In the galleries of Waddington Custot in London, four sea battles rage on aged wooden galleons. The combatants are mostly plastic, an assortment of commercially produced figurines, identified (by the titles) as ‘Cowboys and Indians’, ‘Disney princesses’, ‘Soldiers versus characters from Disney’ and ‘Knights versus People being frightened in “B movies”’. They have been arranged by the playful hand of Britain’s most prominent Pop artist, Peter Blake.

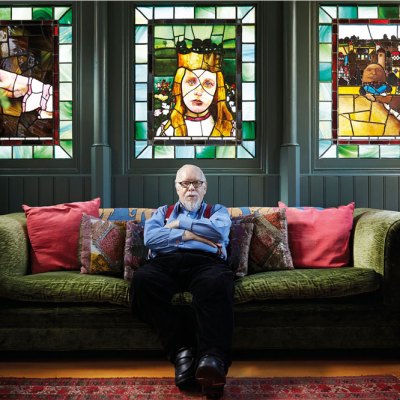

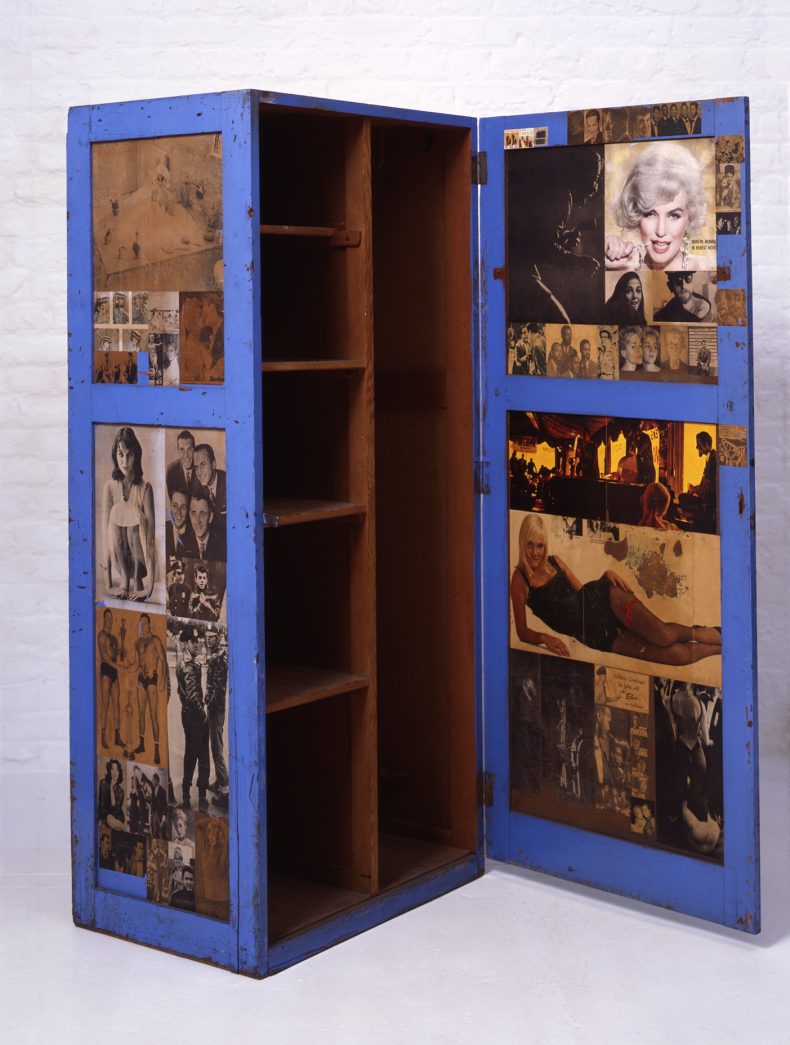

This is the first exhibition in more than a decade to focus on Blake’s sculpture. Though to many this will be a less familiar aspect of his work, it has been a remarkably consistent interest of the artist’s throughout his long career: Locker was first exhibited in 1959, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. A found RAF locker covered in pin-ups, the piece combines sculpture with collage, the medium with which Blake is generally more associated. Pin-ups continue to abound in his more recent work, along with other favourite themes: Mickey Mouse, Snow White and the visual language of Boy’s Own. Meanwhile, his latest collages – such as the Larousse series (2023–24), derived in part from the eponymous French illustrated dictionary – continue his interest in Victoriana, uniting figures and objects under loosely thematic titles, many suggestive of carnival or holiday (‘Parade’, ‘Picnic’, ‘Circus’).

Locker (1959), Peter Blake. Courtesy Peter Blake and Waddington Custot; © the artist

From one perspective, these assemblages flatten Blake’s source material. High culture merges slyly with low, and almost anything is legitimate material for pillage and plunder. Indeed, it is striking how many of these works include doggedly light-hearted references to historical and imperial conquest, often refracted through the lens of Americana or Victoriana – Cowboys and Indians, in particular, are everywhere (including at sea). Meanwhile, Beethoven stands by a climbing frame in The Performance Artist (from Incidents from a Sculpture Park) (1983), and a series from 2023 juxtaposes William Hogarth with Elvis Presley and lettering and images from 20th-century comics and magazines.

However, these are never entirely neutral reference points. Hogarth too was preoccupied with the creative possibilities of juxtaposition (many of the prints selected, notably Gin Lane and France, are pendants without their partners). Time Smoking a Picture, his dig at connoisseurs who value paintings primarily for the muddy appearance of aged varnish, is already a picture within a picture. Here it juts up against a frenetic capitalised ‘WHAM’, and Donald Duck playing a guitar. The patina that now suffuses Hogarth’s work (itself culled from copies and reproductions) contrasts with bold colour pops of green, yellow, red and electric blue.

