Introducing Rakewell, Apollo’s wandering eye on the art world. Look out for regular posts taking a rakish perspective on art and museum stories

Amateur carvers and costume-makers rejoice: the spookiest time of year has arrived. While the origins of the practice are shrouded in myth, it has been customary since at least the 19th century (particularly in Ireland and the USA) to mark the night of 31 October with the lighting of jack-o’lanterns – otherwise known as hollowed-out pumpkins (or once, apparently, turnips). This Halloween your correspondent is celebrating with a festive harvest of art featuring pumpkins – lit, carved, or otherwise.

Incised gourd vessel (2nd century BC–3rd century AD), Peru. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The tradition of decorating gourds is a long and varied one – the indigenous peoples of Peru in particular are known for their highly detailed mates burilados, such as this incised and hollowed-out example in the collection of the Met Museum in New York.

Still life with Fruit, Oysters and a Porcelain Bowl (1660–79), Abraham Mignon. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Native to the Americas, pumpkins were introduced into the diets of European settlers in the late 15th century. (They were originally, it is thought, mistaken for large melons – the word ‘pumpkin’ is related to the ancient Greek word pepon, meaning melon.) Thenceforth they began appearing in that suitably eerie genre of painting, the still life. The compact example in this picture is almost the same size as a nearby oyster shell.

‘Pumpkins used as dwellings to secure against wild beasts’, plate 7 from ‘The collection of most notable things seen by John Wilkins, erudite English bishop, on his famous trip from the Earth to the Moon’ (after 1783), Filippo Morghen. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Filippo Morghen was an engraver, publisher and print dealer working in 18th-century Italy. This etching is one of a series of fantastical scenes depicting the imagined lunar voyage of John Wilkins, a clergyman and philosopher – and brother-in-law to Oliver Cromwell – who in the 17th century wrote a number of scientific works proposing the existence of living beings (called ‘Selenites’) on the moon. In another of Morghen’s etchings, a pumpkin is fashioned by the Selenites as a fishing craft.

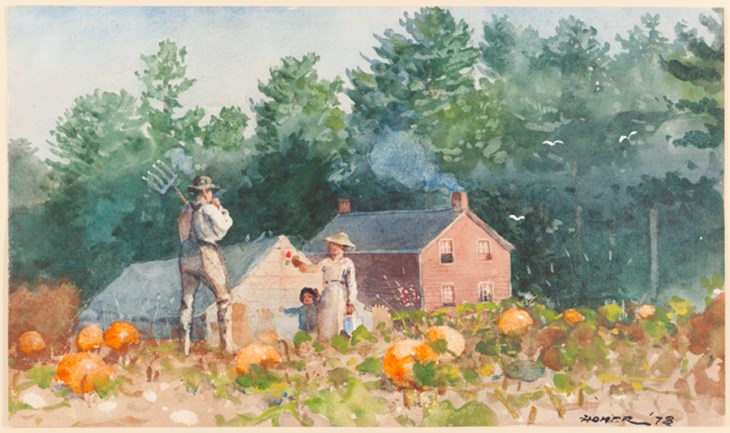

Pumpkin Patch (1878), Winslow Homer. Mead Art Museum, Amherst

Winslow Homer may be best known for the seascapes of his late career, but he seems to have also found plentiful inspiration in pumpkin patches. This is one of several watercolours and prints he made of pumpkin harvests and other rural scenes, an American twist on the landscapes of the influential Barbizon School painters in France.

Girl with lit pumpkin (c. 1955), Joe Clark. Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Although the customs of Halloween are believed to have Gaelic roots, today it is considered primarily an American festival. This photograph of a girl waiting with her pumpkin for guests to arrive at her family’s Halloween party is by the American photographer Joe Clark, who went by the nickname ‘the Hillbilly Snap Shooter’.

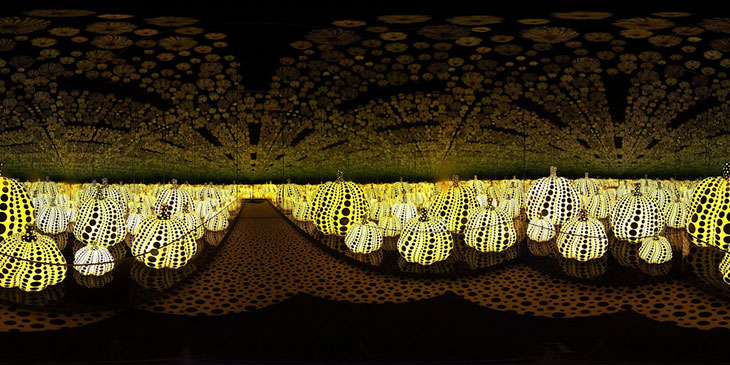

Panoramic installation view of All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins (2016), Yayoi Kusama, at the Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., 2017. Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images

The pumpkin – spotted, of course – is perhaps the most recognisable motif of Yayoi Kusama’s work; her passion for the plant inspired her most recent ‘Infinity Mirror’ room: All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins. ‘I love pumpkins,’ she has said, ‘because of their humorous form, warm feeling, and a human-like quality.’

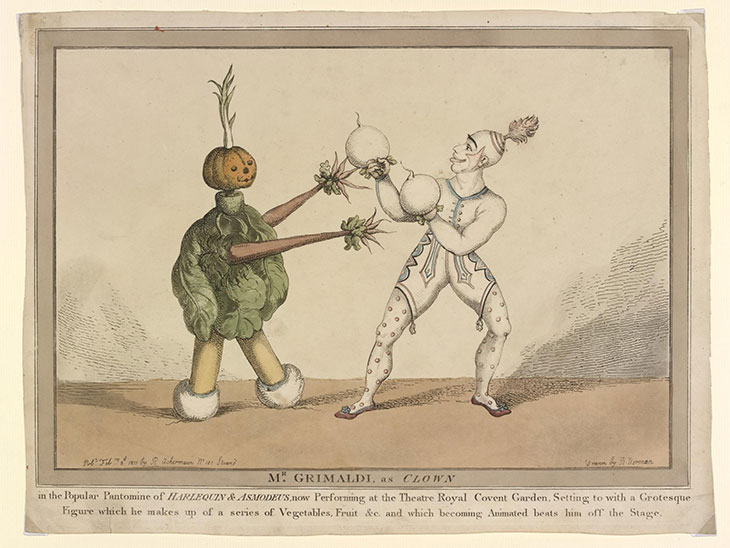

Mr. Grimaldi as Clown (1811), published by Rudolph Ackermann from a drawing by R. Norman © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Finally, if you’re seeking some costume inspiration this year: look no further than this engraving of the popular Regency-era clown Joseph Grimaldi in a boxing match against a man made of vegetables. In a tribute to Grimaldi upon his retirement in 1828, the writer Thomas Hood wrote a poem containing the lines: ‘For who like thee could ever stride! / Some dozen paces to the mile! / The motley, medley coach provide / Or like Joe Frankenstein compile / The vegetable man complete! – / A proper Covent Garden feat!’.

Got a story for Rakewell? Get in touch at rakewell@apollomag.com or via @Rakewelltweets.