For some 30 minutes before the sun makes its morning appearance or gives way to the long polar night, Norway’s skies are suffused with cobalt blue. Since 2023, those gazing up to take in the phenomenon of blå timen – Norwegian for ‘blue hour’ – in the west coast city of Trondheim may have found their sightline interrupted by a rainbow. This is no accident of light, but the work of Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone, whose multicoloured sculpture our magic hour (2003) arches over one of the eaves of Trondheim’s newest art museum, PoMo.

The museum is a cheerful sight on the freezing February day I visit, with its pale green cladding, fuchsia front door and art nouveau architecture. Designed in 1911, the building was formerly the city post office – the museum’s full title, Posten Moderne, nods to this history. Since opening in February 2025, PoMo has presented its growing permanent collection of contemporary art, put on an exhibition of Picasso’s paintings and ceramics and is currently presenting a major show on Louise Bourgeois. When the museum first opened the doors last year, its director, Marit Album Kvernmo, was a little nervous: ‘We asked ourselves, will anyone visit?’ she tells me. These jitters, it turned out, were unnecessary: the opening was packed and visitor numbers have been steady since.

PoMo is funded by Trondheim locals Monica and Ole Robert Reitan of the retail and real-estate conglomerate Reitan AS. Its purpose, Kvernmo says, is to ‘make the entire region love art more’. The permanent collection comprises 40 works by artists including Sol LeWitt and Robert Irwin but, surprisingly, just one Norwegian artist: Sandra Mujinga, who works in sculpture and photography. This, Kvernmo explains, is part of PoMo’s policy of bringing international art ‘seldom shown in Norway’ to Trondheim. The museum is also looking to address the gender imbalance of works in the country’s collections by allocating 60 per cent of its acquisitions budget to women artists. The programming, which includes displays of work from the Reitans’ private collection – Munch, naturally, is a highlight – declares the museum’s ambitions to prospective visitors, Kvernmo explains. ‘They might not have heard of Simone Leigh or Anne Imhoff […] but they’ve heard of Picasso, they’ve heard of Bourgeois, they’ve heard of Munch. We invite them in for those big artists, [but] they leave with the others.’

PoMo’s connection with Bourgeois tracks back decades, before the museum was even thought of. A sculpture by the French-American artist was the first work the Reitans ever acquired; ‘Echo of the Morning’ is an apt choice for the show. The exhibition takes place across the museum, with sculptures dotted across the ground floor, but at the centre of its main space on the top floor are gouaches that Bourgeois made in the last four years of her life. Assembled by curator Philip Larratt-Smith, who worked with the artist on her literary archive in the final decade of her life, it is a packed and striking display, quelling any concern that the museum might have oversold what it describes as a blockbuster show.

