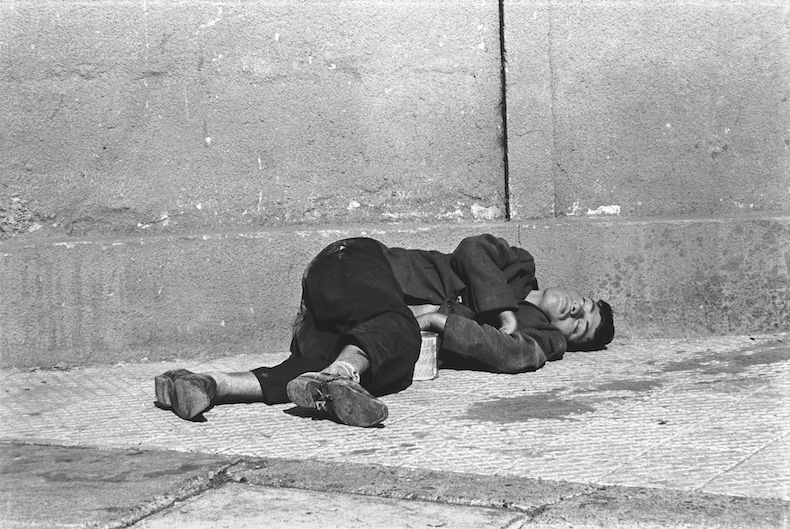

‘Paz Errázuriz: Dare to Look’ begins with Los Dormidos (‘The Sleeping’), a series the Chilean photographer made in 1979–80 at the height of the Pinochet dictatorship, capturing people asleep in Santiago’s public parks and streets. There is nothing grandiose about these pictures. One or two have a spooky hint of crime scene; most are coolly, even drably observational, though puzzling for a reason you can’t quite articulate, as if there were something else at work.

There was, of course. When simply being on the street with a camera was subversive, obfuscation and allusion were Errázuriz’s only recourse. The sleepers are a metaphor for political listlessness, a way of visualising that despite ‘the silence and immense anxiety […] the dictatorship that lied and brutalised […] the street was also asleep, and didn’t rebel until the late 1980s.’

Errázuriz had been awake for years by then. Within days of the violent and bloody 1973 coup d’état, her home was raided by armed soldiers. She was 30 then, a primary school teacher with two young children and photography for a hobby. Fired from her job by the junta for belonging to a union, photography became everything: ‘The protected little Catholic girl with a privileged upbringing […] finally began to see,’ she said. ‘And together with her naivety she discovered the darkness, the forgotten, the destroyed – right there, at every step.’

There are upwards of 170 photographs on display at MK Gallery, Milton Keynes. The exhibition is Errázuriz’s first solo presentation in the UK and its curatorial arc shows brilliantly not just her fierce intentions, but how quickly she warmed to what the camera could do. Just feet – and scant years – from Los Dormidos is Personas (‘People’), a strange and poetic series in which Errázuriz insinuated the disparities of Chilean society. El Caminante (‘The Walker’; 1987), for instance, captures the contorted stagger of a perhaps drunk, more probably disabled man in smart but stained clothing; Regias, Santiago (‘Royals, Santiago’; 1988) fixes four women at a cocktail gala in perpetual braying conversation, their lipsticked mouths twisted into an extraordinary, aberrant geometry.

Indeed, Errázuriz is acutely attuned to the body’s tells. In De a dos (Tango) (‘In Pairs (Tango)’) – elderly couples dancing in the clubs of Recoleta – elbows, foreheads, smiles and gestures loom from the darkness in a way that is almost abstract. Hands – clasped, pained, fidgety, needy – are a constant. A great many of the works in this exhibition feature them. They float in the space like half-comprehended emotions, so alive you can conjure the feel of the flesh.

The way life inscribes itself on that flesh is a recurring theme, forensically explored in Cuerpos (‘Bodies’; 2002) – studio portraits of elderly men and women proudly displaying their naked bodies – and more gently in Un Cierto Tiempo (‘A Certain Time’; 2004), a six-minute slideshow conveying the evanescence of youth in monthly photographs of Errázuriz’s growing son.

The brutality of Pinochet’s 17-year rule (more than 3,000 people ‘disappeared’ or killed; some 38,000 imprisoned and tortured) is mostly present in Errázuriz’s work as a subliminal hum rather than directly. She made a tentative foray into photojournalism in the early 1980s, but overwhelmingly turned away from that fleeting, furtive type of encounter towards something markedly involved.

Indeed, most of the series here were the outcome of a trust gently won over time, particularly among the communities that were corralled and rendered invisible under Pinochet’s rule. Sex workers, the homeless, queer people, the elderly and the indigenous Kawésqar in Chilean Patagonia.

In 1978, pursuing rumours that political prisoners were being held in psychiatric institutions, Errázuriz began visiting those places to look for her disappeared friends. That search was futile, but the abject conditions she found inside across the board struck her so deeply that some years later she obtained permission to photograph at the Philippe Pinel psychiatric hospital, 100km north of Santiago.

El Infarto del Alma (‘Heart Attack of the Soul’; 1994) is one of the most affecting series here: tender portraits of the men and women who defied their hellish circumstances – many were listed in the hospital records as ‘NN’, meaning No Name – to fall in love. ‘They liked it very much, those patients, when they learned that I had noticed they were couples,’ Errázuriz says, in a documentary playing nearby.

Returning in 1999, she made photographs of women patients in the shower block. These are powerful, difficult images: the walls clammy and peeling, the women bony and fragile, childlike in their resignation. Errázuriz admitted she was ‘terrified’ by the scenes and wrestled with her conscience for years over whether to exhibit them. Improvements to care were made when she did.

There’s a quote from Errázuriz on the wall next to these photographs. In paraphrase, it says that however unsettling these and other bodies in her work may be, she has learned to find in them an ‘extraordinary’ beauty. ‘Whenever you insert that intention or emphasis,’ she adds, ‘you can reflect something wonderful. It depends on how you look at it. What attention you give it.’

Apply that same attention, or intention, and you sense the pictures shifting and resettling, the subjects engaging you in silent conversation. It’s hard to pin down what magic is at work, but you have to walk back through the exhibition to reach the exit, and it was a subtly different set of photographs I saw the second time.

‘Paz Errázuriz: Dare to Look’ is at MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, until 5 October.