What is it about statues? Most obviously, sculpture – not least the statue – has been understood as a predominantly public art and those images that have been the focus for recent protests have been in public spaces. As Byron remarked (albeit of the portrait bust rather than the statue), a portrait sculpture ‘smacks something of a hankering for public fame rather than private remembrance’ and, unlike the painted portrait, ‘looks like putting up pretensions to permanency’. The avowed purpose of portrait sculpture has traditionally been, in the words of the 18th-century sculptor Etienne-Maurice Falconet, ‘to perpetuate the memory of illustrious men and to give us models of virtue’. But, as many recognised at the time, those commemorated in this way were often far from being ‘models of virtue’. The claim that a statue represented a subject worthy of respect and admiration meant that it could easily be mocked or attacked, and it is hardly surprising that within the history of iconoclasm – a significant part of the history of responses to images – statues and their downfall figure prominently. The suggestion of permanency also went with the materials employed, above all marble or bronze, and this claim to longevity invited challenge or rebuttal, as poets from Horace to Pope and Shelley have recognised.

As well as being often set up in public spaces, statues are not contained within frames like painted portraits but share the same space as the spectator. Though distanced by being set on plinths, so emphasising their authority, the setting of these images allowed their viewing to be to some degree unmediated. It is this apparent directness that can affront or startle, hence the trope of statues being perceived as being alive. But exterior, urban settings were not the only locations for sculptural commemoration. Henry Cheere’s statue of the plantation owner, Christopher Codrington, for example, was set up in the library that bears his name at All Souls College in Oxford. (In 2018 All Souls installed a plaque that explicitly acknowledges the sources of Codrington’s wealth in the entrance of the library.) Nor did statues necessarily stand alone. The image of William Beckford, another figure whose riches came from sugar plantations in Jamaica, forms part of a large monument in the Guildhall in London. Some of the most imposing monuments set up in the 18th century are to be found in churches, not least Westminster Abbey. Many of those commemorated, as contemporary satirists endlessly pointed out, were far from exemplary or even distinguished, their monuments and the inscriptions upon them amounting to what Pope described as ‘Sepulchral lies’.

Many of those whose public statues are currently under scrutiny were also commemorated in such spaces. The contemporary monument to Colston was not the bronze recently toppled from its plinth – that was put up as recently as 1895 – but Michael Rysbrack’s magnificent effigy of 1729 in the church of All Saints in Bristol, while, only feet away from Thomas Guy’s bronze statue in the courtyard at Guy’s Hospital, is a fine monument to him inside the chapel. Among the most inventive works by John Bacon, this shows Guy, almost a self-standing statue, placed against a relief of the hospital, and reaching down to a single figure representing the sick and poor. Statues such as Peter Scheemakers’ figure of Guy (in the hospital’s courtyard) or Sir Richard Westmacott’s Robert Milligan, which are seen as individual public images, form part of a broader continuum of sculptural portraiture, though it is understandable that it is those in urban situations that have attracted most attention recently.

Monument to Thomas Guy (1779), John Bacon, in the chapel at Guy’s Hospital, London. Photo: Apollo

All these images – though some more tellingly than others – belong to a larger history of British art, along with the painted portraits representing many of the same subjects. To point out the aesthetic quality of some of these sculptures is not to suggest that statues should be valued only as autonomous works of art without regard for the connotations they originally had or, equally importantly, those which they have acquired since their erection. Many public statues – Sir Francis Chantrey’s bronze of William Pitt the Younger at the junction of George Street and Dundas Street in Edinburgh, for instance – play a dynamic role within urban landscapes, as well as being distinguished works of sculpture in their own right. Such settings are important for the staging of sculpture and condition its viewing. Others, especially some executed in the 18th century by sculptors such as Rysbrack or Louis François Roubiliac, deserve to take their place within the canon of British art, despite the fact that neither name is as familiar Hogarth or Reynolds. While contemporaries in the mid 18th century may have mocked the grandiosity of some monuments and the insignificance of those they commemorated, the increasing recognition of the aesthetic qualities of many of these works is clear. By the late 18th century guidebooks to Westminster Abbey were putting as much emphasis on the ‘invention’ apparent in the composition and execution of recently erected monuments as on the achievements of those commemorated and described in the epitaphs inscribed on them. As Oliver Goldsmith’s fictional Chinese traveller comments in The Citizen of the World (1762), on ‘new monuments erected to the memory of several great men […] such monuments as these confer honour, not upon the great men, but upon little Roubillac [sic]’.

The cast of Michael Rysbrack’s statue of Hans Sloane (original 1737) in the Chelsea Physic Garden, London

Although the tradition of erecting family monuments in churches was of course a long-standing one, the erection of monuments to figures other than the monarch became far more frequent in the 18th century, so coinciding with the expansion of the slave trade and the growth in wealth derived from it. One emergent category of statue comprised statues to benefactors. Among them were Grinling Gibbon’s Robert Clayton (for St Thomas’ Hospital), Scheemakers’ Thomas Guy (for Guy’s Hospital), Rysbrack’s Dr John Radcliffe (in the Radcliffe Camera in Oxford) and Hans Sloane (formerly in the Chelsea Physick Garden, now in the British Museum), and Roubiliac’s Sir John Cass. Since all apart from Radcliffe had benefitted to varying degrees from the slave trade, each of these statues may retrospectively be seen as tainted. At the same time, they together show how what had been a limited genre was being reconfigured in new ways.

