It would be reassuring if the posthumous reputations of artists were determined on the basis of pure merit, but there are too many cases of forgotten figures being rediscovered after centuries of hibernation for such a notion to be taken seriously. It is worth admitting at the outset that Carlo Portelli – who certainly deserves to be much better known, and thanks to this exemplary exhibition now will be – is by no means a slumbering giant of the stature of artists such as Vermeer or Georges de La Tour. Yet what makes his case so intriguing is the way in which three distinct but not necessarily unrelated strokes of bad luck across the centuries sealed his fate.

The first was that Portelli merited only the briefest of mentions in the second and definitive edition of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, which was published in 1568, when Portelli – whose date of birth is unknown, but who died at an advanced age in 1574 – was nearing the end of his career. All Vasari has to say about him in the concluding paragraph of his biography of Ridolfo Ghirlandaio is: ‘A disciple of Ridolfo, also, was Carlo Portelli of Loro in the Valdarno di Sopra, by whose hand are some altarpieces and innumerable pictures in Florence; as in Santa Maria Maggiore, in Santa Felicita, in the Nunnery of Monticelli, and at Cestello, the altarpiece of the Chapel of the Baldesi on the right hand of the entrance into the church, wherein is the Martyrdom of Saint Romolo, Bishop of Fiesole.’

Allegory of the Immaculate Conception (1566), Carlo Portelli. Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia

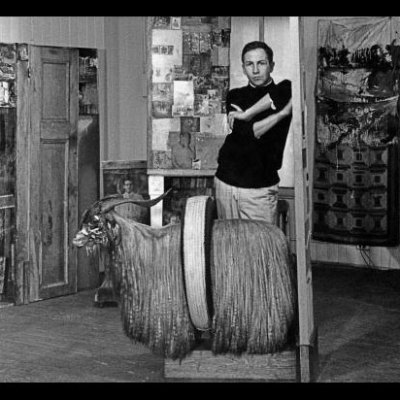

As if that were not a bad enough start, it was followed in 1584 by Raffaello Borghini’s post-Tridentine denunciation in his Riposo of Portelli’s Immaculate Conception for the church of Ognissanti in Florence, above all for its inclusion – in the person of Eve – of ‘a great ugly female showing all of her backside and filling half the painting’. As the work in question has ended up at the Accademia – and is in a sense the raison d’être around which the exhibition has been constructed – visitors are able to judge for themselves, not least since a subsequent cover-up of the offending back view was removed when the work was restored in 2003; many may be surprised to discover that her buttocks were never actually on display. Perhaps as a result of the distinctly bumpy ride Portelli received in the 16th century, he was excluded from both Bernard Berenson’s Florentine Pictures of the Renaissance and The Drawings of the Florentine Painters, and has only relatively recently attracted sustained attention even from specialists on 16th-century Florence.

Restitution of the Cross (1569), Carlo Portelli. Borgo San Lorenzo (Florence), Olmi, church of Santa Maria

At the Accademia, the organisers of this revelatory show have assembled almost all of Portelli’s surviving works – the catalogue includes and illustrates a mere 11 absentees in an appendix. Of these, the only ones of real note are a fine Portrait of a Bearded Man in Wiesbaden, for which the loan request was refused; the Martyrdom of Saint Romulus in its splendid original carved and gilded wooden frame, a short walk away in Santa Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi (as Cestello is now called); and a second Immaculate Conception at Santa Croce, which is currently being restored. After a small introductory space, which features various archival documents alongside a number of paintings and drawings by Portelli, the two principal corridor-like rooms are respectively given over to the artist’s smaller-scale religious works, portraits, and allegories to the right, and six monumental altarpieces to the left. A very select number of paintings and drawings by other artists such as Vasari and Francesco Salviati are also included for purposes of comparison, above all in connection with questions of iconography.

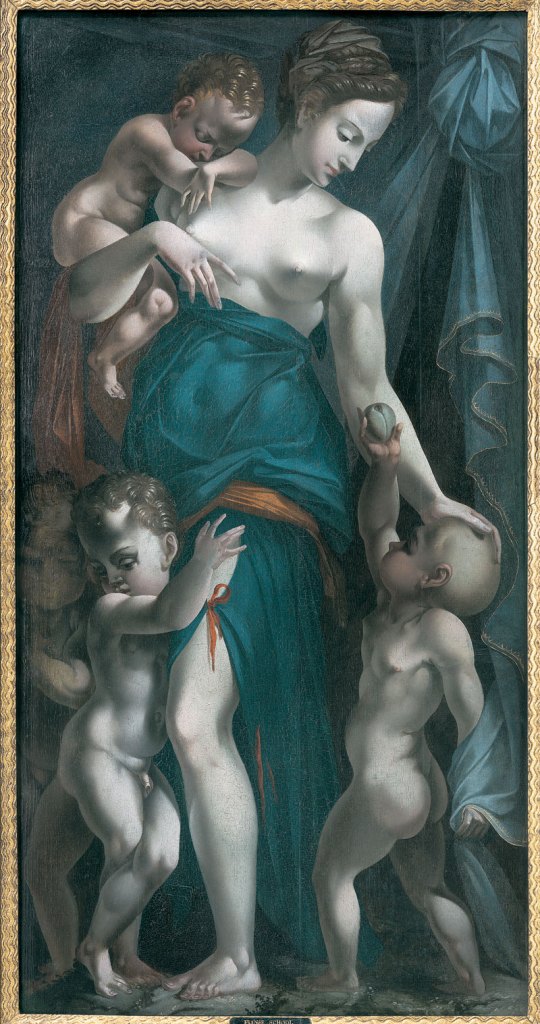

Charity (1555–60), Carlo Portelli. Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht

