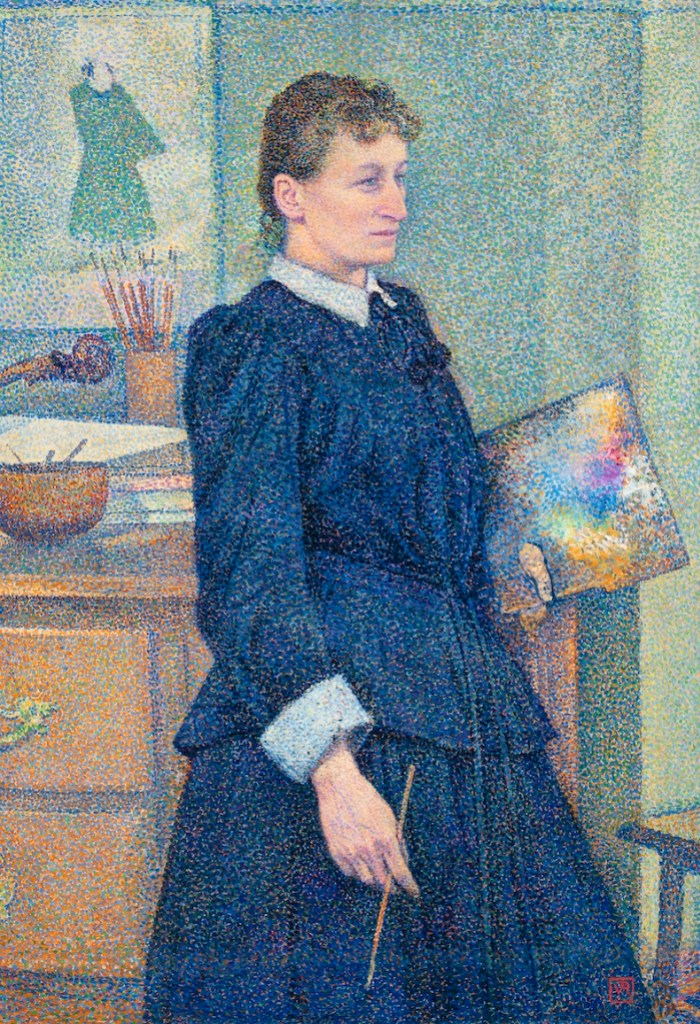

What this show emphasises from the outset is that the Neo-Impressionists were not all French and did not all live and work in Paris. Most of its leading lights are introduced in the first two galleries: Seurat, Paul Signac, Pissarro and Maximilien Luce, the Belgians Théo van Rysselberghe, Anna Boch, Georges Lemmen and the artist-turned-architect Henry van der Velde and the Dutchman Jan Toorop. Also introduced is the German-born Helene Kröller-Müller (1869–1939), the wealthy and prescient collector based in Holland who amassed not only the largest collection of the work of Vincent Van Gogh outside the artist’s family – some 90 paintings and 180 drawings – but also, among many other things, a uniquely comprehensive group of Neo-Impressionist works. Her collection, along with her estate in Otterlo, some 80km from Amsterdam, were donated to the Dutch people in 1935 on condition that a museum would be built. Some 42 paintings and works on paper have been loaned by the Kröller-Müller Museum for this exhibition, supplemented by pieces from the National Gallery’s own collection and from other institutional and private lenders.

The degree of ‘otherness’ of Neo-Impressionism is eloquently expressed in the opening sequence of coolly impersonal but strangely poetic port scenes. Signac’s Portrieux, the Lighthouse, Opus 183 and Seurat’s Port-en-Bessin, a Sunday (both 1888), so evocative of the quality of light over water, reveal how surprisingly well suited the small, circular dot was to austere, analytic geometries, the painted dark, inner border of the latter emphasising the pictorial artifice and formal rigour of the work. It is easy to understand why this mechanistic application of paint, devoid of any expression of individuality in the brushwork, was decried as the end of painting. Yet it is evident that these Neo-Impressionists were as much preoccupied with colour relationships and patterns as pure perception. Signac, as his titles suggest, was fascinated by the relationship between line, colour and musical harmony.

