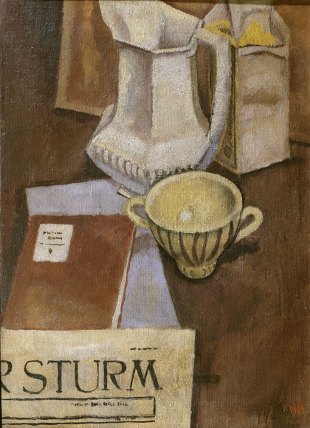

Nina Hamnett was ‘deadly serious about painting’, as she put it in Laughing Torso, a collection of her reminiscences published in 1932. A photograph of her as a young woman in her studio shows her standing with confidence, obscuring her easel, in wide-legged crêpe trousers and sandals, a cigarette in hand, her expression both earnest and ironic. At art school, under the tutelage of William Nicholson, she learned still life, placing objects – everyday, domestic things: an inkwell, an hydra jug, a two-handled cup, a small glass of white wine – not-quite squarely within the frame, the objects cropped at their edges. She disobeyed the conventions of the genre: no luminous porcelain, no flowers; the paintings do not glow. Her palette was London rooftops on a grey afternoon, solid browns and gloomy greens reflecting the material conditions of the paintings’ setting: a wooden tabletop in a rented room in Fitzrovia. In portraiture, she went beyond formality, finding ways to convey frankness, intimacy and humour. Sickert gave her advice on painting, which she ignored; she modelled, learning from her own form, but for the most part, she taught herself. ‘I painted a life-size portrait of myself in the looking-glass. The colour was very dull but it was well drawn.’

Der Sturm (1913), Nina Hamnett. Private collection. Photo: © Bridgeman Images

At Charleston, three decades of Hamnett’s work are on display in what is the artist’s first survey. The majority of the works date from the 1910s and ’20s, when Hamnett worked at Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops (though her style wasn’t naturally decorative; Bloomsbury was bread-and-butter work), shuttled on the boat-train between London and Paris, and kept company in bars and studios with Gaudier-Brzeska, Modigliani and Picasso. Laughing Torso recounts her adventures in Paris: masquerading as a boy in a cloth cap, dancing at cafes for three nights on the trot. She got by on Omega money, or from selling Modigliani drawings from a folder she hawked under her arm. She roved, and yet despite her proximity to artists and her immersion in the cultural exchange between cities, Hamnett’s work was entirely her own. Her paintings are sure of themselves, unwavering, concentrated with charisma.

Reclining Man (1918), Nina Hamnett. Private collection. Photo: courtesy Sotheby’s

Hamnett’s portraits are intimate or austere. She painted artists and friends – the French-Russian Cubist sculptor Ossip Zadkine, the Japanese dramatist Torahiko Khori (a jug of pink and yellow flowers behind his head) – and, in works on display from between 1918 and 1932, a series of queer young men. Full-lipped and pink-cheeked Anthony Butts (Cedric Morris painted his sister, Mary, less flatteringly); Rupert Doone, aloof, with almond eyes and a small pink mouth. In Reclining Man (c. 1918) the intimacy between artist and sitter is most apparent: the man is in shirt sleeves, cupping his head in one hand, cradling a glass of wine in the other. A fellow outsider in a makeshift, urban setting; it has all the directness, the empathetic curiosity, of a painting by Alice Neel.

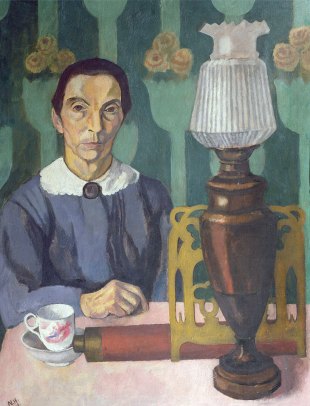

The Landlady (1918), Nina Hamnett. Private collection. Photo: © Bridgeman Images

Hamnett made sure she was always on the wrong side of propriety. She looked shrewdly at gentility. In the two portraits of her London landladies, she depicted a stand-off, a silent war. One woman, compact, with a helmet of nut-brown hair and a puritan collar on her dress, sits behind a barricade of objects; the other, in a fur mantle, beside a bowl of lustrous, touchable oranges. She has selected a single apple for her plate.

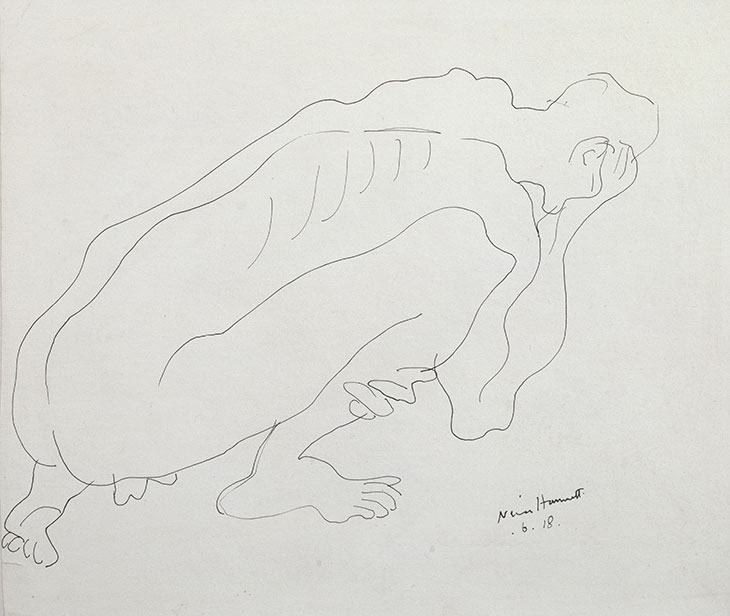

A final room at Charleston contains a selection of drawings. In Parisian cafes, Hamnett worked quickly and elegantly: a group decked out for a funeral, George Moore and Lord Alfred Douglas at the Café Royal. In London, she drew figures from the life. A crouching Roger Fry, head in hand, malnourished and yet revealing the tenderness of their relationship.

Study of Roger Fry (1918), Nina Hamnett. Private collection. Photo: © Bridgeman Images

Seriousness was not what Hamnett became known for. The energy she contained in her paintings spilled over into her glass. After the mid 1930s, when she mostly gave up painting in oils (although she continued to paint watercolours), she self-fashioned herself the ‘Queen of Bohemia’ and was to be found in Soho bars. Her wildness is tangible in her paintings, in the lips of her sitters, in colours used only once – dabbed on later? – and so distinct from the rest of the palette. Cherry-red for Ossip Zadkine, vivid peach for Rupert Doone. A dash of verve, of flesh and blood.

‘Nina Hamnett’ is at Charleston, East Sussex, until 30 August.