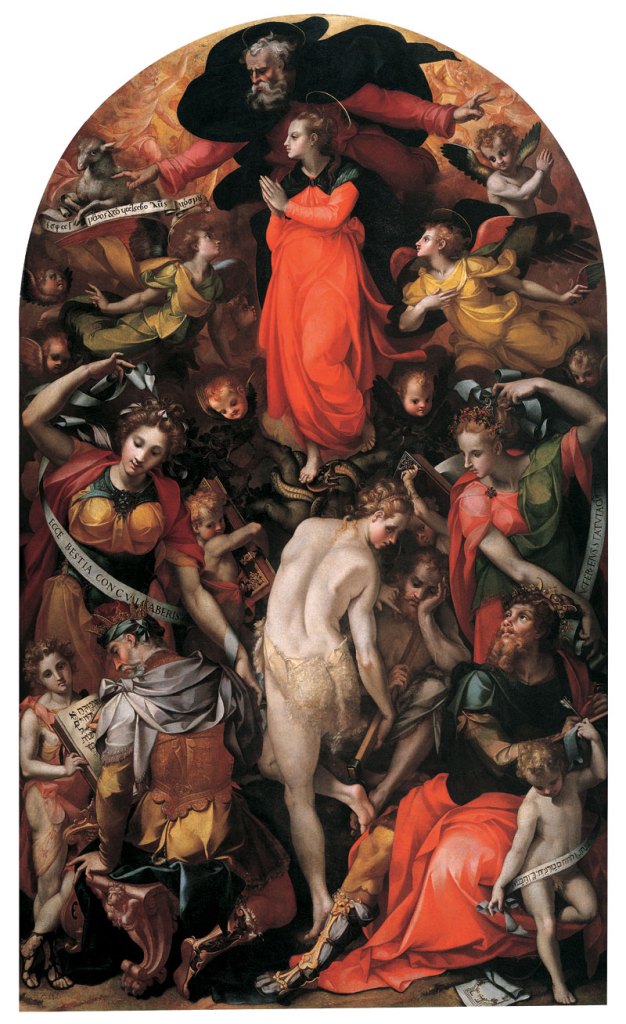

The catalogue is a considerable work of scholarship, and contains a great deal of new research on the artist, both in six introductory essays and in the individual entries. The reconstruction of Portelli’s career that it presents, in terms of attribution and chronology, seems wholly sound, although I have to admit I struggled to see why a fascinating panel representing Charity from the Bonnefantenmuseum in Maastricht had to be by him. The catalogue’s sins of omission are equally few and far between, although it is worth noting – especially given the general tendency to see Portelli as an artist of limited horizons, who scarcely looks beyond Florence and its environs – that an attendant figure with his hands raised above his head in the Martyrdom of Saint Romulus is quoted verbatim, so to speak, from one of the bystanders in Jacopo Caraglio’s engraving of the Marriage of the Virgin after Parmigianino. No less deserving of comment, for all that it is bafflingly hard to explain, is the fact that the priestly donor figure who inhabits the bottom left-hand corner of Portelli’s altarpiece of the Annunciation from his home town of Loro Ciuffenna near Arezzo has been equipped – presumably at a later date – with a halo.

Annunciation of the Virgin (1555), Carlo Portelli. Loro Ciuffenna (Arezz), church of Santa Maria Assunta

Portelli emerges from his months in the sun as a talented artist understandably happy to learn from such Florentine near-contemporaries as Rosso Fiorentino, Pontormo, and Bronzino, but also to go his own way. His is an entirely distinctive and recognisable hand, and he is unarguably at his best as a painter of altarpieces. This may come as something of a surprise, since the received wisdom is that minor artists find it hard to rise to the challenge of grander projects, but Portelli copes wonderfully well with the demands both of the static Madonna and Saints type and of religious narrative. What is more, he is singularly unfazed when – as in both the Martyrdom of Saint Romulus and a representation of Heraclius Returning the Cross to Jerusalem – he is faced with all but unprecedented subject matter. And whisper it not – lest Borghini get wind of it – but the Accademia Immaculate Conception is surely his masterpiece.

‘Carlo Portelli: Pittore eccentrico fra Rosso Fiorentino e Vasari’ is at the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, until 30 April.

From the April issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.