For many of the 58,262 people who attended Tottenham Hotspur’s opening Premier League fixture of the season against Manchester City, Son Heung-ming’s winning goal may have been the artistic highlight.

But a proportion of those who visited the club shop at the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium that afternoon hopefully discovered a rather different conception of footballing art, in the form of ‘Balls’, an exhibition at OOF Gallery (until 21 November). Established by the art critic Eddy Frankel and gallerists Justin and Jennie Hammond, the gallery is in Warmington House, an attractive Grade II-listed Georgian building that is accessed through the shop – official title, ‘The Spurs Experience’ – and owned by the football club.

‘Balls’ is, well, an exhibition of two halves: pieces by the Young British Artists of 25 years ago jostle for attention with contemporary work by young British artists, while a smattering of international stardust allows the visitor to think about what football means across the world – and how far it can claim to be a universal game.

World Cup Again (2002), Sarah Lucas, installation view, ‘Balls’, OOF Gallery, London, 2021. Private collection. Photo: Tom Carter; © OOF Gallery

The YBA pieces – Sarah Lucas, Marcus Harvey, Abigail Lane and Gavin Turk all have works exhibited – may be interesting in themselves. But they are also intriguing because the careers of those artists and the history of modern football overlap in so many ways. Charles Saatchi’s ‘Young British Artists I’ exhibition launched in March 1992, a few months before the inaugural Premier League season kicked off. Both quickly transformed what were perhaps moribund scenes into exciting (and moneyed) cultural touchstones for a wider population than had previously been interested. Art and football became outward looking, commercial, cosmopolitan and, eventually, ubiquitous. As football, art and the wider culture became more interrelated – Damien Hirst wrote an unofficial World Cup song – perhaps it was inevitable that these artists would end up being exhibited in a £1 billion stadium development.

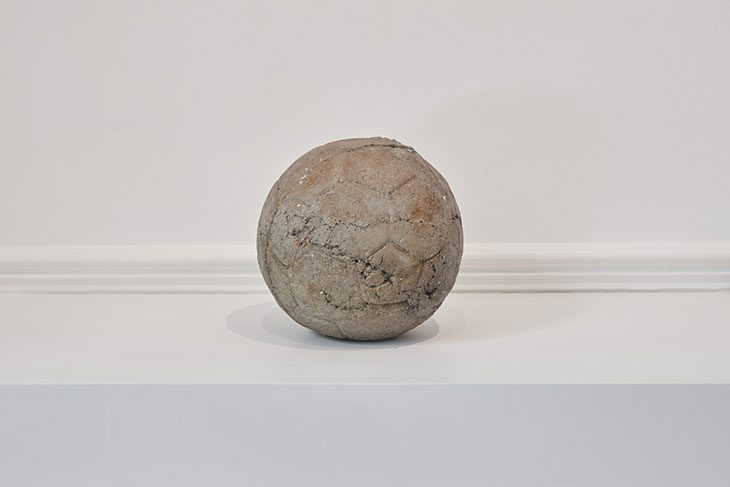

Their works here are terrific. Sarah Lucas’s World Cup Again (2002) is a heavy-looking (and actually heavy, presumably) concrete football, redolent of breeze blocks but also, somehow, of age, its worn hexagons and cracks suggestive of the historical and cultural weight that footballs and football carry. Similarly, with Victoria (2008), Marcus Harvey considers whether football is capable of standing for all the things we might ask it to. This scaled-up bronze cast of a deflating Victorian leather football, stitching gaping obscenely open, speaks of degraded symbols – of leisure, of nationhood, of empire – and an England clinging on to its past as the future overtakes it. It’s also physically arresting, inviting and cushion-like to the eye and, of course, hard and cold to the touch.

Victoria (2008), Marcus Harvey, installation view, ‘Balls’, OOF Gallery, London, 2021. Private collection. Photo: Tom Carter; © OOF Gallery

What does football stand for? It’s a question many of the artists here ask. The answers are not always comfortable.

The young British artist Jazz Grant’s powerful collage Canary in a Coal Mine (2021) consists of a leather football taken apart and stitched back together flat, like an illustration of a molecule. It’s covered with images of (mostly) male, white football fans, union flags and hooligans from the 1970s and ’80s, cut out and overlaid with silhouettes for missing faces. Grant has created something that feels (and almost smells) strongly of the past, and the violence not just of that era on the terraces, but of the society that gave rise to it – the exclusions of both society and football, the racism, the sexism. The implication is that things haven’t changed as much as we might think or want.

The maleness of football is a recurring theme in the exhibition. Nicola Costantino’s Male Nipples Soccer Ball, Chocolate and Peach (2000) is an amusing critique of machismo, the light hexagons on a football each featuring a ridiculous silicon male nipple. On a similar theme, but more outrageous, is the installation of Rosie Gibbens’ Team Building Exercise and Pre-Match Ritual (2021). Inspired by a tour of the Spurs’ changing room, it features garish prayer kneelers with football boot brand names across them, supplicant to a kind of female form that has teats poking out of footballs as if inviting the players to suckle. It’s funny, and gives a new meaning to the notion of ‘pampered footballers’.

Pre-Match Ritual and Team Building Exercise (both 2021), Rosie Gibbens, installation view, ‘Balls’, OOF Gallery, London, 2021. Photo: Tom Carter; © OOF Gallery

Sometimes, of course, the joke needs to be made explicit. J.J. Guest’s Balls (2021) consists of two globes made of bone china and hung in a net sack, testicular and wry. Dario Escobar’s Obverse and Reverse XXXI (2017) also comprises hanging balls in sacks, though these are more like air sacs, stripped and internal, than dangling gonads. It’s beautiful and calming.

On match days, Spurs expect as many as 20,000 people to visit ‘The Spurs Experience’. If even a small fraction of that number find their way into ‘Balls’, OOF Gallery will more than justify its existence. Spurs are unbeaten so far this season, and for that this smart, direct and winning exhibition is the perfect match.

‘Balls’ is at OOF Gallery, London, until 21 November.