Introducing Rakewell, Apollo’s wandering eye on the art world. Look out for regular posts taking a rakish perspective on art and museum stories.

While Rakewell was not expecting Prince Harry to have much to say about the Royal Collection, your reluctant royal correspondent has been reading Spare to see if there are any stray details about what it was like to grow up with one of the most important art collections in the world. The pickings are understandably slim, but it’s hard not to be tickled by Harry’s description of being told to bow to a statue of Queen Victoria on the second floor of Balmoral. More treacly is the account of staying at Tyler Perry’s house in California and infant Archie being drawn to a painting of ‘a scene from ancient Rome’. On closer inspection it turns out to be:

Goddess of the hunt. Diana.

When we told Tyler, he said he hadn’t known. He’d forgotten the painting was even there.

He said: Gives me the chills.

Us too.

But, as Rakewell always says, why read meaning into coincidence when there is some actual close-looking to be done? Now that even the most committed anti-monarchist can tell you what an heir and spare is, Rakewell can’t help feeling that the family art collection could have helped Harry have more realistic expectations of what lay ahead; acting as a prompt, perhaps, to head for the hills even earlier. If there’s one thing the Royal Collection is strong in, it’s portraits of royal children. Several British monarchs have also shown an interest in acquiring the likenesses of their less fortunate European counterparts. (Fraternal feeling or schadenfreude?) And if there’s one thing that unites all these portraits, it’s the compositional focus on the heir and the relegation of their siblings to the shadows, sometimes literally, as even a quick look at some masterpieces of the genre show:

The Five Eldest Children of Charles I (1637) by Van Dyck

It’s clear who is top dog here.

The Five Eldest Children of Charles I (1637), Anthony van Dyck. Royal Collection Trust. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/© His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Françoise de Souvré, marquise de Lansac, et les enfants de France (c. 1643), attrib. Pierre Mignard

The royal governess may seem like the main attraction, but her real function is to point at Louis XIV and the duc d’Orléans – and of her young charges, it’s only the future Sun King who gets to make eye contact with his future subjects.

The young Louis XIV with his brother Philippe and his governess Françoise de Souvré, marquise de Lansac (c. 1643), attrib. Pierre Mignard. Wikimedia Commons

The Royal Family in 1846 (1846), Franz Winterhalter

Five of Queen Victoria’s and Prince Albert’s children pose with their parents, but only the Prince of Wales is held by the monarch – and his exchange of looks with his father suggests something of a shared manly understanding. (Prince Alfred is a baby and can only be cooed over by his sisters.)

The Royal Family in 1846 The Royal Family in 1846 (1846), Franz Xaver Winterhalter. Royal Collection Trust. Photo: Royal Collection Trust/ © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

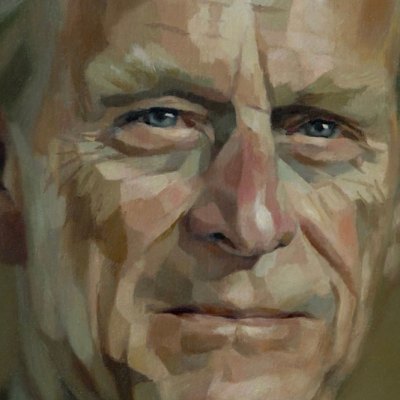

William, Prince of Wales; Harry, Duke of Sussex (2009), Nicola Jane Phillips

The first official portrait of the brothers shows them both in the uniform of the Household Cavalry. They may look equal, sharing an amused look, but the figure who’s standing over a seated figure always has the upper hand, as it were.

William, Prince of Wales; Harry, Duke of Sussex (detail; c. 2009), Nicola Jane Philipps. National Portrait Gallery. Photo: Nathan King/Alamy Stock Photo

Got a story for Rakewell? Get in touch at rakewell@apollomag.com or via @Rakewelltweets.