From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In the autumn of 1606 the painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio arrived in Naples, hotfoot from Rome, fleeing a death sentence for murder. Protected by the Colonna family, he worked for eight months on important commissions for the Church before heading to Malta. Another violent incident forced him to leave Malta for Sicily, and then, in 1609, to seek refuge again in Naples, where he spent less than a year before heading to Rome to seek pardon; he died en route. Though his time in Naples was brief, Caravaggio’s impact on the city’s art was seismic. The most significant cultural and commercial centre in the Mediterranean, Naples had come under Spanish Habsburg rule in 1516. By 1600 it boasted a cosmopolitan population of 300,000, making it the second largest city in Europe, after Paris; by 1656 that had swelled to 450,000.

The Spanish viceroys – repressive rulers and punitive taxers – were enthusiastic patrons of art, as were the churches and religious orders, which vied to attract the best artists from all the kingdoms of Italy and beyond. Caravaggio’s dramatic expression, emphatic naturalism and intense chiaroscuro suited this febrile society, with its violent contrasts of wealth and poverty, splendour and misery, its riots, plagues, earthquakes and explosive volcano.

Giovanni Battista Caracciolo was the first to develop a distinctive Neapolitan Caravaggism, adopting from late 1606 a sombre palette and moulding his sculptural figures with vivid contrasts of darkness and light. Jusepe de Ribera, born in Spain in 1591, arrived in Naples in 1615 via Parma and Rome to become another key figure in the emergence of a Neapolitan school. Though he stayed in Naples for the rest of his life, his stark, tenebrous martyrdoms and half-length portraits of humble people won favour with the city’s Spanish elite and went on to influence the development of painting in Spain. Ribera and Caracciolo fought off competition from other major artists for commissions – including the Neapolitan Massimo Stanzione, the influential Annibale Carracci, his pupil Domenico Zampieri (Domenichino) and the more classically inclined Guido Reni, all three from Bologna.

Christ calling Saints Peter and Matthew (c. 1680–85), Luca Giordano. Courtesy Lullo Pampoulides (in the region of €500,000)

Strikingly different painters emerged from this melting pot: Salvator Rosa, Bernardo Cavallino, Mattia Preti and the anonymous Master of the Annunciation to the Shepherds. The devastating plague of 1656 killed many, including, we think, Cavallino, but a distinctive Neapolitan baroque style continued to evolve in the exuberant work of the prolific Luca Giordano and the later, more restrained frescoes and canvases of Francesco Solimena and his school.

Neglected for much of the 20th century, Neapolitan painting enjoyed ‘a resurgence of interest’, according to Alex Bell, chairman of Old Master Paintings, Sotheby’s, after a landmark exhibition at the Royal Academy in London in 1982. In 1983 the National Gallery bought Luca Giordano’s painting Perseus turning Phineas and his Followers to Stone (1660). Peter Moores bought Neapolitan paintings in the 1990s for his 18th-century mansion and public art gallery at Compton Verney, recognising they represented good value. Meanwhile, the market for the sumptuous still lifes of artists such as Luca Forte, Paolo Porpora, Giuseppe Recco and Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo was strong in Italy in the 1980s and ’90s. Today, Bell reports, interest remains high for ‘exceptional works in wonderful condition’ by artists such as Ribera, Giordano, Preti and Solimena. Institutions are making ambitious purchases. In January 2023, in the sale ‘Baroque: Masterpieces from the Fisch Davidson Collection’ at Sotheby’s New York, the National Gallery of London bought Cavallino’s fine Saint Bartholomew (c. 1640–45) for $3.9m, against an estimate $2.5m–$3.5m, while the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. bought Preti’s Man cutting a block of tobacco for $1.1m (est. $1m–$1.5m).

