From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

On 19 February 1946, a glittering audience arrived at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. They were unfashionably early – public transport had not yet returned to its pre-war levels – and their fine clothes smelled strongly of mothballs. Nevertheless, they were distinguished. An auditorium that had spent the war as a Mecca dance hall now hosted several members of the royal family, as well as Clement Attlee and Ernest Bevin, prime minister and foreign secretary in the new Labour government. At 7pm, in the orchestra pit, Constant Lambert began conducting the frenetic fanfare of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s overture, and moments later the curtain rose on the Sadler’s Wells Ballet Company performing Marius Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty, adapted from Charles Perrault’s story of a princess cursed to sleep for 100 years. Bursting on to the stage in a two-toned pink tutu with silver swags and gauzy sleeves (her entrance tantalisingly delayed until after the first interval) was the 27-year-old Margot Fonteyn, the embodiment of the teenage Princess Aurora, the sleeping beauty herself.

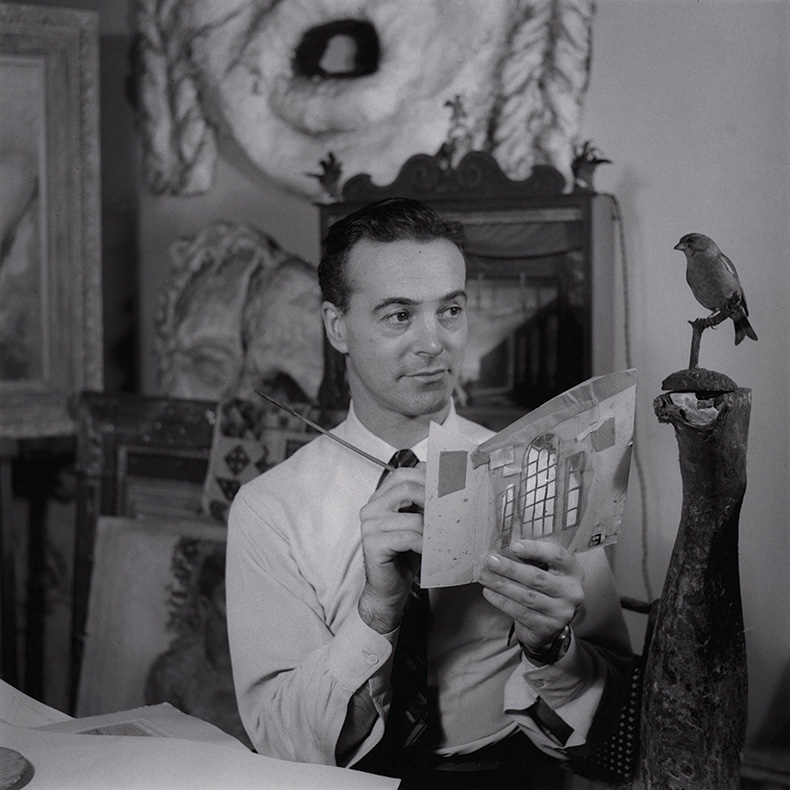

Oliver Messel (1904–78), photographed in his studio in 1945 by Francis Goodman (1913–89). National Portrait Gallery, London. Photo: © Estate of Francis Goodman

Fonteyn’s pink costume and the fantastical painted palace in which she danced were the work of Oliver Messel, one of Britain’s leading theatre designers. He had first attracted popular attention in 1932, with the set and costumes for Helen!, an adaptation directed by Max Reinhardt of Offenbach’s comic operetta La belle Hélène, based on the story of Helen of Troy. The production’s sensational white-on-white bedroom scene, with sculpted swans and cascading drapery, was at the vanguard of a new trend in interior design. By the time he received the commission for The Sleeping Beauty, Messel was known for combining ornate grandeur with strategic reinterpretation, and occasional pastiche, of 17th- and 18th-century art and architecture, usually based on extensive research. All of this is present in The Sleeping Beauty. In the decades that followed, the production was restaged nearly 1,150 times, including for the Sadler’s Wells Company’s triumphant 1949 American tour, which established Fonteyn as a global star. Periodically updated, it remains a key part of the repertory of what is now the Royal Ballet (the charter was awarded in 1956), and is perhaps Messel’s most enduring creation.

