On a balmy mid-September afternoon, seagulls hover in the turquoise skies above the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, adding a fitting nautical touch to a ceremony in progress on the brick-paved streets. Crowds gather around a massive iron anchor, salvaged from a 19th-century ship and donated a century ago to PEM (as the museum is widely known). Weighing about two tons, it has just been repaired and repainted offsite in anticipation of the imminent opening of a $125m expansion to the museum. A crane hoists the anchor back on to its long-time stone pedestal near a museum doorway, while journalists, museum staff, curiosity seekers and local politicians document the scene with cell phones aloft. I hold my breath as workers grab at straps to steady the anchor in transit. The crane’s strained cable and load nearly brush against the hewn-granite facade of the museum’s original wing, the East India Marine Hall. It was built in the 1820s as a meeting place and exhibition venue by Salem’s merchants, who globetrotted while collecting just about everything, from ostrich eggs to kayaks, tattooing tools and outerwear made of sea-lion intestine.

Jacket-cape (c. 1820), Aleutian Islands, Alaska. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem

As the anchor’s safe landing sets off cheers, the museum’s Dublin-born director, Brian Kennedy, gives a speech about the symbolism of getting the anchor ‘back in shipshape’ as the institution begins ‘a new era’; he’s a newcomer to PEM himself, having taken over in July upon the retirement of long-time director Dan Monroe. The granite-clad addition to the building, designed by Ennead Architects in New York, is slightly angled back from the street. ‘The facade of the new wing bows gently in reverence’ to the 1820s hall, Kennedy says. The expanded museum, he adds, embodies some of the founders’ mottoes: ‘Be bold. Be curious.’

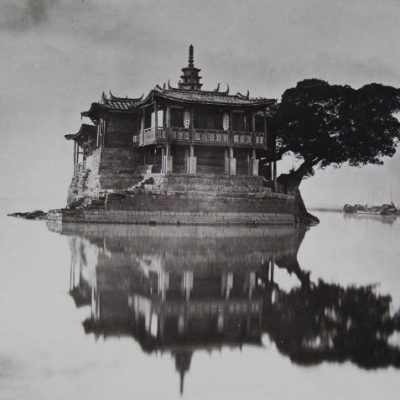

The Peabody Essex Museum has sprouted new wings again and again since the region’s ship captains first turned their hall’s display cases into what they called a ‘cabinet of natural and artificial curiosities’. The institution ranks as America’s longest continuously operating museum. And in a modest coastal community of about 43,000 people, it amounts to a very large cultural fish. Kennedy’s team of 250 people oversees a nine-figure endowment and two dozen scattered structures, in addition to the main campus in downtown Salem. The last major expansion phase, designed by the architect Moshe Safdie, opened in 2003, with brick pavilions and an atrium capped in glass vaults that look like upside-down ship hulls. Ennead has added 15,000 square feet of exhibition space to the existing 125,000 square feet of galleries. The collections span continents and millennia, but are particularly rich in the maritime and Asian trade realms. One highlight, acquired in the early 2000s, is an entire 18th-century house called Yin Yu Tang from south-east China, which was dismantled and transplanted to Salem complete with Mao posters and rustic kitchen cookware.

Tureen (1740–50), China. Photo: Dennis Helmar; © Peabody Essex Museum, Salem

My September preview lasts eight hours, a marathon of cross-cultural enlightenment (and I would have stayed longer if they’d let me). Kennedy sets the tone for my journey in the morning, observing that the collections are ‘very closely allied with the history of the place’. Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, PEM’s deputy director, adds that in the current and upcoming exhibitions, ‘The story of Salem is there in intriguing, elegant and inspiring ways, and in some cases really challenging ways.’ Surprising juxtapositions of materials and eras, selected from growing holdings of 1.8 million objects and artworks, are installed at every turn: ‘I really encouraged the curators to go shopping across the collection,’ she says.

Salem became infamous in the 1690s, when its fledgling colonial government imprisoned dozens of people on witchcraft charges (20 locals were eventually executed by hanging or crushing). Hundreds of thousands of tourists now descend on the town around Halloween time; some are wearing bloodied costumes and seeking ghoulish thrills, and others are deepening their knowledge of historical traumas, demonisation, mass hysteria and mob justice. Local businesspeople have created related attractions such as dungeon theme parks, the Witch City Mall and a Harry Potter-esque shop labelled ‘Wynotts Makers of Fine Wands Since 1692’. (PEM has largely avoided witch kitsch, although some shows have been targeted at the autumn crowds – in late 2017, for instance, it borrowed science-fiction and horror-movie posters from the heavy-metal guitarist Kirk Hammett.) The town is also haunted by the sources of the fortunes of some of its first shipping tycoons, which include enslaved people and opium.

