The most chilling lines in Paul Leni’s wonderful silent film The Man Who Laughs (1928) are spoken by a clown to his colleague Gwynplaine, the man of the title, whose smile was carved on to his face by gypsies when he was a child, freezing him into a caricature of merriment. ‘What a lucky clown you are – you don’t have to rub off your laugh.’ But Gwynplaine would give anything to wipe the smile off his own face, to show the world his sadness, and to make himself worthy of the beautiful Dea (who, being blind, has no idea how grotesque he looks).

Although Victor Hugo’s L’Homme qui rit (1869) was not one of his more successful novels, it has had a rich afterlife in adaptations for theatre, film and television, and as the source of a number of comic books – most recently a graphic novel, published in 2013, by the writer David Hine and the artist Mark Stafford. It is through comic books that it has made its most obvious mark on popular culture: Conrad Veidt’s rictus in Leni’s film inspired Bob Kane when he created the Joker as an adversary for Batman. Leni’s version was originally meant to have been directed by Raymond Bernard; it was intended as a vehicle for Lon Chaney, the ‘Man of a Thousand Faces’, and would have formed a trilogy, of sorts, with his starring roles as deformed heroes in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925). But both men withdrew from the project; instead, Universal hired Leni – whose Waxworks (1924) is regarded as one of the masterpieces of German expressionism – along with Veidt, who had starred in that film. It’s hard to see them as second best.

Mary Philbin and Conrad Veidt in The Man Who Laughs (1928)

The story begins in the England of James II (though Hugo has hazy notions of English history – he seems to have been unaware that the Glorious Revolution cut James’s reign short in 1689 – and of English nomenclature, with characters bearing the somewhat Gormenghastly names of Hardquanonne and Barkilphedro). Lord Clancharlie is put to death in the ‘Iron Lady’, and his only son Gwynplaine is sold to the Comprachicos: gypsies whose trade is turning children into profitable freaks. (Hugo invented the term, which to my ears carries a faint echo of Goya’s Caprichos.) Shortly afterwards, the king banishes the Comprachicos, and they in turn abandon young Gwynplaine on a snow-scoured Cornish dockside. Struggling through the icy night, he comes upon a dead woman, clinging to a baby girl. Gwynplaine carries the child with him to the caravan of the philosopher-showman Ursus, who takes them in, his pity awoken when he realises that the baby, Dea, is blind, and that the boy’s seeming hilarity is evidence of the tortures he has suffered.

The scene shifts: Dea and Gwynplaine are grown up, and in love. They travel the countryside with Ursus, performing plays he has written for them; Gwynplaine is now famous as the Man Who Laughs. In London, at Southwark Fair, his act is seen by the Comprachico doctor who transformed him, and by the gorgeous, capricious Duchess Josiana, who now enjoys the estates of Gwynplaine’s father. The sequence in which she watches him perform is astonishing; Gwynplaine’s frozen laugh is somehow infectious, so that the audience is reduced to tears of mirth, while in a box at the back of the theatre some unknowable passion – contempt? love? – tears at the Duchess’s breast. The audience swims before our eyes, mixing on the screen with a giant vision of Josiana, while Gwynplaine laughs and laughs.

Olga Baclanova as Duchess Josiana in The Man Who Laughs (1928). Courtesy Eureka Entertainment

It is hokum of a sort we don’t often do now – stripped of ironic distance, happily stooping to the ludicrous, unashamedly begging for our tears, gasps and sighs. Veidt is the heart of the film, expressing with eyes and shoulders the agony behind the smile, and conveying dynamism and sex despite his grotesque appearance. (The agony wasn’t feigned: he wore a painful mouthpiece, developed by the make-up artist Jack Pierce, who went on to supervise Universal’s great monsters of the following decade: Lugosi’s Dracula; Karloff’s Frankenstein.) Olga Baclanova, the Russian actor who plays Josiana, found him devastating; she spoke 40 years later of the excitement she had felt during a scene with him on a couch. She looks something like early-1980s Madonna, and exudes a similar mix of sex and ambition; in contrast, the sweetly pretty Mary Philbin, who plays Dea, seems insipid. The film also features an excellent trained dog (‘Homo, the Wolf’, which comes, I guess, from the proverb Homo homini lupus est – ‘Man is a wolf to man’), though at a climactic moment he’s replaced by a blatantly stuffed substitute.

On the new Blu-Ray disc released by Eureka Entertainment, the restored film looks good, but sounds sensational. It includes a fine modern score by the Berklee School of Music, as well as the soundtrack with which it was released in 1928 – on the cusp of the sound era. The latter includes whistling wind and roaring crowds as well as the music – a reminder that ‘silent’ film was often quite a noisy business. It’s a generous and enjoyable package. In an age when a positive attitude is seen as one of the cardinal virtues, it is also a useful reminder that a smile might not only be a mask for pain but the root of it.

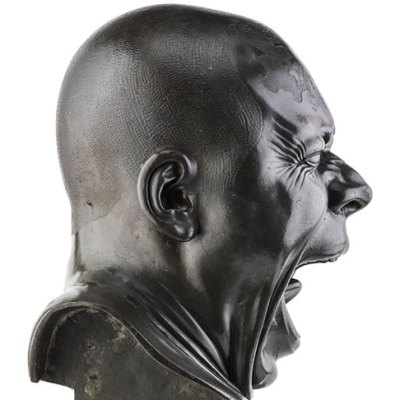

Conrad Veidt in The Man Who Laughs (1928). Courtesy Eureka Entertainment

The Man Who Laughs (1928), dir. Paul Leni, is available on Blu-Ray from Eureka Entertainment.