Messel’s rich historical sense was a product of a youth infused by art. He grew up between London and the family summer house at Nymans, West Sussex, where his parents, Leonard and Maud (daughter of the Punch cartoonist Linley Sambourne) had created a German Gothic vision around (and over) the Arts and Crafts house and garden designed by his paternal grandfather. The Messels surrounded themselves and their three children with antique furniture, Chinese and European porcelain, textiles and 18th-century prints. Rather than attending university, Oliver completed his education at the Slade, studying under Henry Tonks. However, a set of his papier-mâché masks, exhibited at the Claridge Galleries in 1924, caught the attention of both the theatre producer Charles B. Cochran and Serge Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes. Messel went on to create the masks for Diaghilev’s Zéphire et Flore, a short-lived mythological ballet by Léonide Massine, with costumes by Georges Braque, which premiered in Monte Carlo the following year. Though he was pulled inexorably and successfully into designing for the stage, his extensive career also included textiles, interior and architectural design, and a period working in film. In 1936 he created a Renaissance Verona on the MGM backlot, drawing on paintings by Piero della Francesca, Giovanni Bellini and Leonardo da Vinci for George Cukor’s Romeo and Juliet.

Margot Fonteyn (as Princess Aurora; centre) in Act I of The Sleeping Beauty at the Royal Opera House, London, in 1946. Photo: photo: © Frank Sharman/Royal Opera House/ArenaPAL; www.arenapal.com

The four sets and 200 or so costumes Messel created for The Sleeping Beauty allude primarily to the France of Louis XIV, with sprinklings of earlier Spanish and Venetian paintings and prints: Margot Fonteyn’s distinctively sleeved pink tutu loosely reinterprets Velázquez’s 1660 portrait of her namesake, the Spanish Infanta Margerita. The story of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ necessitates the passage of a century between the two halves of the tale, and while Messel’s sets for the Prologue and Act I borrow mainly from the 17th century – Carabosse’s chariot is derived from Jacques Callot’s series of etchings Le Combat à la barrière (1627) – Act II features peasants in China-blue dresses and pink bows, Sèvres porcelain brought to life. However, Messel was none too fastidious in this department, favouring a general historical mood rather than a precise representation of chronology. Puss-in-Boots dances in Act III in a blue coat and tasselled orange trousers with lace frothing at his collar and cuffs, a far cry from the sleek tailoring of Aurora’s Prince Florimund and his 18th-century court.

Margaret Dale (as the White Cat) and Stanley Holden (as Puss-in-Boots) in Act III of The Sleeping Beauty at the Royal Opera House, London, in 1946. Photo: © Frank Sharman/Royal Opera House/ArenaPAL; www.arenapal.com

The sets for the Prologue, Act I and Act II represented Aurora’s palace, with striped columns and huge arches softened by a billowing curtain framing a verdant landscape. All the architectural designs placed the building at an angle from the stage, a favourite trick of the Bibiena family, baroque scenographers whose innovative use of two-point perspective gave their looming interiors the appearance of extending far beyond the world of the stage. However, the dreamy arches and feathery trees Messel created for the Prologue have a direct source in Jean-Antoine Watteau’s Les Plaisirs du bal (c. 1715–17), a key painting in the rococo style. Watteau shows elegant merrymakers, dressed in a hodgepodge of theatrical costumes and contemporary aristocratic fashions, enjoying dance, music and convivial conversation before a sparkling fountain. The setting, also characterised by striped colonnades, has its own Bibiena-style double perspective, but as the image recedes, the brushstrokes and the quality of the paint become gestural and indistinct, making it unclear where the figures end and the trees begin. Messel’s fairytale landscape is similarly vague, softened with brushstrokes and draperies that recall his early training as a painter. The art dealer Edmé-François Gersaint, who put up Watteau during the final months of his short life, recalled with disapproval how his friend used to slather oil all over his brushes in order to spread the colour more quickly. Technical analysis confirms that Watteau built up his pictures up with layers and layers of virtually translucent glaze. The result is that, as John Constable observed, Les Plaisirs du bal looks as though it could have been ‘painted in honey; so mellow, so tender, so soft’. Messel had his own translucent tricks. He built The Sleeping Beauty up through innovative combinations of stage flats and gauzes. ‘You had a real staircase coming down, and then it turned a corner and it was just painted’, recalled the dancer Anya Linden, then a student at Sadler’s Wells: ‘Everything was flat, flat, flat.’