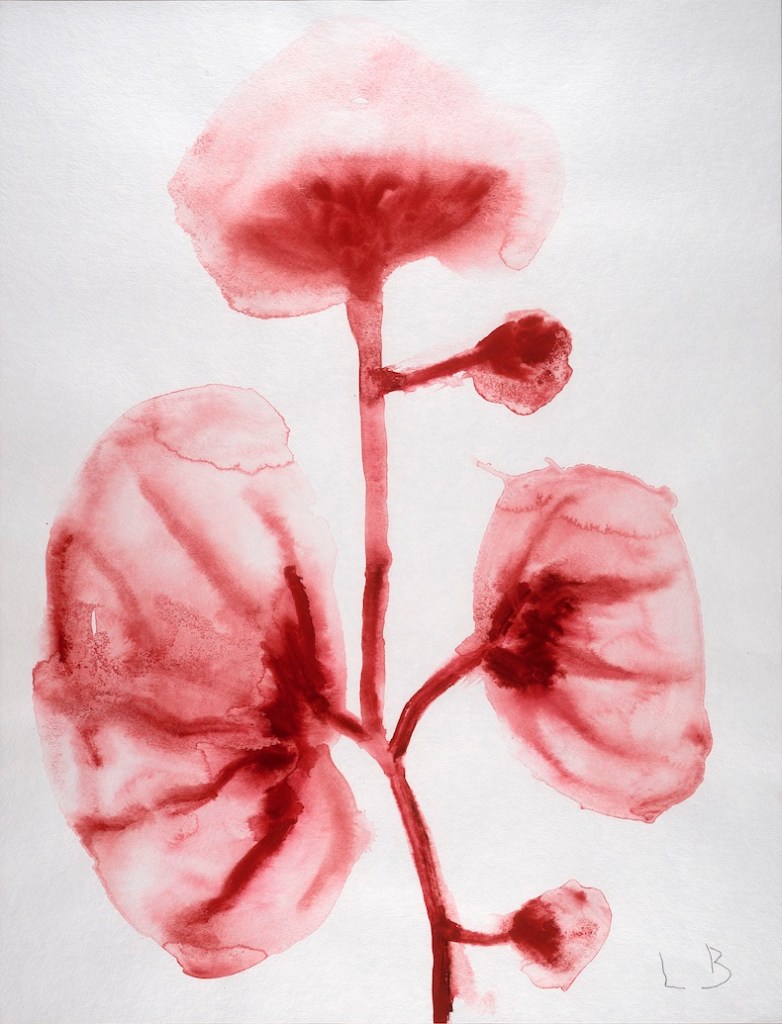

The gouaches are red and fervent and show an artist mining the themes that informed her oeuvre right to the end: birth, sex, motherhood, family and an unrelenting interest in her own psychology. Many were painted in single sittings, wet-on-wet, and in them, says Larratt-Smith, is a ‘dispensing of anything that’s not relevant or necessary’. Series such as The Family (2007) are pared back, presenting two simple forms, one with an engorged belly and breasts. At the edge of each mark, the paint bleeds, distorting the mother’s form, while words scrawled in pencil across the surface evoke the artist’s complex relationship with the maternal role, ‘devotion’ and ‘eternity’ paired with ‘sacrifice’ and ‘pity’.

Symbols of the mother-child relationship crop up across the exhibition: in The Feeding (2007), a child breastfeeding is almost imperceptible amid a wash of red. Les Fleurs (2009), a suite of 12 gouaches, shows five blossoms spurting from a central stem – Bourgeois’s immediate family, in childhood as in motherhood, comprised five members. Swollen and brownish-red, they also suggest lungs, or embryos. Bourgeois lost her mother as a young woman: at the end of her life, Larratt-Smith says, she saw herself as a yearning infant again. Though understanding this background adds a layer to her work, it’s not essential. As Larratt-Smith says, ‘You can look at the work without knowing anything about her and still be profoundly affected.’

This rings true not just in the gouaches but also in the smattering of textile and sculptural pieces also present. Self Portrait (2009) is a bedsheet with a 24-hour clock stitched on to it, each hour representing a stage of Bourgeois’s life, from girlhood and marriage to motherhood and art-making. Spider Couple (2003) shows two of Bourgeois’s signature bronze arachnids twisting their limbs together, the smaller cowering beneath the other like a child wary of strangers. One of the most intriguing works here is PoMo’s very own Bourgeois, Arch of Hysteria (2004). A small, knitted sculpture, it fuses together the torso of a man and a woman and dangles like a trapeze artist from the ceiling. Bourgeois created many versions of this arched figure, incorporating male characteristics to counter the notion of ‘hysteria’ as a female-only affliction.

Back on the ground floor, it’s clear why the PoMo team sees the museum as the jewel of the city’s new cultural quarter: this airy venue, with its ambitious programming and ever-growing collection, has grand plans. It’s also rooted in a city with a long cultural history: ten minutes’ walk from the museum (everything here is ‘just ten minutes away’, the locals tell me) stands the city’s remarkable gothic cathedral, Nidarosdomen. Nearby is the Trondheim Kunstmuseum, currently showing works by the Sámi artist Outi Pieski; take a brief stroll in the cold and you’ll arrive at the Kunsthalle Trondheim, another new space for contemporary art. In a way, PoMo’s role in the city rhymes with its own objective: people may come to Trondheim for PoMo’s shows, but there’s plenty more to stick around for.

‘Louise Bourgeois: Echo of the Morning’ is at PoMo, Trondheim until 31 May.