‘People used to ask for Soho red,’ says Denise Mitchell. In the 20th century, Soho in central London was synonymous with sex, and therefore with the scarlet light of neon. Strip joints like the Windmill Theatre, which sidestepped strict obscenity rules by showing their nude women in motionless tableaux vivants, had their names and functions spelled out in giant neon letters, giving the neighbourhood a characteristic blood-red glow. On the Raymond Revuebar sign in Walker’s Court, a cancan dancer kicked her legs, animated by different tubes being lit up in alternation. Smaller, seedier venues had signs that simply said ‘GIRLS GIRLS GIRLS’, or showed a heart with a keyhole, signifying a peep show.

Mitchell has run the Neon Sign Store in east London with her husband Chris for more than 30 years – Chris bends the glass tubes that are the conduits of neon light in his workshop, and Denise deals with the customers. ‘When we started it was all clubs and sex shops, now it’s all art and home decoration,’ Denise says. As Soho has been sanitised and gentrified, its neon has become rose-tinted, so to speak – a quirky accessory for the living room. When Chris is summoned to Soho today, it is to repair the few old signs – such as the Windmill’s – deemed worthy of preservation.

The red of Soho is the natural colour of neon light. But neon itself is invisible – and in every breath we take. It’s one of the inert ‘noble’ gases that comprise a tiny fraction of the Earth’s atmosphere, alongside the likes of argon, krypton and xenon. The British chemists William Ramsay and Morris Travers identified and isolated neon (‘new’) gas in June 1898, filling a glass tube with it and running through it an electrical current to reveal its spectrum. As Christoph Ribbat relates in Flickering Light: A History of Neon (2013), the men were astounded when the tube glowed with ‘a blaze of crimson’. After pausing a while to admire this unexpected property of the gas, they noted its ‘magnificent spectrum’, and moved on.

The gas was harnessed for neon lighting more than a decade later by the Parisian chemist Georges Claude, who established which gauge of tube produced the most intense light and solved the technical problems that impeded commercial application. Claude also experimented with the colours produced by other noble gases – blue-purple from argon, for instance, and a paler blue from xenon.

Claude’s tube was first demonstrated to the public at Luna Park, the Paris amusement park that would become so popular with the Surrealists, in 1911. The first commercial sign using neon lights was installed on a barber’s shop on the Boulevard Montmartre in 1912, and the first rooftop advertisement – for Cinzano – appeared the following year. Though many contemporary critics despised the new light for its vulgarity, it boomed throughout the 1920s and ’30s, its first and truest golden age. But after the Second World War, its image darkened.

‘Neon simply promised too much,’ Sandy Isenstadt writes in the essay ‘Los Angeles After Dark’. ‘Its unwavering midnight optimism turned out to be just another fixed-grin sales pitch for cheap merchandise.’ Furthermore, it shone brightest at night. Neon might have been broadly adopted – Ribbat notes that by the end of the 1920s more than 60 American churches advertised themselves by means of neon crosses – but it quickly became associated with nighttime businesses and urban vice.

Paradoxically, for all its association with the machine age and impersonal modernity, neon tubes are and always have been craft objects. Their appeal lies in the limitless complex shapes that they can adopt, but those shapes are painstakingly handmade with flame and eye – the skills of Murano in the service of Times Square. Ribbat relates that in the 1930s around 5,000 glass blowers were making neon advertisements in the US. But once made, a neon sign can’t be adapted. As advertising and signage technology moved on, neon signs became associated with rundown bars, hotels and businesses that couldn’t update their displays.

From the 1940s on, the neon sign became a staple of noir and depictions of urban sleaze and violence. The essayist Joachim Kalka points out that neon is peculiarly associated with rain, just as gaslight is with fog. It features routinely in the photographs of Weegee (Arthur Fellig), both as the backdrop to crime scenes and as the main event. Billy Wilder’s film The Lost Weekend (1945) uses a drifting parade of neon signs to represent the sad final weeks of an alcoholic’s decline – a scene emulated and parodied dozens of times over. Philip Marlowe, Raymond Chandler’s archetypal hard-boiled detective, says in the novel The Little Sister (1949): ‘There ought to be a monument to the man who invented neon lights. Fifteen storeys high, solid marble. There’s a boy who really made something out of nothing.’

