In 1942, when the contents of the National Gallery had been evacuated to a Welsh slate mine to protect them from bombing, a letter to The Times expressed a sense of deprivation with the collection inaccessible to the public, and a longing for the consolations of art. The writer claimed that, with the face of London ‘scarred’ and unlovely, ‘we need more than ever to see beautiful things’, and requested that individual paintings be brought back and exhibited. In response, the gallery began its still ongoing practice of nominating a ‘picture of the month’. The first to be returned from exile in the mines was Titian’s Noli Me Tangere (c. 1514): tens of thousands of people came to view it.

It is not hard to see why the painting would have appealed, and not just because retrieving it from a hole in the ground echoed its subject, of Jesus’s resurrection from the tomb. The composition is beautiful: the meeting between Jesus and Mary Magdalene, draped in sumptuous red, takes place before an Italian landscape in which a pastoral foreground recedes into a hazy blue and a sky lit up by the first inklings of dawn, brought delicately into the foreground by the touch of white on Jesus’s mattock. The moment is a turning point, in which grief is turned to wonder, and suffering recouped in joy: the first encounter with Jesus after the Resurrection, as told in the 20th chapter of the Gospel of John. Mary Magdalene, weeping at Jesus’s tomb, which she has discovered open and empty, encounters a man whom she takes for a gardener. She asks him if he knows where Jesus’s body is. In response, the gardener says only her name: ‘Mary’. She turns towards him, and realises he is the resurrected Jesus. It is a recognition scene: a narrative motif of comedy and romance, in which mistaken identity is resolved, a relationship believed interrupted by death renewed, and joy redeemed from disaster. In such scenes, as often in Shakespeare, there is a pervading sense of wonder at the happy unlikeliness of it all, which Titian renders in the slow dawning of the light over the verdant landscape, and Mary’s tentative hand and upturned wondering face. The reaching and inclining arrangement of the reunited Jesus and Mary is exquisitely touching.

Noli Me Tangere (c. 1514), Titian Photo: © National Gallery, London

Or rather: it isn’t touching. The telling of this moment in John contains awkwardnesses and lacunae of explanation that have always challenged interpreters. Why does Mary mistake Jesus, for whom she is ardently weeping, for a gardener? (Depictions must decide whether to show Jesus in workman’s clothes and with agricultural tools, suggesting a deliberate disguise and courting bathos; or insinuate that Mary doesn’t recognise the very person for whom she is looking, by showing him without them.) Most challenging, however, are Jesus’s words immediately after the moment of recognition: noli me tangere, or ‘touch me not’. It is difficult to hear the injunction as a friendly or a loving one, and John gives us no explicit guidance as to tone. Does Jesus speak with alarmed recoil? With gentle reproof? The words presuppose an instinctive reaching from Mary, just as Titian depicts her, and thus must come for her as an unaccountable rebuff, what Joe Moshenska, in a wonderful book on the Renaissance sense of touch, has called a ‘baffling brusqueness’. It is an abrupt suspension of their intimacy: in previous episodes, she had washed his feet with her tears and dried them with her hair, and anointed his head with precious oils. The pot that she usually carries contains a chrism, which recalls and anticipates such reverent touching. To be spurned is a hurt; it is an embarrassment. ‘Make the best of it,’ wrote the Jacobean preacher Lancelot Andrewes in his Easter sermon on the scene, delivered in 1621, ‘a repulse it is: but a cold salutation for an Easter-day morning.’

The challenge facing artists, then, is how to depict Mary’s longing for touch, and its repulse, kindly. How to signal love in an injunction not to touch, how to affirm bonds that cannot be ratified with a reach across the gap? It is a question of tact – a word itself derived from the Latin tangere, to touch – in depicting not touching; and a problem of how to dispose bodies in space. The French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy’s essay on the noli me tangere motif sees in Titian’s painting ‘a very singular combination of distancing and tenderness’. To be ‘distant’ is, etymologically, to be standing apart, or standing as two: and the art of noli me tangere is to render two figures in a distancing which is still social, still loving. Mary’s posture in many of the depictions renders her shock and her yearning: she leans towards Christ; seeks to lessen the distance between them; her hand attempts to meet his. Love, wrote the Catholic martyr St Robert Southwell in his Marie Magdalens Funeral Teares of 1591, ‘preferreth the least coniunction before any distant contentment’; but the preference is disappointed. The scene challenges us to conjure comfort and content in distance.