Crowninshield’s Wharf (1806), George Ropes. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem

The East India Marine Society, the original kernel of PEM, was founded in Salem in 1799, when local wharves ranked among the busiest in the world. Society membership required proof of having ‘navigated the seas beyond the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn’ while serving as a ship master or supercargo (that is, an owner’s agent). The organisation set out to give aid to the impoverished families of deceased members while also sharing maps, foreign commerce records, logbooks and other navigational research materials and creating displays of exotic artefacts. As early as 1804, the Evening Post in New York praised the museum’s acquisitions from ‘remote nations and Islands’ as ‘a very extensive, and valuable collection, and arranged with taste’. The granite-clad exhibition hall filled up as batches of donations arrived, despite the local economy’s shrinkage – New York and Boston gradually siphoned away business from Salem’s ports. In 1823, Sir Isaac Coffin, a Boston-born British politician who’d commanded British naval ships, gave the society about 100 medals portraying ‘Kings, Queens, Statesmen, Warriors, Scholars, and Moralists’. By the 1840s, the displays also included a Hawaiian deity named Ku, seashells, tiger and lynx pelts, whale skeletons, life-size statues of Middle Eastern and Asian merchants and ‘implements of war and peace used by demi-civilized nations abroad’. From the 1860s onwards, the society was folded into a series of other scholarly groups including scientific and historical societies. There’s been phase after phase of institutional consolidation over the years, most recently in the 1990s, when the Peabody Museum of Salem and the Essex Institute joined forces as PEM. (Major financial backing has come from, among other sources, the philanthropists and Old Master paintings collectors Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo; the Johnson family, billionaire owners of Fidelity Investments in Boston; and Fidelity executive Peter Lynch.)

Safdie’s wings from 2003 created multiple entry paths to spaces for rotating shows and highlights of the permanent collection such as a bejewelled Qing dynasty feather headdress and a Chinese porcelain cup on a German metalsmith’s gilded-silver mounts. Panoramas of Asian harbours hang alongside glimpses of the Yin Yu Tang house’s flared roofs. Ennead’s addition, with raised walkways along an exposed brick side wall of the East India Marine Hall, is likewise intended to inspire wanderings. ‘It’s not meant to be prescriptive,’ Hartigan says. ‘Hopefully people will get lost, in the best sense of the word.’ She uses the phrase ‘memory palace’ to describe her ideal for PEM’s effect on its audience, but then quickly corrects herself: ‘“Palace” sounds too elitist.’

Headdress (18th century), Qing dynasty, China. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem

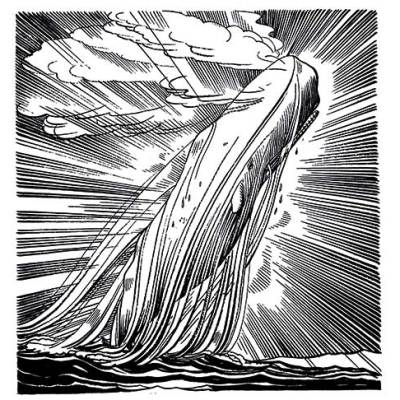

Daniel Finamore, the curator of maritime art and history, tells me that he aims to attract visitors who think they are not interested in the oceangoing experience. ‘Breaking that mould of what people assume “maritime” to be is critically important to us,’ he says. A blue-eyed female ship figurehead, her carved surfaces singed and battered over two centuries of use, overlooks maritime galleries with soundtracks of wind and crashing waves. A mahogany model of the Queen Elizabeth ocean liner, which the Cunard Line commissioned for their Manhattan offices in the 1940s, measures 22 feet long. A display case is devoted to unglamorous-looking bits of commodities, like sandalwood, ginseng and guano, for which traders fought and died. A Fijian tattooing stick on view was donated by a Salem merchant in 1802. Contemporary sculptor Valerie Hegarty’s Shipwrecked Armoire with Barnacles, fashioned out of foamboard in 2012, suggests the folly of carrying anything valuable in your luggage. Six paintings by the marine artist John Cleveley the Elder from 1759 depict the Luxborough Galley, a British slave ship destroyed by fire. The few survivors among the crew eventually resorted to cannibalism aboard a makeshift sailing boat, its sail stitched together from squares of the men’s clothes. A not unpleasant spicy smell wafts through the galleries, from a tarry wood block that Boston artisans used in the 1790s while building the USS Constitution, a naval frigate now serving as a museum in Boston. The goal, Finamore says, is to ‘engage people at a very gut level’.

In the Fashion and Design galleries, provocative questions have been posted on the walls. Visitors are asked to ponder, for instance, ‘How did you style yourself today?’ and ‘How do you design your world?’ amid arrays of shoes, fabrics, garments and related artefacts. ‘We really wanted people to embrace their inner designer,’ Petra Slinkard, the curator of fashion and textiles, tells me. Perhaps viewers will imagine themselves riding wooden skateboards that Rico Lanaat’ Worl designed in 2014, using outlines of Tlingit bird motifs. Or maybe they will wonder what it’s like to shakily tower over people in Sebastian Errazuriz’ 3D-printed plastic ‘Heartbreaker’ red stiletto, pierced by an arrow. Slinkard’s team has also exposed the hidden costs and paradoxes of luxury. A crude black leather boot, manufactured just before the Civil War in largely abolitionist Massachusetts, was meant to be worn by an enslaved person in the American South. Tiny silk sheaths were colourfully embroidered for the bound feet of aristocratic Chinese women. Male mannequins are dressed for bloody conflicts: a Salem infantryman’s gilt-braid-trimmed uniform was worn in battles of the 1810s against the British, a Native American’s beaded leather shirt was donned in wartime around 1840. The galleries have equally evocative furnishings on the pedestals. Could a Chinese courtesan hobbling in silk shoes have found some solace retreating to a cylindrical satinwood ‘moon bed’ that artisans carved in the 1870s, or resting her head on a 19th-century ‘summer pillow’ made of woven bamboo?

