It’s every historian’s dream to track down an untouched archive. That is exactly what Kieron Connell – a researcher at the University of Birmingham – experienced in 2014 when, after months of searching, he received an email from a photographer: ‘I would love it if you could take over the collection of all my images about Balsall Heath’.

Janet Mendelsohn – the author of the email – spent the years 1967–69 in Birmingham as a visiting student at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS), the 50-year-old organisation that Connell had been researching. Mendelsohn’s academic objectives while there were radical: her aim was to observe and photograph the life of a working class, multi-ethnic community in the city’s Balsall Heath district, which at the time was at the centre of a wave of national concern about ‘vice’, fed by salacious tabloid journalism and ugly prejudices.

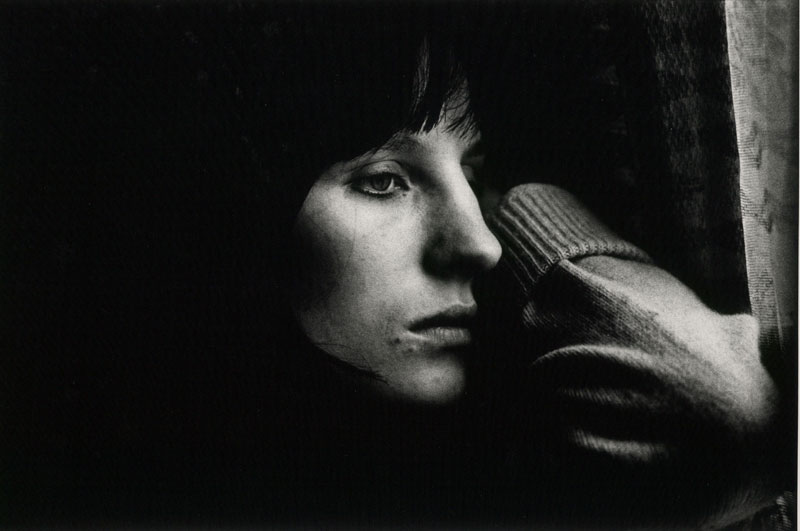

Kathleen hanging out (c. 1968), Janet Mendelsohn. Courtesy Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham

Recognising the photographs’ value, both aesthetic and historical, the University of Birmingham has arranged for a selection, entitled ‘Varna Road’, to be displayed at the Ikon gallery. Ahead of the exhibition I spoke to Professor Matthew Hilton, who led the research project into the CCCS, about the context of Mendelsohn’s photos, and the challenges of presenting images that peer into a murky world marked by dilapidation, want and exploitation.

Mendelsohn’s monochrome images are striking: despite the bleak surroundings they have a wide-eyed quality that captures the details of her subject’s lives. They are stunning both aesthetically and sociologically, and as Hilton tells me, ‘there’s a certain intimacy to them’. The selected images focus on one sex worker ‘Kathleen’*, who Mendelsohn photographs in a ‘humanising’ way that Hilton finds ‘quite distinctive’, giving a strong sense of her as a full person. This comes across in the photos, most of which focus on Kathleen’s daily routine and her relationships with neighbours and family, capturing them in intimate detail.

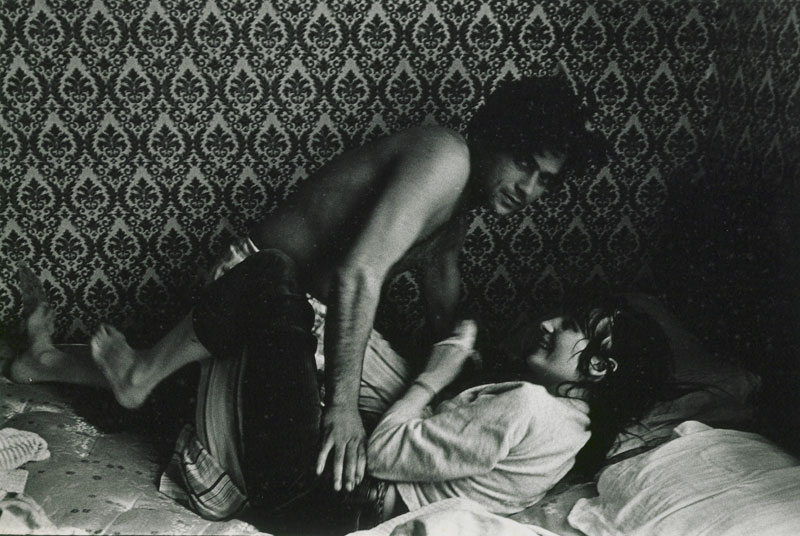

Kathleen and Salim at home (c. 1968), Janet Mendelsohn. Courtesy Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham

Reflecting on this Hilton says ‘there’s a certain simplicity about Janet and her work…I doubt that a British photographer, even a working class one, could have taken the pictures the way that she did. I certainly couldn’t have.’ His suggestion is that Mendelsohn’s position as a privileged outsider in Balsall Heath lent her and her project something of a sense of grace – a detachment from the uglier side of life there, that could be construed as naive.

This isn’t to say that Mendelsohn’s position in Balsall Heath was that of a spectator – a late ‘60s hybrid of Baudelaire’s flaneur and his female counterweight, the missionary women who dispensed housekeeping tips and bibles in the slums. That would be deeply unfair both to her and her project, which while neither condemning nor condoning, has a radical sympathy for the marginalised. Likewise, while her pictures are aesthetically impressive, there’s nothing staged about them. They’re honest in their simplicity: nothing is being sexed up in her depiction of sex workers and there’s little danger that the viewer will be drawn into complicity and the aestheticisation of poverty.

Untitled (c. 1968), Janet Mendelsohn. Courtesy Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham

Hilton hopes that visitors to the exhibition will be confronted with ‘the fluidity of social relations’ and come away appreciating that while people make choices ‘they’re often choices that they are forced into’. The pictures will be juxtaposed with snatches of tabloid reportage, and interviews that Mendelsohn conducted with people in Birmingham about their views on prostitution. These highlight dismissive and unpleasant attitudes of the ‘if it was my daughter I’d rather she was dead’ variety, but also the complex situations that led subjects into sex work.

At the end of our discussion, Hilton picks out one image in particular. It shows Kathleen lying on a bed smiling up at ‘Salim’, her boyfriend, the father of her children and her pimp. While Kathleen is grinning, Salim’s face is half turned to the camera: he looks dark, brooding and withdrawn. Hilton says ‘I find this image very problematic…They have a relationship, but that man’s a pimp, he’s living off her. I want people to see this, know that and know what it means.’

Kathleen and Salim at home (c. 1968), Janet Mendelsohn. Courtesy Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham

‘Janet Mendelsohn: Varna Road’ is at Ikon gallery, Birmingham, from 27 January–3 April.

*Mendelsohn changed the names of every subject in her study.