The novelist Philip Roth and the painter Philip Guston commiserated in upstate New York in the summer of 1971, bemoaning the controversial presidency of Richard Nixon. That year, Roth would publish his satire of the Nixon presidency, Our Gang, of which he shared a selection from early drafts with Guston, who began producing a slew of drawings also mocking the divisive American leader and his cronies. In today’s similarly fraught political climate, Hauser & Wirth on New York’s 22nd Street is exhibiting ‘Philip Guston: Laughter in the Dark, Drawings from 1971 & 1975’. The exhibition features around 180 works, including Guston’s Poor Richard series (1980) alongside related drawings and paintings that have never before been shown publicly together.

Untitled (Poor Richard) (1971), Philip Guston. Image © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Seventy-odd drawings were published after Guston’s death in the book Philip Guston’s Poor Richard, which chronicled the life of Nixon from childhood through to his famous visit to China in 1972. These satirical drawings came after Guston’s notorious stylistic break with Abstract Expressionism in the mid 1960s, when he moved towards his recognisably crude figurations of thick, cartoonish men and hooded Klansmen. Guston agonised over the state of global politics, lamenting the horrors of the Vietnam War and questioning his role as an artist in such troubled times.

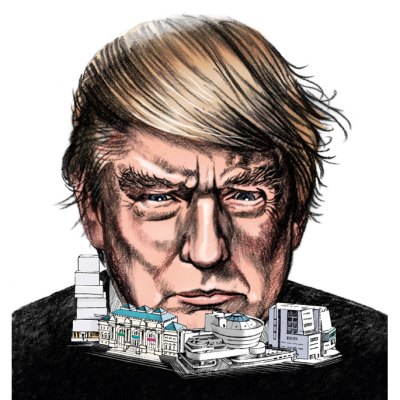

The exhibition encompasses the entire second floor of the gallery. The drawings mostly follow the trajectory of Nixon’s career: Guston depicts young Nixon as a beady-eyed man with a long nose, at times sporting a five-o-clock shadow. As he ages, Nixon’s face becomes emphatically more phallic, the long nose protruding and his cheeks heavy and sagging. As he enters the political stage, Nixon is shown surrounded by those on whom he most depends: national security advisor Henry Kissinger (a pair of glasses), attorney general John Mitchell (a pipe), and vice president Spiro Agnew (a set of golf clubs).

Untitled (Poor Richard) (1971), Philip Guston. Image © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

For visitors like me, who did not come of age during Nixon’s tumultuous administration, the gallery has provided a timeline. Beginning with Nixon’s birth in 1913 and concluding with his death in 1994, it highlights the major events defining his truncated regime, which ended with his resignation in 1974 after the Watergate scandal broke and the White House tapes were released. The chronology provides helpful context for most of the artworks, but it is rewarding to independently decipher Guston’s pictorial system to see which of Nixon’s schemes made Guston fume and vent. In 1975 he began drawing the Phlebitis Series, illustrating the departing president as a grotesque figure. As Nixon tows a heavily deformed and bandaged leg behind him, he leaves a questionable legacy and an obvious burden for his successor.

Musa Mayer, Guston’s daughter, expedited the hanging of the show, which was pulled together in a handful of weeks with the support of the Guston Foundation and curator Sally Radic. Since the latest election results have been announced, the material seems particularly sharp and cogent. Recent articles have both announced Donald Trump as Nixon’s heir apparent and decried the comparison, but there is no denying that the two characters were and are terribly self-conscious and narcissistic individuals in uncharted media landscapes. As the dangerous inevitability of a Trump presidency settles into our collective consciousness, artists should question the status quo and raise their doubts, providing commentary and criticism for these troubled times. Guston might have had reservations about the legitimacy of his practice, but he channeled his frustration and fear into generating a body of work that has both historic specificity and biting, contemporary relevance.

‘Philip Guston: Laughter in the Dark, Drawings from 1971 & 1975’ is on view at Hauser & Wirth, 22nd Street, New York until 28 January 2017. It moves to Hauser & Wirth London from 19 May–29 July 2017.