Introducing Rakewell, Apollo’s wandering eye on the art world. Look out for regular posts taking a rakish perspective on art and museum stories.

Keats wrote more than one sonnet about an encounter with ancient Greece. ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’, for instance, is one of the most stirring recreations of intellectual excitement there is. ‘On Seeing the Elgin Marbles’, however, is an altogether more depressing affair. Looking at the sculptures – which had been on display in London since 1807 – makes the poet feel that ‘each imagined pinnacle and steep / Of godlike hardship tells me I must die / Like a sick eagle looking at the sky’. (Quite unlike the Chapman’s Homer-reading Keats who compared himself to a more hopeful observer of the heavens and to an eagle-eyed Hernán Cortés.)

Rakewell can’t help feeling a strong sense of solidarity with Keats’s sick eagle whenever the subject of the sculptures removed from the Acropolis of Athens by Lord Elgin and currently on display at the British Museum comes up. Others have laid out the arguments about what was and wasn’t legal in Ottoman-controlled Athens in the early 19th century; the debate about what is and isn’t legally possible under the British Museum Act of 1963 – and whether that should be amended – is also a live issue. No one seems to be persuading anyone on the other side of these arguments of anything.

In the long run (and perhaps sooner rather than later), Rakewell suspects that pragmatism and some kind of legal fudge will put an end to the grandstanding, on both sides, about the Parthenon marbles. But after a week in which a British prime minister seems to have cottoned on to the fact that Greece would quite like the marbles back, any amount of further idiocy is possible.

While British and Greek politicians exchange undiplomatic views, your roving correspondent finds that it helps to keep her eyes on the horizon. If there is one statesman we would really like to hear from on this subject, it’s the person who was responsible for the Acropolis complex as we know it. So: what would Pericles want? (If this seems like a silly thought-experiment, we refer you to The Frogs by Aristophanes, in which Aeschylus and Euripides compete to come back from the dead and save Athens.) Rakewell can’t pretend to know the answer, but the next time anyone brings up the glory that was Greece, it’s worth remembering that the Parthenon is the product of and a monument to Athenian imperialism, as well as a temple dedicated to the goddess Athena. After the treasury of the Athenian-led alliance known as the Delian League was moved from the island of Delos to Athens – and if Plutarch’s Life of Pericles (a very late source) is to be believed – the Parthenon-building programme was funded out of embezzling the allies’ contributions, which by this point were far from voluntary.

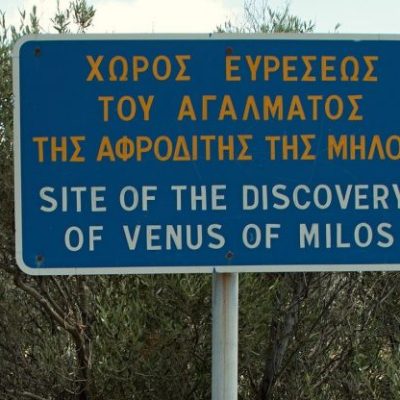

Since Rakewell strongly supports remembering the specifics of colonialism in all its forms, we suggest that for once the British stop hogging the limelight and let other historical injustices get a look in, preferably at the scene of the crime. A rehashing of all the usual arguments for and against return only takes us back to Keats and ‘a most dizzy pain, / That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude’.

Got a story for Rakewell? Get in touch at rakewell@apollomag.com or via @Rakewelltweets.

Lead image: used under Creative Commons licence (CC by NC-SA 4.0)