Noli Me Tangere (c. 1442), Fra Angelico. Museo di San Marco, Florence Photo: Azoor Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

Titian, as Nancy suggests, manages this beautifully. Christ gathers his garment out of Mary’s reach, but inclines his body and his gaze over her, withdrawing and protecting simultaneously. He softens the scene’s awkwardness by making of the two figures a dyad, a triangular compositional whole, which gathers up the internal dynamics of attention, yearning, separation, and care into a single arrangement. Fra Angelico’s fresco of c. 1442 in San Marco, Florence, likewise disposes the figures in triangular relation, but renders Christ’s loving distance in his ambivalent stance: though facing the viewer, his feet are reversed on the floral carpet, his right leg crossed over his left. His gently reproving hand and gaze turn to Mary tenderly, however. Philologists take the sting out of the imperative noli me tangere by pointing out that the Latin is a tendentious translation of something less stark in Greek. The koine phrase Μή μου ἅπτου, they claim, is better translated as ‘stop clinging to me’, or ‘don’t detain me’. Jesus tells Mary not to touch him ‘because he is not yet ascended to [his] Father’. Correggio’s rendering of c. 1525, now in the Prado, has Christ’s left arm dramatically pointing upwards to indicate the heaven from which he should not be held back, and on which Mary too should fix her attention, and on which she too should fix her attention. Fra Angelico’s crossed feet keep him more subtly on the point of departure, a way of salving separation, making the moment of reunion also a tender farewell.

Noli Me Tangere (c. 1525), Correggio. Museo del Prado

The tenderness is less obvious in the striking noli me tangere painted by Hans Holbein in 1526–28, now in the Royal Collection and hanging at Windsor Castle. When the diarist John Evelyn saw the painting in 1680, he declared that he ‘never saw so much reverence & kind of Heavenly astonishment, expressed in Picture’. The scene is certainly full of wonder and dramatic effects of light. But Holbein, rather than lessening the awkwardness of the encounter, has exacerbated it, pressing the comedy of recognition towards bathos. Glenn Most, in a book on doubting Thomas whose story appears in the same chapter of John, observes that Mary’s mistaking Jesus for ‘a silly Gardiner’, as Southwell puts it, ‘in another genre would be almost comical’. Holbein’s rendering brings that silliness to the fore. The turning and withdrawing of his Mary and Jesus are more obviously dynamic, reactively in motion, than in Titian or Fra Angelico. Mary, called by name, has just turned back, and, having recognised her beloved Lord, is reaching for him. Her movement is met with recoil, Christ stepping backwards while his raised hands and stern face ward off her urgency. There is, however, a kind of choreographic grace within the ungainliness, in the reciprocity of the placing of their feet, the distribution of weight in forward and backward momentum. The framing of the fleeing figures of Peter and John, who had gone to the tomb with Mary but left on not finding Jesus there, loads the gap between their bodies with narrative content. Holbein shapes the space of not touching as a live arena, full of energies of relation.

Noli Me Tangere (1526–28), Hans Holbein the Younger. Royal Collection Trust. Photo: © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

He also makes particularly vivid another of the significant dynamics of the scene. The tomb from which Mary has just turned is luminous, lit from within by a preternatural source, making dazzling the faces of the angels within. Nancy talks of ‘the radiant emptiness of the sepulchre’ – something manifestly true in Holbein, in which the almost electric brightness in that interior space contrasts with the natural dawn suffusing the sky from whiteness at the low horizon to the lit edges of cloud banishing the upper darkness. The contrast suggests two ways in which the story thinks of turning points: as the abrupt interruption of miracle, on the one hand, and the quotidian wonder of the return of the dawn, on the other. The same is true even when artists render the tomb as a zone of dark rather than light. In Fra Angelico, the tomb is a lozenge of uninflected black, the nullity of death from which Jesus has emerged, and the liturgical blankness salved by Easter. In Rembrandt’s painting of 1638, the tomb is a massive smudge of darkness, a hollow in the rock at the entrance to which the angels lounge, and towards which Mary’s attention was evidently directed before she was surprised by the supposed gardener. The tomb, in Rembrandt’s painting, is the focus of a gloom that absorbs the whole of the right-hand side; the dyad of Mary and Jesus is a fulcrum across which the painting switches from darkness into light.