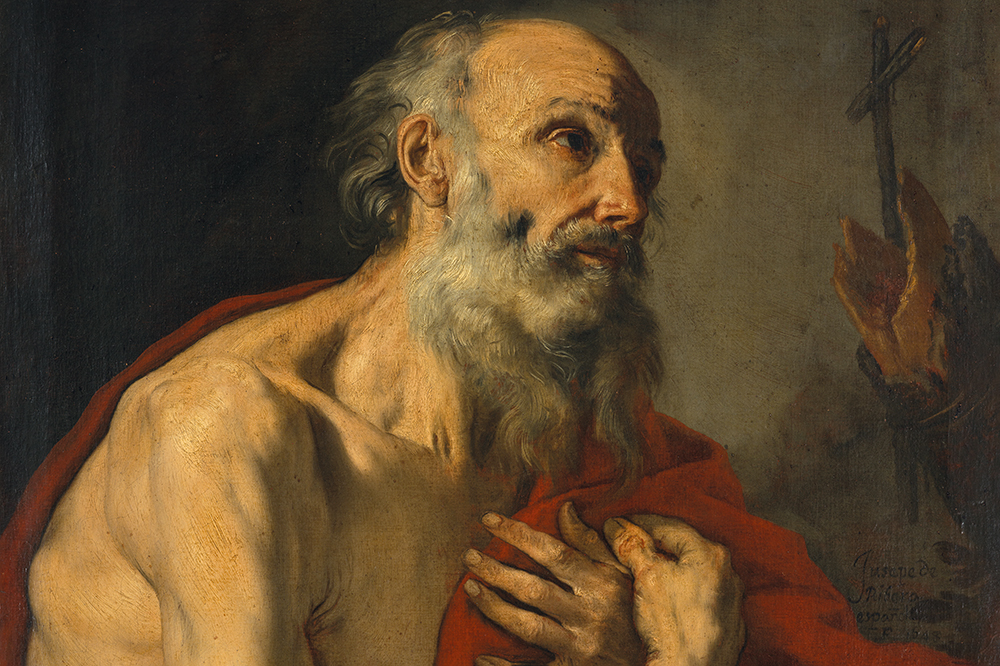

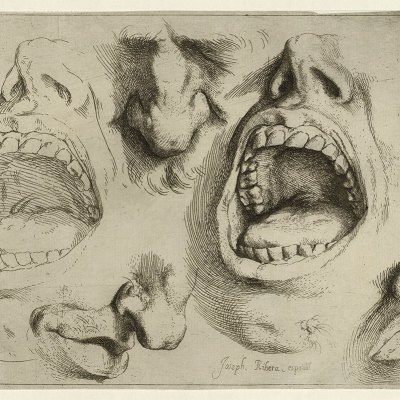

Eugene Pooley, a specialist in Old Master paintings at Christie’s London, confirms the strong institutional interest, adding that buyers are highly selective ‘about condition and provenance’. He cites the Saint Jerome by Ribera, dated 1648, which fetched €2m, against an estimate of €500,000–€800,000, at Christie’s Paris in June 2023: ‘This was in lovely condition, signed and dated.’ Ribera’s current high status has been reinforced by shows such as ‘Ribera: Art of Violence’ at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2018, the first devoted to the artist in the UK. ‘When we get a great Ribera there is always great interest. If the quality is there, there is no inhibition about difficult subject matter.’ A catalogue raisonné of 2018 has helped the market for Solimena by sifting signature work from the vast studio output.

The New York-based Old Master dealer Robert Simon confirms Ribera’s current appeal: ‘Ribera is both among the most desirable and obtainable, if one were to include the paintings of his active workshop.’ He points to A Girl with a Tambourine (1637) which sold at Sotheby’s London in July 2019 for £5.7m (est. £5m–£7m). Simon’s recent exhibition ‘Luca Giordano in New York’ was a first solo show for the artist in the city. He says, ‘I don’t think the market has changed all that much. There are passionate collectors in the field and there are newcomers to it, but against that, there is a general narrowing of interest in Old Masters generally.’

Saint Jerome (1648), Jusepe de Ribera. Courtesy Christie’s, €2m

In the United States, interest is boosted by a large Neapolitan diaspora: ‘I have at least two serious collectors who trace their ancestry back to Naples and who focus on Neapolitan paintings.’ Simon also confirms institutional interest: ‘The Dallas Museum of Art and the Minneapolis Institute of Art have made important Luca Giordano acquisitions in recent years. We sold a highly important Mattia Preti to the Saint Louis Art Museum in 2017.’ The appeal of Neapolitan baroque paintings lies, he thinks, in their often dark tonality and subject matter, reflecting Caravaggio’s influence. ‘Figures dramatically emerge from darkness and shadow, and the pictorial themes are powerful, passionate, and visceral. That attracts many (but repels others!).’ Among many pictures, he has available a recently rediscovered Giordano, A Guardian Angel Leading a Child ($375,000).

Andreas Pampoulides of the London dealership Lullo Pampoulides notes the rise in interest in women baroque painters, including Artemisia Gentileschi, who moved to Naples in 1630 and remained there until her death in the mid 1650s: her fame and value have ‘skyrocketed’ in the last decade. In 2017, the gallery rediscovered an early work by the Neapolitan artist Andrea Vaccaro, which sold to the Finnish National Gallery in Helsinki. At the Florence International Antiques Fair (BIAF) in September it will show an important work by Giordano: ‘Giordano’s value on the market can vary massively, from under £100,000 to well above £1,000,000, depending on quality, subject, period, condition and provenance. A Giordano or a Preti from the 1650s is normally worth more than much later ones.’

But Fabio Obertelli, curator at Giorgio Baratti Antiquario in Milan, detects a new interest in Giordano’s Florentine period in the 1680s, perhaps inspired by ‘Luca Giordano: Maestro barocco a Firenze’ at the Palazzo Medici Riccardi in 2023. He has, however, noted a long-term decline in interest in Neapolitan still lifes; instead, collectors seek out ‘the various versions of Mary Magdalene or Lucretia done by Andrea Vaccaro, Ribera’s old and wrinkled-skinned saints, or Luca Giordano’s fantastic and complex mythological compositions’. The gallery holds a wide range of stock, from monumental works by Ribera to ‘a stunning Maddalena by Andrea Vaccaro’. Among a selection it will take to BIAF, the gallery will show a couple of oil on glass paintings by Giordano. The London gallery Cesare Lampronti will show a powerful painting of Salomé by Caracciolo at the fair. Gallery manager Anna Chiara Giusa reports they still have enthusiastic collectors of Neapolitan baroque still lifes, but when it comes to figurative painters, the message is simple: ‘Clients are looking for a masterpiece.’

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.