Cup (c. 1570–1610), Jingzheden, China and Nuremberg, Germany. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem

One room in the new Asian Export galleries is lined in Chinese wallpaper, painted around 1800, that depicts hundreds of Chinese labourers (plus a few Western traders). The panoramic setting is Canton’s creamy row of colonnaded buildings, where foreigners were allowed. This slim crescent at the rim of an empire ‘was one of the most cosmopolitan parts of the world,’ Karina H. Corrigan, the curator of Asian export art, tells me. The mulberry paper wallcovering was made for James Drummond, a Scottish leader of the British East India Company who eventually shipped it home to Strathallan Castle in Perthshire. The exhibition soundtrack combines Scottish rain, wind and bagpipes with Canton’s babel of importers’ and exporters’ music and languages. The overheard negotiations are not quite intelligible, ‘not really in any kind of official dialogue’, Corrigan says.

Portrait of Harriet Low (1833), George Chinnery. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem. Photo: Mark Sexton

Her exhibition honours steely nerves as well. A painting by George Chinnery from 1833 depicts tousle-haired Harriet Low, a Salemite who dressed in drag to sneak into Chinese territory where all foreign women were forbidden. (A furore ensued when she was unmasked.) There’s obsession, heartbreak and greed on view, too. Augustus the Strong’s blue-and-white Chinese porcelain vase from the 1710s, measuring three feet tall, was part of a set that cost him an entire regiment in a trade with Prussian royals. How horrified he would have been to see the Dutch sculptor Bouke de Vries’s glass-walled Memory Vessel (2015), packed with shards of an 18th-century Chinese blue-and-white porcelain jar. A new short film acknowledges that Salemites long considered opium an ‘honorable and legitimate’ product to market and that therein lie some roots of the contemporary opioid crisis. Images of smoke, flames and blood course through the film, which quotes 19th-century seafarers’ pro-drug writings and Chinese official protests against ‘the spread of the poison’. Corrigan says that the connection between opium and some of PEM’s founders is ‘a story that we have not historically talked about’.

Amid the powerful evidence of long-ago misdeeds, PEM has created moments of great beauty. Ennead’s new atrium, visible from the street, is dominated by a 19th-century breadfruit wood carving of that Hawaiian deity, Ku. A symbol of prosperity and strength, he has been displayed in Salem on and off since he arrived in the 1840s. By the 1820s, Hawaiian leaders were destroying such figures, to root out old religious practices. He has only two surviving counterparts, one at the British Museum and the other at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. (The three were briefly reunited in Honolulu in 2010.) Ku’s braided hair trails down his back, and he bares his fangs. Some visitors with origins in Pacific islands leave talismanic offerings for him (I saw three enigmatic little bundles of brown and white cloth at his feet). ‘They bring greetings from their ancestors,’ says Karen Kramer, PEM’s curator of Native American and Oceanic art and culture. She adds, ‘He’s facing west, home, toward Hawaii.’

Statue of Ku (early 29th century), Hawaii. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem. Photo: Mark Sexton

In the next few years, PEM will devote galleries in the Safdie wing to its Native American holdings and Americana. Kramer is working with the Navajo photographer Will Wilson, who uses antique equipment to create tintypes of indigenous community members. He will make high-tech ‘talking tintypes’, portraying descendants of Salem’s Wampanoag tribe members and recording their stories of resilience dating back to the first arrival of Europeans. ‘We can explore this place from their perspective,’ Kramer says.

Kennedy is considering ways to further animate the building’s exterior, ‘a really elegant series of architectural developments in a row’, and to engage with a broader range of constituents including Halloween tourists. He hopes to avoid complacency, he says. ‘We’re going to attempt to turn ourselves inside out,’ he adds, before heading off to meet the Chinese artist Gu Wenda, known for large-scale installations of paper lanterns and giant calligraphy painted with green algae.

A mesmerising illuminated installation is almost ready during my preview. The artist Charles Sandison is fine-tuning his computer pixel projections that cover every surface inside the East India Marine Hall’s gallery. Streams of white and red light, some containing text fragments excerpted from Salemites’ logbooks, transfigure the male and female ship figureheads projecting from the walls and the empty original display cases over the fireplaces. Visitors are welcome to just flop down on the floor, Sandison says. ‘What I’d like,’ he adds, ‘is that they become neurally connected to this digital snow-globe.’ A line of handwritten prose glows over my head: ‘Friday January 29th 1779.’ I wonder what the Salem cargo holds were carrying that day, and where the winds were taking them.

From the November 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.