Dodo, from the Larousse series (2023) by Peter Blake. Courtesy Peter Blake and Waddington Custot; © the artist

Blake’s distinctive visual sensibility reflects his own status as a collector of ephemera. Several works, including the encyclopaedic Larousse series, engage with the significance and purpose of collecting itself, whether in two dimensions or three. Museum of Black & White 12 (in homage to Mark Dion), from 2008–10, brings together disparate monochromatic objects – a football, a doll, a large letter E, a phrenological head. Linked only by their colour (and their inclusion in the artwork), these black and white objects recall the black and white newsprint and photography used in so many of Blake’s works on paper. The titular tribute to the conceptual artist Mark Dion, whose work is often concerned with taxonomic systems, highlights the status of the museum as a space (like collage) in which meaning and stories are made through strategic and selective accumulation and juxtaposition. Meanwhile, Shrine for Elvis (Black & White) (2003), a set of publicity stills framing a cluster of Elvis-branded memorabilia, presents itself as a prized personal collection. Similarly, once pasted on to Locker, Blake’s pin-up collage acquires another layer of meaning as the implied work of an individual: presumably an RAF pilot, with a love of Brigitte Bardot and bodybuilding and an eye for pattern.

At the same time, the appeal of Blake’s work, much of which also has a captivating physical presence, lies largely in its rejection of any single narrative in favour of a proliferation of speculative anecdotes, which will differ from viewer to viewer and viewing to viewing. Unlike many depictions of naval warfare, the works in the Sea Battle series (2010) do not concern themselves with the rivalry of nations, but with trivial and nonsensical questions – such as where are the Disney princesses going, en masse? This determined focus on the anecdotal may prevent Blake’s work ever claiming to serious intellectual heft. Nonetheless, it remains as delightful as an anecdote can be.

Man Meeting a Tiger on a Bridge (1960), Peter Blake. Courtesy Peter Blake and Waddington Custot; © the artist

‘Peter Blake: Sculpture and Other Matters’ is at Waddington Custot, London, until 13 April.