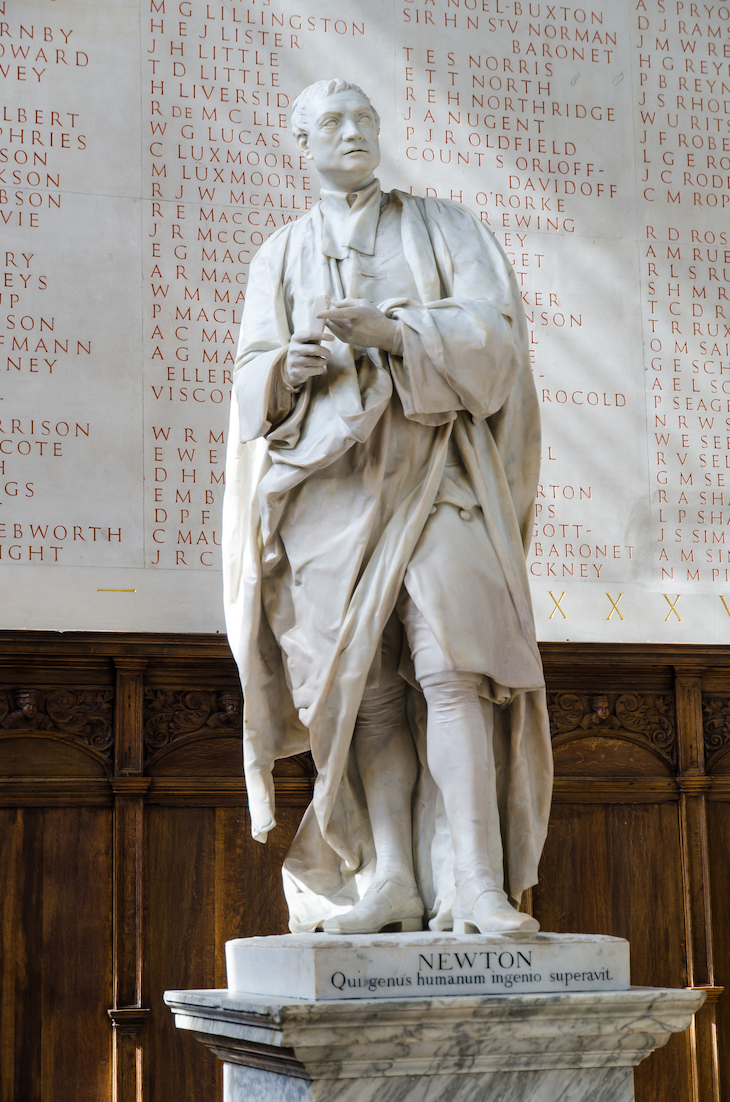

The animation of the statue – involving movement that engaged the viewer in unexpected ways – was indeed one of the striking and innovative features of sculptural portraiture at this time. Nowhere was this more evident than in statues to thinkers, writers and others who owed their fame to their creative achievements, so constituting a new type of subject. With figures such as Roubiliac’s Handel (made for Vauxhall Gardens and now in the V&A) or Rysbrack’s John Locke (on the library stairs at Christ Church, Oxford), sculptors raised their aesthetic game as well as the standing of the statue as a genre. This was recognised at the time by some acute observers. Commenting in 1755 on the recently erected statue by Roubiliac of Newton at Trinity College, Cambridge, John Nevile asserts that ‘I never saw so much life in any statue before,’ and, in a detailed account citing Hogarth’s recently published Analysis of Beauty (1753), praises it as ‘a masterpiece of the kind’ with an ‘an attitude [that] is the most easy and graceful you can imagine’. Increasingly, statues and other forms of sculpture were being viewed in aesthetic terms. While a great portrait by Hogarth, such as that of Captain Coram in the Foundling Museum, may be familiar to anyone interested in 18th-century British art, the same cannot be said be said of Roubiliac’s Newton, even though it is just as impressive and innovative an image. At their best, statues by Roubiliac and Rysbrack show a conventional and fairly static genre being newly animated and endowed with a drama to which spectators accustomed to the acting of David Garrick responded so readily. Likewise, their marble surfaces are worked with a new subtlety that invites close and sustained viewing. This reconfiguration of the statue’s familiar conventions in works such as Rysbrack’s Locke or Roubiliac’s Newton brought to British sculpture a new complexity and ambition.

Statue of Isaac Newton (1755), Louis François Roubiliac, at Trinity College, Cambridge.

As we talk about statues in terms of their subjects, and rightly question the implicit claims made by the genre to celebrate ‘models of virtue’, should we not look at some of them more attentively as sculptures? It is ironic that some of the most remarkable examples have been almost entirely ignored, not only by those who have walked past them daily, but also by the majority of art historians. Perhaps readers returning to the British Library might even give more than a passing glance to Roubiliac’s statue of Shakespeare (albeit now sadly deprived of its original plinth), as they ascend the steps to the reading rooms.

Malcolm Baker is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Art History at the University of California. He is the author of The Marble Index: Roubiliac and Sculptural Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Britain (2015), published by Yale University Press.