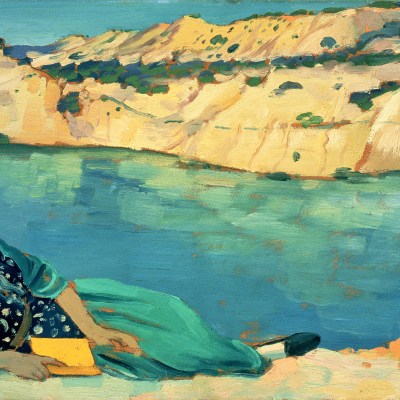

Van Rysselberghe’s ‘Per-Kiridy’ at High Tide (1889) is a revelation. It was painted in response to Seurat’s noble craggy rock, Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp (1885; on loan here from Tate) which had been shown with the progressive Brussels exhibition society Les XX (The Twenty) in 1887. A committed convert to Seurat’s technique after seeing the Grand Jatte at the Impressionist exhibition the previous year, Van Rysselberghe was responsible, along with Van der Velde, Lemmen, Boch, Willy Finch and others, for importing the style to Belgium. Toorop, in turn, introduced Les XX and its invitees to the Netherlands.

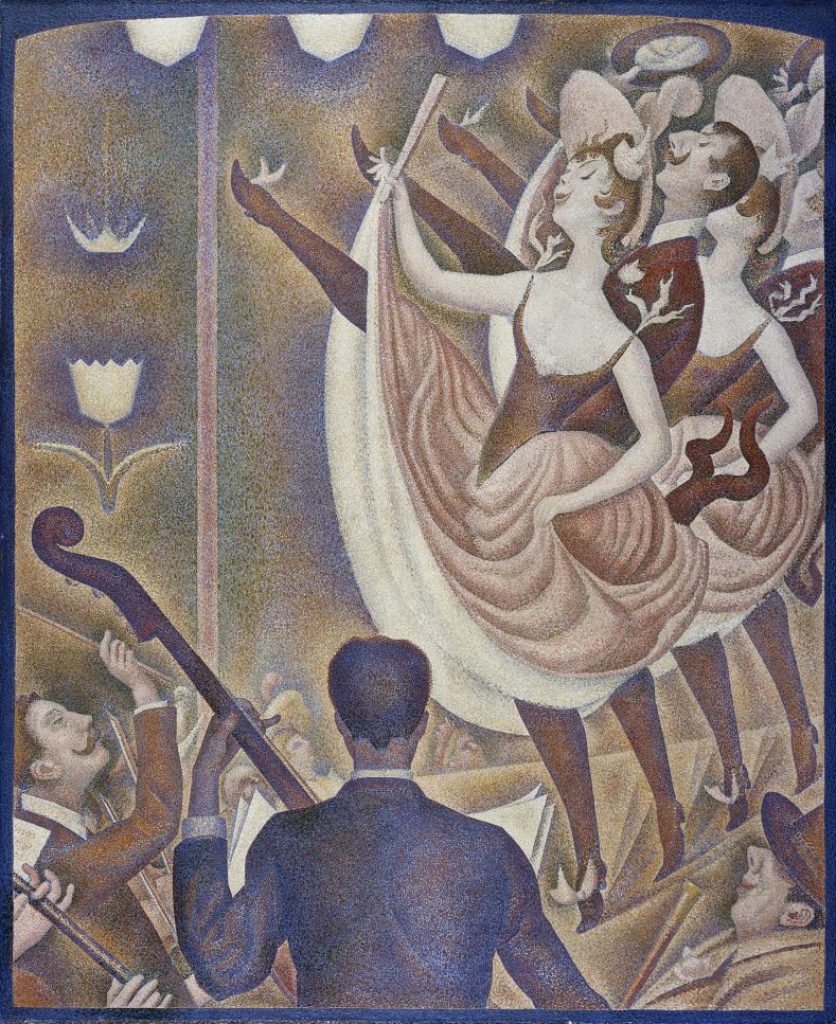

Kröller-Müller was advised not to buy A Sunday on La Grande Jatte. She did, however, acquire the artist’s remarkable Le Chahut of 1889–90 and considered it the centrepiece of her collection. This was one of Seurat’s toiles de luttes (‘battle canvases’), his most ambitious and provocative manifesto pictures. The provocation of this much-analysed image was not so much the indecent high-kicking can-can and its low-life audience at the cafe concert – note the grubby expectation of the figure bottom right – but rather a new theory of the rising line. The repeating upward diagonals of legs and pointed toes, the upward curves of lip, eye, moustache and wall-light, along with the rhythmically recurring lines and folds of skirt, were intended to produce an effect of gaiety.