The Prologue of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet production of Marius Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty, designed by Oliver Messel and performed at the Royal Opera House, London, in February 1946. Photo: © Frank Sharman/Royal Opera House/ArenaPAL; www.arenapal.com

These illusions also served a practical purpose. Though Aurora’s awakening mirrored Britain’s emergence from the privations of wartime, rationing was still in place, making it virtually impossible to find silks and satins, artificial flowers, or good-quality paint and canvas. Messel was habitually uninterested in budgets, and his designs for The Sleeping Beauty – many now in the Victoria & Albert Museum – are characteristically light on practical detail. Aurora’s tutu for the ‘vision scene’ is represented by a series of white blobs of paint beneath a bodice that is

elaborately decorated but offers no clues about how it might be created. However, the vagueness of the designs belies the meticulousness of their maker: Messel made many of the props and costumes himself (though Fonteyn’s ever-present mother was also recruited to search for ‘brocades, feathers, braids, gimps and all kinds of unrationed bits and pieces’). Partly from invention and partly from the necessities imposed by the wartime conditions in which he had made his career, Messel was devoted to unorthodox materials such as rubber, Sellotape, cleaning clothes, pipe cleaners and sweet wrappers, conjuring many of his most fantastical creations out of almost nothing.

Costume design for King Florestan XXIV in Marius Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty (1945), Oliver Messel

The resulting spectacle fulfilled a dream long nursed by the company’s director, the indomitable Irish-born Ninette de Valois, who frequently boasted of having spent her formative years performing ‘the Dying Swan on the end of every pier in England’. After a stint in the Ballets Russes (where she and Messel first met), she had returned to England in 1924 determined to establish a native ballet school and company for Britain. A shrewd manager, she applied many of Diaghilev’s lessons, while reacting against the vaguely vagabond, provisional aura that hung about his company. With the support of the similarly indomitable Lilian Baylis, she was determined to make the Sadler’s Wells Company a national institution, a democratic British equivalent of the ballet of Imperial Russia.

However, just as Diaghilev had conceived and advertised Parade, Massine’s collaboration with Picasso, Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie, as ‘the world’s first Cubist ballet’, De Valois aspired to fuse ballet with contemporary visual art. She and her colleagues frequently sought inspiration in literature, trying to bring intellectual heft to an art-form which many early 20th-century British audiences still associated with music hall. In 1935, De Valois’s The Rake’s Progress was danced against sets inspired by William Hogarth but designed by Rex Whistler. During the Second World War, Graham Sutherland created the sets for Frederick Ashton’s Expressionistic The Wanderer, based on Schubert’s Winterreise. After Ashton was called up, choreographic carte blanche was given to the principal dancer (and sometime actor) Robert Helpmann, who created both a 20-minute Hamlet, with moody 15th-century-style designs by the painter Leslie Hurry, and Comus, based on a masque by John Milton. Oliver Messel was then working as a camouflage officer in the Royal Engineers, where his friend and colleague, the painter Julian Trevelyan, described him disguising pillboxes and vehicles as ‘caravans, haystacks, ruins and wayside cafés’. However, he knew Helpmann, having previously dressed him as Oberon (opposite Vivien Leigh’s Titania) in Tyrone Guthrie’s 1937 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. For Comus, which also featured Fonteyn, Messel created a 17th-century-inspired architectural folly with an expansive, ethereal landscape, complemented by Van Dyck-inspired costumes and headdresses, with no tutu in sight.

Set design for the cut cloth in Act I of The Sleeping Beauty (c. 1946), Oliver Messel. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Despite her willingness to embrace the contemporary, De Valois had a notable fixation on Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty, which she regarded as the peak of the classical style established in 19th-century Russia, and therefore the foundation on which she wished to build. Messel was perfectly attuned to her vision. In choosing to reference the world of Louis XIV, he was responding shrewdly to the ballet’s history. ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ is not an intrinsically 17th-century story. Charles Perrault, formerly a courtier at Versailles, had collected the original tale along with a group of other oral stories from a focus group of mostly illiterate working women and repackaged it for elite audiences in his Tales of Mother Goose (1697). However, in his lavishly illustrated edition of Perrault’s Tales, published in 1862, Gustave Doré gave the story a generic medieval setting; Edward Burne-Jones did the same in his Briar Rose series of panels at Buscot Park (1885–90), which shows the sleeping princess awaiting her prince among catatonic courtiers. A decade after Messel’s production, Walt Disney’s animated Sleeping Beauty (1959), which used Tchaikovsky’s score, took elements from the French rococo, but referred more directly to medieval illuminated manuscripts.

