For an artist interested in capturing life ‘hot off the griddle’ (as the painter Alice Neel once put it), there are only so many places one can seek inspiration. Once friends and family have posed for you, you’ve used up your photos and your imagination is failing, one of the only remaining reliable sources of raw spirit is the street. Sure, you can hire a model or draw on pictures from popular culture, but there’s often something a bit contrived about the relationship between such subjects and the artist. To depict life as it comes naturally, unpasteurised, one must turn to the public domain.

To curate an exhibition on the subject, Gagosian Gallery in New York has handed over the reins to Peter Doig. The Scottish artist is best known for cinematic paintings of disquieting imaginary scenes, often set in remote, public places such as the forest or at sea, recalling his childhood in Canada. Still, he is no stranger to urban living, splitting his time between London and Port of Spain in Trinidad.

The Delights of the Poet (1912), Giorgio de Chirico. Esther Grether Family Collection. Photo: Robert Bayer, Bildpunkt; © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

There are a number of ways an artist could go about painting the street. From Romare Bearden’s choppy, jazzy collages to Reginald Marsh’s bawdy, Rubenesque paintings of Coney Island Beach, there’s a rich and varied history of painters of urban life. The Gagosian exhibition includes work by 17 different artists, but since it presents Peter Doig’s view of the subject, it feels more like a single statement followed by silent nods of approval.

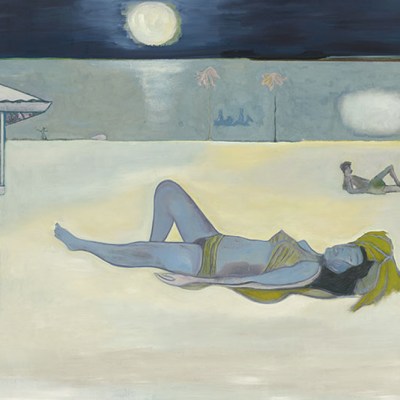

The unifying factor – perhaps even more so than the stated subject matter – is Doig’s own taste. (And there are quite a few works, such as Vija Celmins’s painting of eggs in a pan, that seem to have nothing to do with the street.) It’s not surprising that Doig seems more interested in the painterly aspects of the works on display. There’s a consistent gloomy colour palette of orange, green and blue – reminiscent of Edvard Munch, a painter who has clearly influenced Doig. As in the work of Munch, there is much deliberate mark-making here – from Beauford Delaney’s hurried impasto to Satoshi Kojima’s subtle, illusionistic finish. Many of the paintings are quite large. They feel human-oriented, scaled almost as if the viewer could step right into the street of the painting. Lotte Maiwald’s canvas even extends from the wall on to the floor, making the jobs of the guards – who need to tell viewers not to step on it – a little harder.

..den Fehdehandschuh hinwerfen (2021), Lotte Maiwald. Photo: Maris Hutchinson; courtesy Gagosian; © Lottie Maiwald

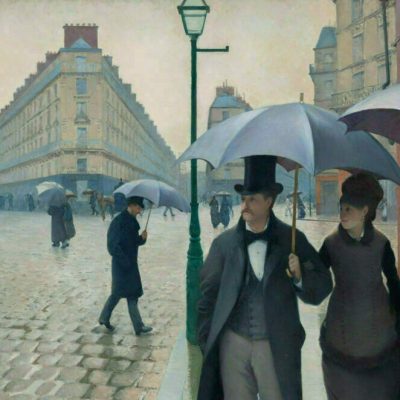

But, even if one could enter the worlds of these paintings, I’m not sure anyone would particularly like to. Most of the streets depicted here are cold and uninviting. De Chirico’s The Delights of the Poet (1912) shows an open space next to two buildings cast in golden hour sunshine, with just one soul standing in the distance. There’s an uneasy tension here, prompting the question: where did everyone go? In Jean Hélion’s Grande scène journalière (1948), two men walk towards each other, completely unaware of the other’s presence due to the newspapers, constructed like Frank Gehry buildings, that they hold in front of their faces.

For Peter Doig, it seems that the street – rather than offering our last hope to connect with one another – highlights our separation. In turn, this distance seems to breed apathy and even violence. Among the paintings of empty corners and silent plazas, there are pockets of brutality peppered throughout the gallery. The most terrifying, and possibly the best painting in the whole show, is Max Beckmann’s hellscape Hölle Der Vögel (1937–38): a dungeon of demons torturing a man bound by his feet and wrists.

The Street (1933), Balthus. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York; © 2024 Balthus/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

The relationship between disconnection and cruelty seems to be the subject of Balthus’s painting The Street (1933), which is positioned as the centrepiece of the exhibition. Pedestrians in Paris pass each other without any contact, while ignoring a sexual assault taking place in the corner of the canvas – the composition so blasé you might miss the shocking detail. When this painting was exhibited in Balthus’s first solo show at the age of 26, it was hung among many other similarly enigmatic, slightly off-putting pictures. But he kept one painting, The Guitar Lesson, covered by a curtain in a back room because he thought it was too severe and scandalous for the general public. It portrays a teacher, with her female pupil laid across her lap like a guitar, pulling down on the young girl’s hair and playing with her genitals as if they were strings. At Gagosian, some of the most disturbing paintings in this show are also kept in a back room: Doig’s own small, repetitive sketches of violent acts, such as lions fighting (made as a study for a larger painting, also on display) and one man pinning another to the floor in an act of domination. This room feels like the source of a subliminal anger that permeates the rest of the show. These pictures are done in quick marks on cheap materials such as cardboard, emblazoned in neon pink, yellow, orange, and red; I can almost imagine Doig drawing these hastily under the table so no one could see.

Lions (Ghost) (2024), Peter Doig. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian; © Peter Doig

Doig can be coy when asked about the meaning of his paintings. So was Balthus. When a biographer asked him about the significance of The Street, Balthus said it was simply meant to celebrate the wonders of daily existence. There are many paintings that celebrate the pleasant wonders of the street. None of them are in this austere yet troubling exhibition.

‘The Street: Curated by Peter Doig’, is at Gagosian, New York, until 18 December.