Christ and St Mary Magdalene at the Tomb (1638), Rembrandt van Rijn. Royal Collection Trust. © her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Paintings of the episode often generate their composition and their energy from such patterns of opposition – light and darkness, sky and earth, standing and kneeling, reaching and withdrawing, body and spirit – which signal the pivotal instant of the recognition scene, and of the Resurrection, with its turn from tragedy into comedy. The binaries of contrast are even more intensely a matter of the work’s own execution in renditions of the scene in the cutting arts of woodcut and engraving, which work through the manipulation of monochrome effects, and practical questions of presence and absence. In the noli me tangere in Dürer’s Small Passion (c. 1510), Mary and Jesus are again the triangular focus of the composition. The sun, emerging over the horizon, forcefully irradiates the sky, a density of dark rays supplying both light and depth, making the whole background recede dramatically from the central figures. Patches of blank paper elsewhere – the landscape leading to the entrance to Jerusalem, the right-hand side of Jesus’s body, some foliage, the blade of his spade – concentrate the light. Like Rembrandt’s painting, Dürer’s engraving has a line of pivot along the spade, whose handle is dark but whose blade is bright. But like the unnatural radiance of Holbein’s tomb, the light on Jesus’s side, and especially on the spade, makes no sense in relation to the sun as a light source, the stuff of miracle rather than nature.

Dürer does not show the tomb explicitly, but it is present nonetheless not only in story, but also in his deployment of what Nancy called ‘radiant emptiness’, bright absence, itself the result of the excavatory work of woodcutting. In the context of noli me tangere, the technics of woodcut take on a theological pertinence. Sharp tools – knives, gouges, chisels – are used to excise wood, leaving the lines of the drawing standing clear in relief. Jesus’s spade, the signal, along with his wide-brimmed hat, of his disguise as a gardener, recalls the purpose of these tools, as well as his own recent entombment in the earth, and his Harrowing of Hell (though the tempting pun on ‘harrow’ as an agricultural tool is an accident of English etymology). Paradoxically, the wounds on Christ’s hands, black marks representing holes in his flesh and displayed to Mary as proof of identity, achieve their visibility by not being gouged. The patches of light, meanwhile, come in the woodcut from matter dug out: it is withdrawal which makes possible the radiance. Absence is in woodcuts the precondition of presence, just as Jesus’s removal from the space of the tomb, blank or bright, is the condition of his appearance in person. The question of contact and lack of it – the whole issue of noli me tangere – is key to the two stages of making woodcuts: the maker’s tools touch the woodblock not at the depicted lines but in the gaps between them, establishing salience through vacancy; in printing, however, it is the dark lines of the inked woodblock that make contact with the surface of the paper, framing the gaps of white that become the significant spaces of the image.

Christ Appearing to Mary Magdalene (c. 1510), Albrecht Dürer. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

