From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

This month marks 300 years since Robert Walpole (1676–1745) became Britain’s first ‘Prime Minister’. The title was not a formal one; it still exists only through political convention. However, with the positions he attained in April 1721 – First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer – Walpole was able to amass power to a degree previously unprecedented, as the right-hand man of Britain’s newly imported Hanoverian monarchs. The period of his ascendency, popularly dubbed the ‘Robinocracy’, lasted for nearly 21 years and, for sheer duration, remains unbeaten. Under Walpole, the Whig government’s priorities were an obsessive and often unpopular avoidance of foreign wars, dramatic reductions in the land tax and, above all, the consolidation of Hanoverian rule under George I and his son George II.

In a print by one of the period’s most prolific engravers, George Bickham the Younger, the premier’s face looms large. A great yawn exposes rows of carnivorous teeth beneath a pointed, vulpine nose. Though the eyes are heavy, they are still watching. It seems to be a portrait of indolently sprawling power, total and uncontested. ‘What Mortal’, asks the caption, quoting Alexander Pope’s satirical Dunciad, ‘can resist the Yawn of Gods?’ In fact, Bickham’s portrait was retrospective – The late P-m-r M-n-r was published a year after its subject’s political downfall in 1742 (and four years after Britain’s entry into the ‘War of Jenkins’s Ear’, which Walpole had opposed), hence the gloating inscription below the main image, ‘Lo! What are all your schemes come to?’

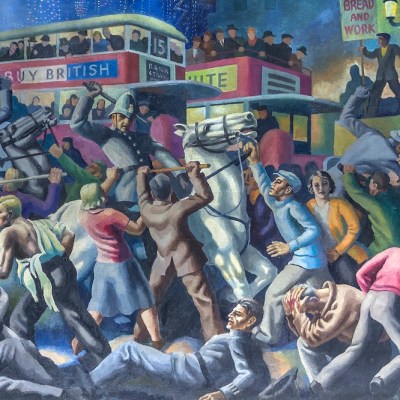

The ‘Robinocracy’ witnessed a new flowering of political print satire created by the network of artists, engravers, publishers, print sellers and consumers then developing around the coffee shops and commercial centres of the City of London. Walpole was widely believed to maintain his power – and the vast personal wealth that allowed him to amass a superb collection of Old Masters at his family estate, Houghton Hall – through bribery and corruption. ‘Robin’ also pushed for consumer taxes on tea, coffee, chocolate, alcohol and tobacco, guaranteeing him enmity from the professional and mercantile classes that increasingly formed the primary market for prints. In the teeth of sporadic attempts at censorship, many artists and engravers gleefully exploited the scandals and factionalism surrounding ‘Robin of Bagshot, alias Bob Booty’ – the pseudonym popularised in The Beggar’s Opera, John Gay’s wildly successful satire on Walpole, court manners and Italian opera, which premiered in 1728.

‘According to our constitution, we can have no sole and prime minister,’ declared Samuel Sandys in 1741, complaining that Walpole ‘ha[d] monopolized all the favours of the crown, and […] made a blind submission to his direction […] the only ground to hope for any honours or preferments’. Since his power inhered not in his position, but in his person, and in his dense networks of influence, printmakers found rich material in Walpole’s corpulent body, often represented (as in The Late P-m-r M-n-r) as outsized and grotesque. In the anonymous Idol-worship or The Way to Preferment, published in 1740, Walpole’s bare buttocks sprawl over St James’s Palace, forming the first arch in a great enfilade into the inner sanctum. A tiny sycophant clambers up the entrance post to kiss his ‘idol’, while another runs a hoop between his legs. A similar print by Bickham presents him as The English Colossus, his pockets stuffed with the contents of his famous ‘Sinking Fund’, officially intended to defray the national debt. Walpole straddles a harbour-mouth supported by twin wool-packs, dwarfing a sailing ship with his bulging calves. The caption quotes Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar who stands ‘bestride the world like a Colossus’, but far from being a warlike hero, this Colossus is a dead weight. At his heels, Lilliputian marines beg ‘Let us fight on’, but he holds a sword marked ‘for peace’.

Others found material in historical precedent. On the death of George I in 1727, Walpole was briefly ousted by the Prince of Wales, now George II, who had resolved to rid himself of the ministers of his hated father. Walpole managed to claw his way back, partly through his close friendship with Queen Caroline. A print from this period by William Hogarth was widely believed to show the disgruntled premier as Cardinal Wolsey glowering from the shadows as his sovereign leads the newly ascendent Anne Boleyn to the throne. Hogarth’s idea probably came from an essay in The Craftsman, an anti-Walpole periodical that, from 1726, gave regular vent to the satirical mockery of opposition Tories, led by Henry St John, Viscount Bolingbroke, but also associated with writers such as Gay, Pope, Fielding and Swift. A copy protrudes from the pocket of a man drunkenly setting his own ruff alight in another of Hogarth’s prints of the same period, A Midnight Modern Conversation (1733), where its juxtaposition with the pro-Walpole London Journal offers some context for the riotous devastation that has ensued.

The Craftsman’s declared purpose was to expose how ‘the mystery of State-Craft’ abounded with so many ‘Frauds, Prostitutions, and Enormities in all Shapes and under all Disguises’ as to create ‘an inexhaustible Fund […] for Satire’. An anonymous mezzotint of 1736 unveils one ‘Disguise’, revealing Walpole’s face as a mask that he removes to uncover a terrifying visage, contorted into a sneer. ‘You are all Bit, Ha ha ha!’ cackles the caption, giving the lie to the adjacent quotation from Ecclesiastes, that ‘A Man may be known by his look’. Indeed, for many of his contemporaries, Walpole came to encapsulate the hypocrite politician, and it is telling that several of the satires first designed for him were subsequently re-used or adapted for others. The English Colossus was reissued with the face of Lord Bute and, in 1797, James Gillray used the same idea against William Pitt the Younger – by which point the position of ‘Prime Minister’ had begun to solidify, and British print satire had entered its golden age.

From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.