Tate Britain’s major retrospective is intended not only to show the full range of Paul Nash’s work, but ‘to position it within international contexts and networks’. To this end, rooms are devoted to Nash’s involvement in the short-lived modernist grouping Unit One (1933–35) and the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936; but the overarching theme remains Nash’s lifelong engagement with the English landscape. In his fragmentary autobiography, Outline (long unavailable but now reissued by Lund Humphries), Nash recalled his sudden youthful awareness in Kensington Gardens of the meaning of place: ‘there was a peculiar spacing in the disposal of trees, or it was their height in relation to these intervals, which suggested some inner design of very subtle purpose.’ This feeling for place and the arrangement of features in a landscape is more or less a constant in Nash’s work, from his sombre early watercolours of a group of pollarded elms at the bottom of the family garden at Iver Heath in Buckinghamshire, right through to the late blazing masterpieces in which his beloved Wittenham Clumps in Oxfordshire are depicted at the vernal equinox.

Equivalents for the Megaliths (1935), Paul Nash. Tate, London. © Tate

It took Nash some time to escape what he called ‘the disintegrating charm of Pre-Raphaelitism’, and one of the earliest paintings in the exhibition, Vision at Evening (1911), depicts a landscape above which a woman’s head rises like the moon, her long blue hair streaming into the sky. This picture is too self-consciously ‘poetic’, but Nash was at first doubtful about Sir William Richmond’s advice a year later that he should instead ‘go in for Nature’: ‘How would a picture of, say, three trees in a field look, with no supernatural inhabitants of the earth and sky, with no human figures, with no story?’ Greatly improved, it turned out, and human figures are mostly absent from his paintings thereafter. Nash’s original title for Outline was Genius Loci, and the landscapes of his mature paintings are imbued not with supernatural presences, but with a more rooted sense of the ancient past.

The Menin Road (1918), Paul Nash. Imperial War Museum, London. © Tate

Nash’s response to the First World War is so powerful partly because by the time he was appointed an official war artist in October 1917 any sense of place on the Western Front had been obliterated by high explosives. Both in its title and its stark depiction of churned-up mud and splintered tree trunks against the massing of blood red clouds, We Are Making a New World (1918) rebuts pre-war optimism about social and technological progress. ‘I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever,’ Nash announced in a letter from the front that might have been written by Owen or Sassoon.

The room in which this and other, less familiar war paintings are exhibited is dominated by The Menin Road (1919), a vast canvas in which grey concrete blocks and brown curls of corrugated iron litter a desolate landscape, and a rusted petrol can and a discarded tin helmet bob on the surface of a flooded shell-hole. The appearance of alien objects into more peaceful landscapes would become a frequent motif in Nash’s paintings, perhaps also inspired by the Martello towers that loom over the houses in Dymchurch, where he spent long periods from 1919 to 1922. Nash’s series of images of the sea wall at Dymchurch are rightly celebrated and well represented here; but even more striking is one of the beautiful paintings he did of the huge concrete cube that appears to have been arbitrarily dumped beside Dymchurch steps.

Nash’s work during the Unit One period moves towards abstraction, but pictures such as Stone Tree (1934), painted after visiting Avebury, make use of recognisably organic forms and are very different from the (largely inferior) work by other Unit One artists instructively hung alongside them. And while interiors such as Northern Adventure (1929), and more abstract works like Voyages of the Moon (1934–37) reflect Unit One’s modernist aesthetic, their design also look back to places Nash knew in his youth: the light-filled morning room at Iver Heath, where the interior seemed ‘inseparable from the scene outside’, and William Rothenstein’s house in Hampstead where Nash observed ‘the austere beauty of its lines and intelligently considered spaces, its colours in a low key’.

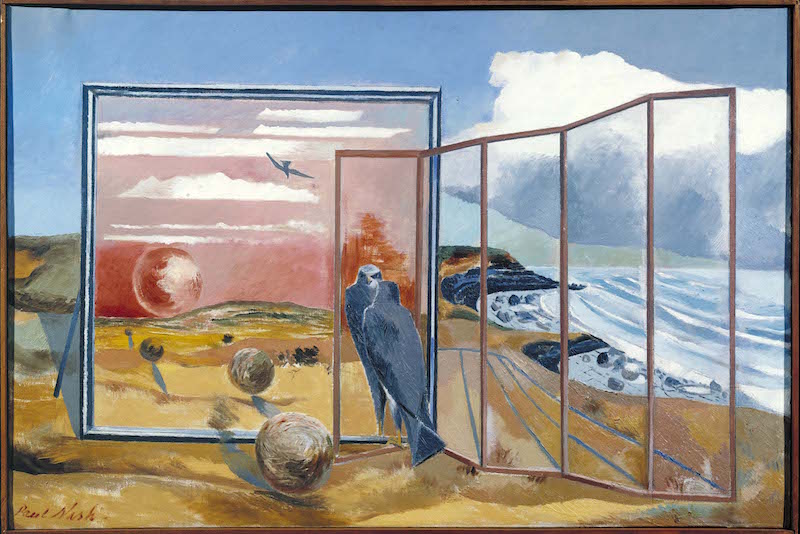

Landscape from a Dream (1936–38), Paul Nash. Tate, London. © Tate

Similarly, although the European influence of painters such as Giorgio de Chirico is clearly apparent in such works as Nostalgic Landscape (1923–38), Nash’s own surrealism owed a good deal to the oddities he observed in the English scene. The curious Objects in a Field (1936), for example, depicts a real concrete trough Nash had discovered and photographed on farmland. Tennis balls are among the ‘found objects’ Nash included in several works, but the outsize one in Event on the Downs (1934) has something about it of the Great Globe, a huge sphere of Portland stone at Swanage, where he had spent time that year. The town would later become his base while he worked on the Shell Guide to Dorset (1936), in which his sense of the English surreal was given full rein.

Event on the Downs (1934), Paul Nash. Government Art Collection

The Second World War provided further examples of the intrusion of unexpected objects into the English landscape, and Nash’s ravishing watercolours of German bombers shot out of their element to lie in woods and fields are among his most eloquent works. Five examples are hung alongside Totes Meer (1940–41), perhaps the most famous painting of the war. It was inspired by Cowley Dump; Nash’s photographs of the dump and a film of him making sketches there are also on display in this broadly conceived and very enjoyable exhibition. Paintings are generously hung to give them breathing space and vitrines contain books, letters, and three-dimensional artworks. Taken as a whole this retrospective makes a persuasive case for Nash as one of the last century’s truly great English artists.

‘Paul Nash’ is at Tate Britain, London, until 5 March 2017.

From the January issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.