Signac, an anarchist, emphasised the political significance of Le Chahut. His radical politics were shared by many in this loosely affiliated group. Toorop knew of the inhumane conditions in the mines of Charleroi in southern Belgium and the violent suppression of strikes. The dread of his shoeless miner in Evening (before the Strike) (c. 1888–89) is proven justified in the pietà-like Morning (after the Strike) (c. 1888–90), in which the worker’s limp dead body is carried away by his family. Van Rysselberghe and Van der Velde had invited Maximilien Luce to visit the region’s mines and foundries, but Luce chose to focus on an alternative anarchist view, employing the scale of history painting to glorify the heroics of unity and co-operation in labour in the high-key The Iron Foundry (1899). His Morning, Interior (1890) is a paean to the dignity of the artisan. Toorop and Van Gogh shared an admiration for Jean-François Millet, and the sympathy and presence of the latter likewise looms large in images of rural isolation and hardship. Moreover, Anna Boch – the subject of a marvellous portrait here by Van Rysselberghe from c. 1892 – is believed to be the only person who purchased a work by Van Gogh in his lifetime.

A sense of isolation, even social alienation, pervades so many of these canvases, even – or perhaps especially – the portraits and multi-figure interiors of bourgeois domestic life. It was a mood previously explored by Gustave Caillebotte, whose influence is especially apparent in Signac’s The Dining Room, Opus 152 (1886–87). This stilted family breakfast scene prompted one Belgian critic to quip, ‘After the Grand Jatte [large bowl] of Seurat, the Petite Tasse [little cup] of Signac.’ As this sequence of portraits and interiors demonstrates, Neo-Impressionism was far from restricted to landscape painting, or even to a single technique.

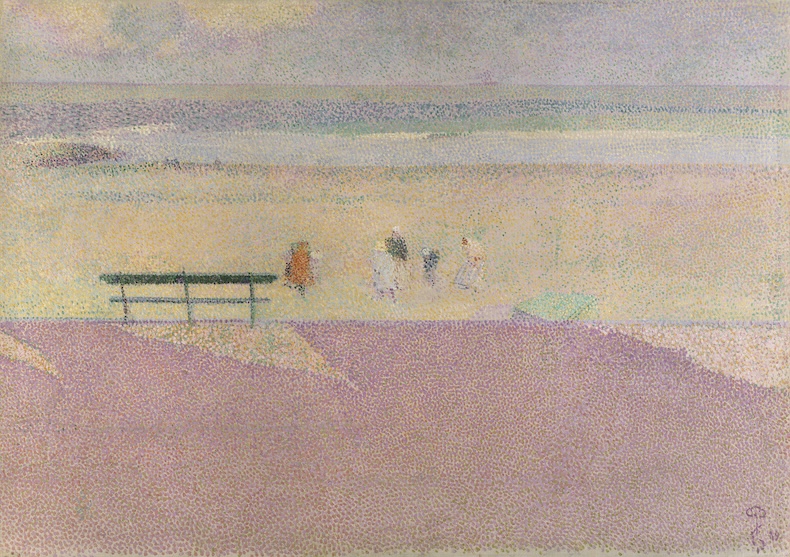

The spareness, stillness and silence of the Neo-Impressionist seascape appear to have been particularly valued by Kröller-Müller. She described these paintings as ‘light and delicate, spiritual in content’ and in stark contrast to her works by Van Gogh, which were ‘dramatic and heavy, like hammer blows’. She saw in Seurat a transcendental quality that is apparent in the of dusk depicted in The Channel at Gravelines, an Evening (1890) and in the no less contemplative visual emptiness of Van der Velde’s Seashore (The Beach at Blankenberghe) (1889). In a sense, these avant-garde paintings both marked the swansong of the old century and heralded the new.

‘Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists’ is at the National Gallery, London, until 8 February 2026.