However, Petipa’s ballet, which received its premiere the same year Burne-Jones’s Briar Rose appeared at Agnew’s Gallery, was ideologically inseparable from the French 17th and 18th centuries. It was commissioned by the Francophile Ivan Vsevolozhsky, director of the Imperial Theatres, in the hope of establishing a modern Russian equivalent to the court ballets of 17th-century Versailles – productions such as the Ballet royal de la nuit (1653), per- formed before Louis XIV’s long-suffering courtiers from 6pm until a dawn finale that featured the 14-year-old monarch in his first appearance as the ‘Sun King’. Their star already on the decline, the late 19th-century Russian aristocracy regarded 17th-century France as a high point of enlightenment and autocratic rule, and Veselovsky and Petipa made strategic additions to Perrault’s tale to emphasise his monarchical allegiances. The ballet unfolds over a series of formal court occasions, and Aurora’s dynasty is at least as long-lived as the Bourbons, King Florestan being identified as the 24th of his name. Petipa’s choreography features baroque-inspired diagonal movement, spectacular group patterns and steely pointe-work, encapsulated in the fearsome balances of Aurora’s Act I ‘Rose Adagio’ (later to become a set piece for Fonteyn). The Mariinsky premiere was performed against heavily marbled Versailles-inspired backdrops, with illusory set pieces including a moving ‘panorama’. The carefully conceived combination of story, music, choreography and set consciously evoked the grand tradition of the earliest European court ballets, which frequently included sophisticated stage machinery and moving floats.

In 1921, Diaghilev was cash-strapped and searching for an easy commercial hit. He decided to restage Petipa’s ballet, for the first time before a Western audience, in the significantly less magnificent setting of the Alhambra Theatre in London. This production was designed by the Russian-Jewish designer Léon Bakst, who created a confection of Louis XIV and Louis XV styles, complete with ostrich feathers, ruffled pannier skirts, elaborate 18th-century wigs and implausibly heeled shoes. While referring to Enlightenment France, the set also included nostalgic echoes of the 19th-century splendour of autocratic Russia. Aurora’s bed was surmounted by an imperial eagle, whose threatening demeanour and imposing size seemed hardly conducive to 100 years of gentle repose, and one of the staircases was a direct copy of the steps in the Winter Palace. Bakst’s colours were rich, saturated and boldly contrasting, an aesthetic derived from the so-called ‘Oriental’ ballets he had designed for Diaghilev – The Firebird, Les Orientales and Schéhérazade (all 1910). De Valois (who danced in it) blamed the ultimate failure of Diaghilev’s Sleeping Princess partly on Bakst’s designs, which were notoriously difficult to dance in and generally recognised as the product of a bygone age. ‘The new ballet, which out-splendours splendour is more grand than vulgarly cheerful,’ wrote the Daily Mail. It conjured up ‘all the pomp of dead and done-with kings and emperors – Bourbons and Romanoffs’. In reaction, when she first staged Sleeping Beauty at Sadler’s Wells in 1938, De Valois went too far in the opposite direction. The muted sets and austere costumes she commissioned from the painter Nadia Benois reduced Fonteyn to tears.

Louis XIV in the guise of Apollo, 1654 (?), Henri Gissey. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© HM King Charles III 2023 (c. 1621–73). Royal Collection Trust Royal Collection Trust

Despite the ballet’s status as a war horse of tsarist Russia, Messel’s interpretation of The Sleeping Beauty was carefully positioned in France, the home of Perrault. His costume design for King Florestan XXIV imagines the fictional monarch resplendent in gold breeches, ostrich feathers and ermine, recalling Henri Gissey’s drawing of the ostrich-plumed Louis XIV in costume for the Ballet royale de la nuit. At the same time, while the sets of Petipa and Bakst had been imposing representations of dynastic and monarchical power, Messel’s was a light and airy fantasy, its architecture insubstantial and dominated by the natural world. As such, though it refers to the France of Watteau, the production also partakes of the landscape and watercolour tradition developed in 18th-century Britain by Richard Wilson and Thomas Gainsborough – and perfected by Constable, who spent so long in front of Les Plaisirs du bal. When Britain’s most famous home-grown ballerina ran on to the completed set in her rosy costume, The Sleeping Beauty was established not simply as a recreation of a canonical 19th-century ballet, but as a statement of British post-war identity, with a lineage that was not aristocratic, but artistic.

From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.