When he was in his mid-forties, Pierre Bonnard bought a Renault 11CV, had it painted pale yellow, and motored around France. A successful artist living in Paris, he explored the landscapes of Normandy and, driving south, the coast from Saint-Tropez to the Cap d’Antibes. Though he had visited the south of France before, staying with his mother at Le Grand-Lemps in the Dauphiné, this journey to the Mediterranean, with its terracotta villages and dramatic light, stimulated a change in his work. Back in the north, he bought a house in Vernonnet, a Normandy village not far from Paris, and began to paint with new energy, enriching his colours and recreating bright landscapes from memory. He would regularly drive to the coast, where he relocated in 1927, and his work absorbed the colours of his new surroundings. ‘Certainly colour had carried me away,’ he later reflected. ‘I sacrificed form to it almost unconsciously.’

The Bath (1925), Pierre Bonnard. Tate, London

At Tate Modern, these luminous paintings comprise the first major showing of Bonnard’s work in Britain for 20 years. Blue foliage and tropical skies fill enormous canvases, with views of bronze rooftops and greenish water. It’s a delight to discover Bonnard worked on such a large scale. The exhibition proposes that his feverish pastoralism was a late phase of creativity (in much the same way as Matisse has been given a final chapter), yet it also counters the critical dismissal of Bonnard as simply a ‘painter of happiness’. The curators draw on events in his life – the illness of his wife, Marthe de Méligny, the suicide of his lover, and the outbreak of the First World War – to reveal the turbulence beneath the colour. A paradisal garden painted in 1917 is, in fact, within earshot of the guns on the Front, while his late concentration on landscapes reflects his isolation, and the daily walks around the house in which Marthe confined herself.

Dining Room in the Country (1913), Pierre Bonnard. Minneapolis Institute of Art

The house at Vernonnet had a wild garden and views of the Seine. Unlike his friend Monet, who was painting a few miles away at Giverny, Bonnard wasn’t in the habit of painting en plein air. Instead, he would visit a scene several times and then work to capture it from memory, or he would paint the outside from within doors, as in Dining Room in the Country (1913), in which the crisp air is ushered into the room’s glowing interior through the open door. A female figure leans on the windowsill looking in, her red blouse extending the colour of the room into the garden, which falls away in mottled pastels. On close inspection the painting’s horizontal lines are uncertain. Windows and door frames are painted in wavering brushstrokes, a mark of Bonnard’s indecision as a painter, but also his attention to porousness, to the movement between interior and exterior environments.