Neon flickers with multiple paradoxes: modern yet run-down, impersonal yet handmade, bright yet melancholy. It promises, as Isenstadt and Chandler both observe, but it does not deliver. It is suggestive of bodily pleasure, but is untouchable and brittle. It is both warm and cold. It may have an affinity with rain, reflections and empty streets, but Isenstadt mentions its suitability to the desert, where colours seem washed out during the day, and a city can come alive at night. This latter quality can be inferred from Every Building on the Sunset Strip, Ed Ruscha’s 1966 photomontage, which includes unlit neon signs in its deadpan appreciation of the everydayness of a major Los Angeles commercial artery in the daytime.

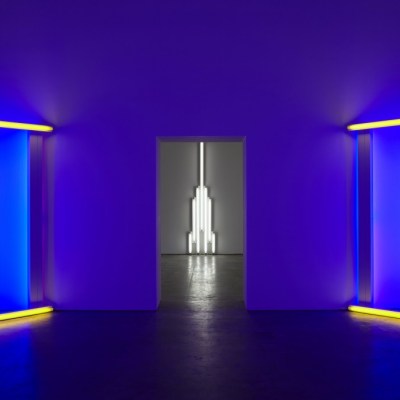

But besides being part of quotidian space, neon can be used to reshape space, making it a draw for installation artists. Dan Flavin explored the monumental properties of neon from the 1960s onwards, just as Lucio Fontana, best known for his slashed canvases, was making a series of giant suspended neon swirls. Today it forms the basis of installations made by artists including Alex Da Corte and Iván Navarro. The seminal neon artist, however, is surely Bruce Nauman, who began making wall-mounted neon text pieces in the 1960s, followed by large-scale installations, and culminating in the ’80s with witty, racy figures that emulated kinetic advertising such as the Raymond Revuebar sign.

Marching Man (1985), Bruce Nauman. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Photo: Bridgeman Images; © Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London 2020

Neon lighting’s linearity makes it particularly well suited to cursive text – Arabic calligraphy works especially well, according to Denise Mitchell. Neon fixes the throwaway word so that it blazes and hypnotises – a fundamental part of its magic is the electric transcendence it brings to a humble announcement like EAT or OPEN. Little wonder it has been irresistible to artists such as Joseph Kosuth and, notably, Tracey Emin, who has been making neon scrawls since the 1990s, holding up the inner emotional voice as valuable and beautiful. The slight sleaziness of neon has always been a slippery part of its appeal, especially on a sterile gallery wall; for Emin the connection with sex and the commodification of the female body is not accidental.

Neon is once more under technological threat. ‘Flex neon’, comprising coloured LEDs in bendy plastic, can replicate the appearance of neon tubing in an unlimited array of colours, and can be shaped by unskilled hands. Like any craft skill, the making of traditional glass neon is kept alive by each generation training the next, and the fabricators are disappearing. Fortunately, denuded of its seediness by artistic reclamation and transit through the retro and the kitsch, neon has become an object of affection. Meanwhile there have been serious worldwide efforts to save and restore vintage examples. Los Angeles has had a Museum of Neon Art since 1981, preserving unique examples of the city’s neon heritage. But the medium’s Louvre is the Neon Museum in Las Vegas, which opened in 1996, just as the city was imploding the last traces of its seedy, glitzy midcentury heyday to make way for corporate resorts. Many of its exhibits are kept in the so-called ‘boneyard’, an atmospheric couple of acres of open ground in which the giant signs of deceased casinos loom like acid-hued moai.

In London, the Raymond Revuebar sign in Soho was restored (by the descendants of Dick Bracey, who made the original in the 1950s) and reinstalled in 2014, ensuring its survival even if it no longer marks the ‘world centre of erotic entertainment’. And fabricators stay in business thanks to the demand for unique pieces of home decor – neon’s very inflexibility gives it an edge over LED replacements if you want to make a special statement. This change in market has its compensations. ‘No more up ladders doing signs in clubs at night,’ says Denise Mitchell. ‘It’s all in people’s homes with cups of tea.’

From the March 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.