The first decades of the 21st century have been marked by epidemics: SARS in 2002–03, swine flu in 2009, Ebola in West Africa in 2014–16, Zika in 2015–16, and now Covid-19. Central to the general public’s experience of these events has been the use of photography. In recent weeks, we have seen this medium capture the impact of the new coronavirus across the globe – from the ways in which different countries are trying to contain it to the impact both of such measures and of the disease itself upon individuals and communities. Images of beleaguered hospitals, animals suspected as the potential origins of the pandemic, empty cities under lockdown, people swarming supermarkets for toilet paper, or expressing solidarity from their balconies have become visual staples of our increasingly online lives over the past couple of months. What is rarely considered is that the ways in which we visualise epidemics – and as a consequence, the way we experience them – were established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the course of an event that is all but forgotten in most parts of the world: the third plague pandemic.

Disinfecting Allahabad (1901/02). Courtesy Cambridge South Asia Archive (Fullerton Collection)

The third global wave of bubonic plague spread from south-west China, where it had been circulating since at least the mid 1800s, to Hong Kong in 1894 and from there, through maritime trade, to every inhabited continent, killing in its course more than 12 million people. The impact of the pandemic was enormous; it reshaped colonial governance across British, Dutch and French territories in Asia and Africa, as well as international trade, migration laws, and medical science. In some cases – like San Francisco, where large sections of Chinatown where demolished – it transformed the very fabric of cities.

Though photography had existed for more than half a century before the Hong Kong outbreak of 1894, newspapers had only recently acquired the technical capacity to publish photographs – and this was the first time an epidemic had been communicated to the public in this way. There was systematic, even obsessive coverage across the globe, as photographs taken by public health bureaus, doctors, journalists, colonial officers, missionaries, and ordinary members of the public found their way to the front pages. The result was a new genre: epidemic photography.

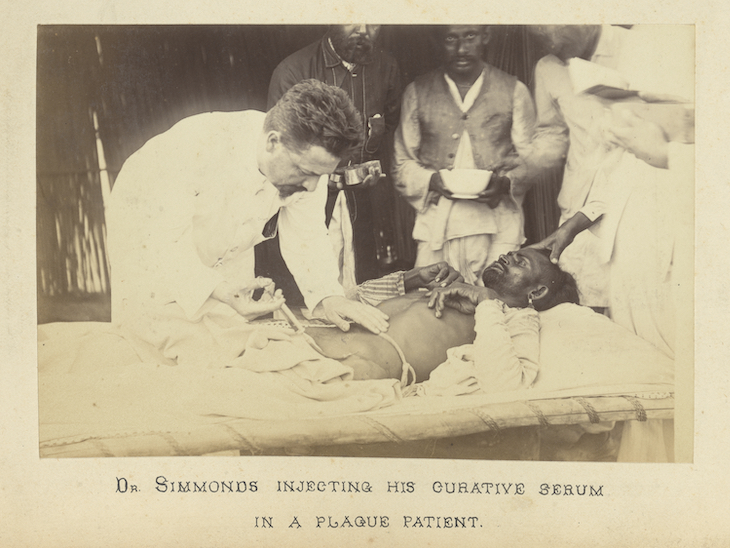

Paul-Louis Simond injecting his curative serum in a plague patient (1897). Wellcome Collection, London (CC BY 4.0)

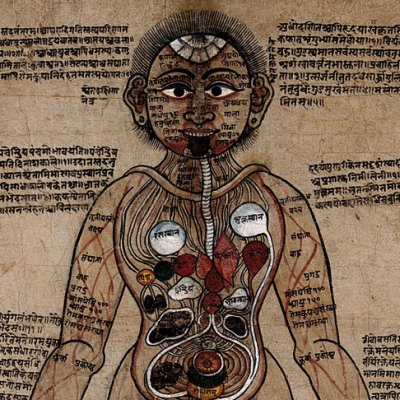

Medical photographs had already depicted symptoms, patients, and methods of cure. But now photographers began to focus on the causes of the disease, and measures for its control and containment. The plague bacterium had been identified in 1894 by Alexandre Yersin of the Institut Pasteur, but the transmission pathway remained uncertain, with theories involving the rat and its flea only gradually gaining acceptance. Photography was employed in the identification of the origins, vectors, and natural reservoirs of plague and its transmission pathways. These involved not only animals, such as rats or marmots, but also built structures and forms of habitation, as well as social behaviours and customs such as burial rites, believed at the time to be conduits of infection. Photographs in the press also depicted the means of containing and controlling plague: fumigation, disinfection, and vaccination featured centrally, but so did more radical and controversial approaches such as demolition, and even torching down sections of infected cities, as in the case of Honolulu. It’s important to note that since these photographs were taken within an imperial context, they reflect colonial ideologies and power structures at the time – for instance, in a photograph from the Karachi Plague Committee Album (1897), an Indian man is publicly subjected to a bath with disinfectants by British soldiers while an officer overlooks the operation, cane in hand.

In the disinfecting tub (1897), unknown artist. Wellcome Collection, London (CC BY 4.0)

Many of the visual tropes developed in the course of covering the third plague pandemic have stayed with us: the spectacle of epidemic burials, which we witnessed a few years ago during the Ebola epidemic, or the massive fumigation operations in China during the Covid-19 lockdowns in Wuhan and elsewhere. But there is also the focus on isolation, quarantine and sanitary cordons as essential methods of epidemic control. In a photograph from the album Views of Harbin (Fuchiatien) taken by Wu Liande during the plague outbreak of December 1910–March 1911, we see one of the harshest versions of quarantine in modern history: contacts of plague patients, held in immobilised train wagons in the Manchuria steppes, with temperatures below -20°C .

A women’s quarantine wagon (1910–11), Wu Liande. Courtesy of Needham Research Institute

The turn of the 19th century was the first time that photography was used to depict an infectious disease outbreak. But it was also the first time that such an outbreak was understood, both by scientists and the general public, to constitute a pandemic. Local outbreaks, no matter how small, captured by the photographic lens were no longer simply outbreaks in Porto, Los Angeles, Alexandria, Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Sydney or Mumbai – they were part of an event that was seen to threaten the fabric of the modern world. In fact, it can be argued that the wide coverage of this global outbreak, and the worldwide distribution in the press of photographs from even the smallest outbreak, played a major part in transforming the idea of the ‘pandemic’ from an arcane word in medical dictionaries to a word used and a condition experienced in everyday life. This field of vision and experience of the world is played out today before our eyes once again.

Research leading to this article was funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme/ERC grant agreement no 336564.

Christos Lynteris is senior lecturer in social anthropology at the University of St Andrews.