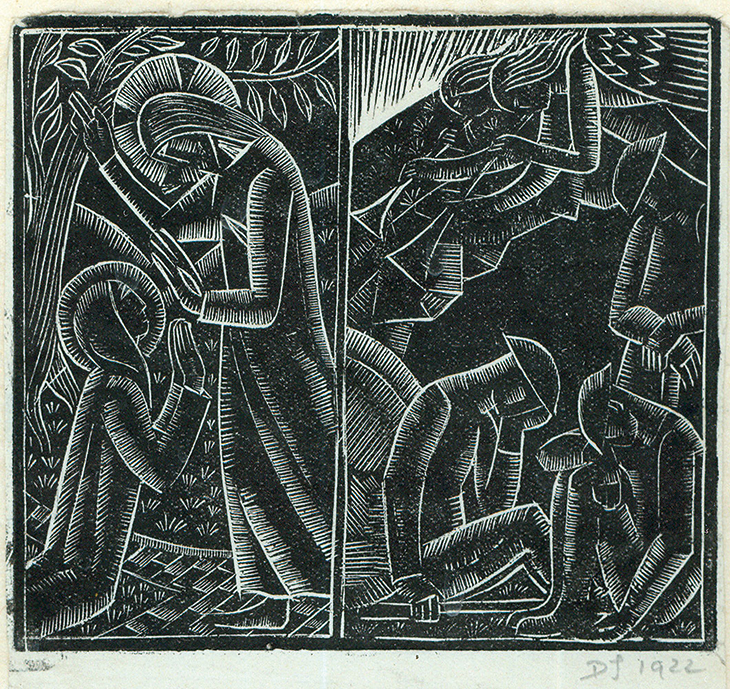

The same is true, though in reverse, in David Jones’s beautiful wood engraving Noli Me Tangere/Soldiers at the Tomb (1922). Here, a similar idea about the meaning of touch and the tomb is expressed by inverted means. In engraving, lines cut into the wood show white, giving a chalky radiance to Jones’s figures; blank space is, correspondingly, black. On the right-hand side of the picture, sleeping soldiers – at once the biblical Romans set before the tomb to guard it, and exhausted servicemen of the First World War – rest before the absolute black of the tomb space, from which, in their inattention, the stone has been rolled back. The tomb here is also a dugout, at once historicising the noli me tangere in Jones’s recent experience and making reference to the gouging and digging tools that are the common implements of the artist and of Christ as gardener, though here, paradoxically, rendered through the largest untouched section of the block. It makes literal and contradicts the latent pun in ‘engraving’ at the same time. The tomb’s dark is the only uninterrupted expanse of blankness in the image: everywhere else, ground is diversified with paving or grass, surface with contour, sky with rays. The angels’ trumpets direct us instead to the twofold figure of Mary and Jesus, the bright counter to the blankness of the tomb. Here, the avoidance of touch has moved directly into benediction, and Mary, rather than reaching for Jesus, raises her hands as if to receive a blessing, a willing acceptance of distance.

Noli Me Tangere/Soldiers at the Tomb (1922), David Jones. Photo: courtesy JHW Fine Art; © The Trustees of the David Jones Estate/Bridgeman Images

Nancy encourages us to think about the painter approaching the canvas with his brush as being engaged in at once touching and not touching the hands and bodies of his subjects. The painter is separated from them by the length of the handle of the implement, through which his or her own ‘touch’ is what gives the image its texture and qualities of colour. In Dürer and Jones, we see how intensely these technical questions inhabit the noli me tangere when rendered by the cutting arts, where the questions of whether and how a surface is touched, and the delicacy of not touching, are precisely the tact and skill of the artist.

The artist’s relation to the touching of art is different from ours. Even if we could visit these paintings now, we couldn’t touch them. The need to see beautiful things, expressed by the Times correspondent in 1942, involves at the same time a conscious adoption of the posture of reverent distance. There is a paradox here. On the one hand, our scrutiny and admiration of great works, and our desire to see originals, rest in part on their tangibility, their touchability, and their relation to the touch of the artist who made them. The cultural historian Constance Classen cites Bernard Berenson’s claim that an artist’s first purpose is to ‘rouse the tactile sense’, somehow creating ‘the illusion of being able to touch a figure’. Rembrandt’s contemporaries saw his thick impasto as an invitation to the touch – and he was himself known, on occasion, to paint with his fingers, rather than a brush. But that aroused desire is also forbidden: the paintings themselves, or at least the galleries that house them, issue a noli me tangere. The very thing which the object invites is also what it resists. The gallery context – alarm systems, wires, glass enclosures – acts as the equivalent of Jesus’s apotropaic gestures of distancing. In a response to Rembrandt’s depiction of the noli me tangere episode of 1638, the Dutch poet Jeremias de Decker claimed that looking at the painting led him to ask himself whether he had ever seen ‘doode verw soo na gebrogt aen’t leven’, ‘dead paint brought so near to life’. The artist’s invention and skill work on the dead matter of paint a kind of resurrection. Like Mary, marvelling at her risen master, the viewer of the noli me tangere is invited to recognise that resurrection, and marvel at it, while still resisting the urge to touch.

From the June 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.