From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Everyone said we were mad,’ a serene Francesca Valsecchi admits with a smile as she recalls the decision she and her husband Massimo took in 2015, when they moved from an apartment in Cadogan Square in London to the colossal Palazzo Butera in Palermo. Neither had Sicilian roots. The baroque palace, which rises as a great bulwark between the sea and the old Arab quarter of the city, boasts an irresistible terrace, which stretches along the old city wall for more than 100 lushly planted metres overlooking the Gulf of Palermo. Its principal allure, however, was the potential of its cavernous interiors as a museum, study centre and home. For the Valsecchis, art and ideas have always gone hand in hand.

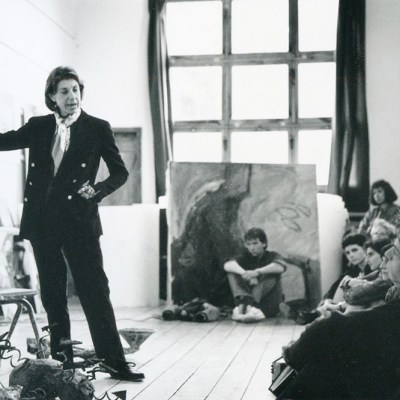

In a sense, the Palazzo Butera represents the realisation of a project some two decades in gestation. Back in 2002, while teaching a course at the University of Milan, Massimo Valsecchi saw the potential of the university’s repositories of books and archival material and began staging exhibitions presenting these multidisciplinary holdings alongside contemporary art. His aim was to encourage people to look in different ways, and to stimulate ideas by recognising the relationships between innovation in the arts and sciences, the present and the past. A scheme to expand the project into a permanent museum that would make imaginative use of the Valsecchis’ own collection ultimately collapsed through lack of funding. It was only a question of time before they took the project forward in another Italian city, and the couple were beguiled by the ‘forgotten’ historic Sicilian capital – unspoilt, hospitable and multicultural.

To the left in the Green Room are Pier Leone Ghezzi’s Musicians (c. 1715) and Self-Portrait (1695) by Giuseppe Maria Crespi. To the right is a cabinet by Charles Robert Ashbee (c. 1900) and Gilbert & George’s Piss (1977). Photo: Sandro Scalia

The Valsecchis’ singular and virtually unknown assemblage of fine and applied arts was unveiled by this very magazine (in the June 2016 issue of Apollo) – before its highlights were despatched on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The restoration of the Palazzo Butera complete, and those works of art now united for the first time with contemporary art in the collection long held in store, this author’s visit was overdue.

The subtlety and the glory of the Palazzo Butera project only gradually reveal themselves. A first hint of what to expect comes with the bold, jet-cut geometries of the oxidised iron gates commissioned for the entrance, the sleek ticket hall lined with conceptual art and the adjoining museum bookshop in the former palace archive, where unrecoverable documents found in the cavities between the walls are left visible – bound and stacked behind glass like an installation in a vitrine. In this most painstaking and sensitive of restorations, masterminded by Milanese architect Giovanni Cappelletti, the revelation of the long-hidden secrets of this much-remodelled historic palace is arguably the greatest attraction of all.

For the Gothic Room, the most dramatic of the commissioned interventions of Anne and Patrick Poirier, the artists designed a carpet and coloured mirrors with inscriptions in Latin and ancient Greek, alluding to Palermo’s richly layered multicultural history. Photo: Sandro Scalia

It is something of a miracle that the museum came into being at all – the island is littered with unfinished projects. The Valsecchis had bought the palace from no fewer than 27 princely heirs of Butera, who had been trying to sell it for 40 years. It was, inevitably, in far worse condition than they originally thought. A further complicating factor was that various heritage and planning authorities held sway over different aspects of the project. Such was the political will for the regeneration of the city, however, that its celebrated mayor Leoluca Orlando was able to bring their representatives around the table. Moreover, first-class traditional craftsmanship is still to be found in Palermo. ‘People understood they were not doing something for us but for themselves,’ explains Massimo. ‘They were proud to be part of the regeneration of a palace that had been here for 400 years and would be open to all.’

Extensive building work did, however, bring fortuitous discoveries. The least expected was the roots of the ancient jacaranda tree in the courtyard which, in its quest for water, had mined through a metre of stone and found irrigation channels built to bring rainwater from the roof to a long-forgotten underground cistern. Massimo was so struck by this demonstration of natural intelligence that he had the roots’ various channels lined with repurposed maiolica tiles rendered visible through a glass floor.

The former boiler room of the palace with the exposed underwater drain occupied by the root of an old jacaranda tree. On the left is a work from the Poiriers’ Theogonie series (1988). Photo: Michele Nastasi

Frescoes and wall paintings were also found under false ceilings and partitions, and the quality of all those remaining revealed through cleaning. Even so, 16 new ceilings were required. Given that planning regulations required them not to touch the walls of the state rooms, Cappelletti designed ingeniously curved suspended ceilings, which were painted by the English sculptor David Tremlett. Along with the artists Anne and Patrick Poirer, Tremlett worked in close partnership with the Valsecchis – the latest chapter in a series of collaborations that began when the Valsecchis opened an experimental art space in Milan in the 1970s. Indeed, many of the collection’s highlights are works commissioned but fortunately unsold from those years – by the likes of Tom Phillips, Gilbert & George and Andy Warhol.

Perhaps the most remarkable of the first-floor state rooms used by the Valsecchis (open twice a week on a guided tour) is the ‘Byzantine’ Gothic Room, where the commissioned Poirier rug and coloured glass panels offer a contemporary interpretation of Sicily’s Norman and Arab history. The revelation in terms of the transported collection, however, is how their British 19th-century Arts and Crafts furniture – not least among them the ‘Flax and Wool’ Gothic Revival cabinet by William Burges – holds its own in these grand spaces alongside the Italian Old Master paintings. It is almost as if these works have expanded to a world stage. More innovative fine and applied arts in all media are displayed in the 20 galleries of the second floor.

The Pink Room combines British Arts and Crafts furniture alongside Italian Old Master paintings. Flanking the door are the ‘Flax and Wool’ cabinet designed by William Burges in 1858 and Annibale Carracci’s Allegory with a Buffoon (1585). Photo: Sandro Scalia

It would take more than a single extended visit to unravel the complex web of connections linking the myriad works of art brought together for what Massimo describes as his ‘crazy Enlightenment project’. This label-less museum invites the viewer to make their own associations, or simply enjoy what they see. Massimo views the current display as a starting point, just as the palace’s conference rooms and scholar accommodation – already host to scholars from Oxford University and courses run by University of Rome, La Sapienza – are open to developing further partnerships with overseas and regional cultural institutions. Through the Fondazione Butera, established by Francesca’s daughter Silvia Le Marchant and her husband Piers, the Palazzo Butera is poised to fulfil its role as a 21st-century incubator of ideas.

From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.