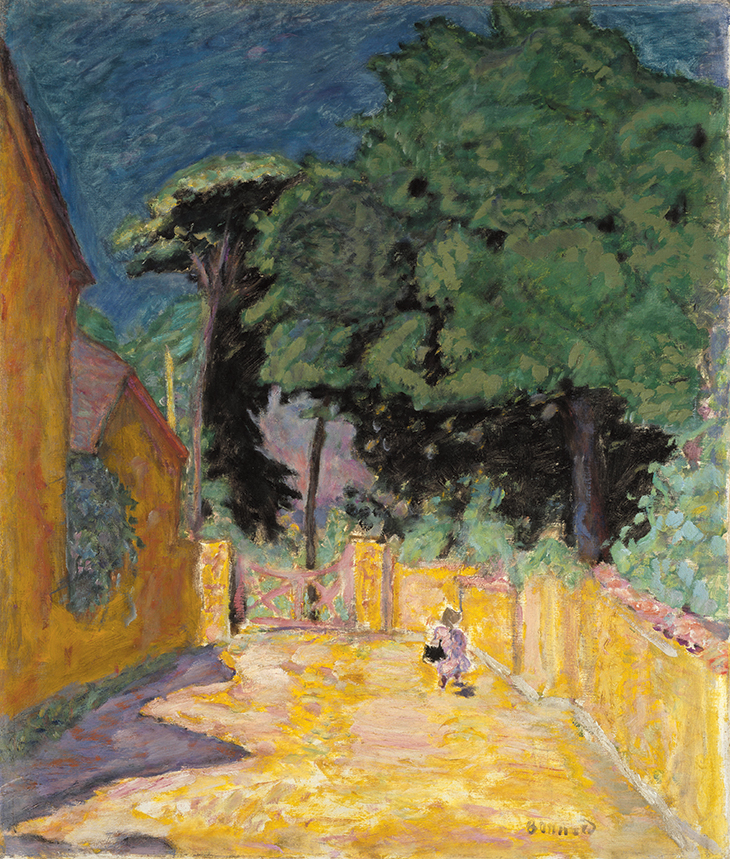

There are several of these monumental works in the exhibition, the most exuberant of which is Summer (1917), in which towering blue trees all but obscure the figures lolling beneath, their pointed leaves stabbing the orange lawn. Bonnard’s efforts at light and shade are not entirely successful and in the neon soup there are odd details, too, such as a small dog, motionless and dabbed in brown paint. It’s a lurid Eden, more bizarre than beautiful. Yet these larger works are complemented by smaller paintings in which a shorthand for his colours begins to emerge: the blue/green of the foliage of Summer and Lane at Vernonnet (1912–14) is the same used for the choppy waves in The Misty Bay (1914) and, in the final room, Bathers at the End of the Day (c. 1945). In the 100 works brought together for the show, forests and seas are evoked in similar murky tones, practising the same effects of light and dark. In this new phase, Bonnard moved between Normandy and Cannes, each outdoor world feeding into the other.

Lane at Vernonnet (1912–14), Pierre Bonnard. National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

Marthe’s presence is felt throughout. She appears in the margins of domestic interiors, her reflection caught in a pane of glass, or dwarfed by plantlife as she works in the garden. She’s slight, feline, a little evasive, and used to being observed. Bonnard’s paintings capture the tenor of their domestic life – the couple lived together for 30 years before marrying in 1925, provoking Bonnard’s lover, Renée Monchaty, to kill herself – and the central role played by Marthe’s illness. The frequency with which he painted her bathing – stooping over a tub as in Nude Crouching in the Tub (1918), or with her body submerged underwater – is now considered evidence for hydrotherapy, a daily water ritual to ease her various physical complaints. The Bath (1925) was the first of four paintings Bonnard would complete over 20 years that show Marthe’s elongated body. She’s neither erotic nor obviously ill; instead, the viewer is drawn to the ordinariness of her form, her shapeless purplish legs, her small belly and breasts, her preoccupied expression. It’s an intimate moment, yet the painting’s composition is stark, the white bath beneath a row of tiles reducing the painting to bands of colour, of which Marthe’s body is one. Elsewhere, Bonnard defamiliarises Marthe’s bathroom – the ‘one luxury’ she requested when the couple moved to Le Cannet in the south of France – so that it becomes a neutral and medicinal space. In In the Bathroom (c. 1940), Marthe’s toiletries become abstracted lozenges of colour, a collection of Bonnard’s scumbling paint marks.

Nude Crouching in the Tub (1918), Pierre Bonnard. Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

Marthe is liveliest in motion. A series of small photographs, taken in 1900, show her naked in the garden at Montval, standing beside a chair, crouching in long grass, stooping beneath trees. Bonnard’s interest in photography informed his study of the female form; studying Marthe through a lens, he was able to replicate the casualness of her movements. The paintings in which she is dressing, such as Nude Against the Light (c. 1908), show the physical assertiveness of her younger body, the purposefulness and pleasure of her daily routine. Behind her, the room’s surfaces fizz into ribbons of blue, green and yellow. Certainly, Bonnard let himself be carried away by colour, and sacrificed form to it, too. But he also understood it as a sensory experience, and a way of apprehending the world.

‘Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory’ is at Tate Modern, London, until 6 May.

From the March 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.