It may be one of the first things that speakers of Arabic notice, but it is likely to be lost on the rest of us. The Institut du Monde Arabe’s new exhibition, ‘Habibi: Les Révolutions de l’Amour’, has an Easter egg in its Arabic title. Curators Élodie Bouffard, Khalid Abdel-Hadi and Nada Majdoub wanted to use gender-neutral, inclusive language in both the French and Arabic texts used throughout the show. In the show’s title, the masculine habibi (a term of endearment meaning ‘my love’ or ‘darling’) is combined with the feminine form habibti, courtesy of font design by graphic design agency Studio Akakir. It’s a detail that shows how the curators have tried to think of everything. And yet, their attempt to provide an exhaustive representation of queerness across the Arab and Persian world has in fact spread the subject matter thin.

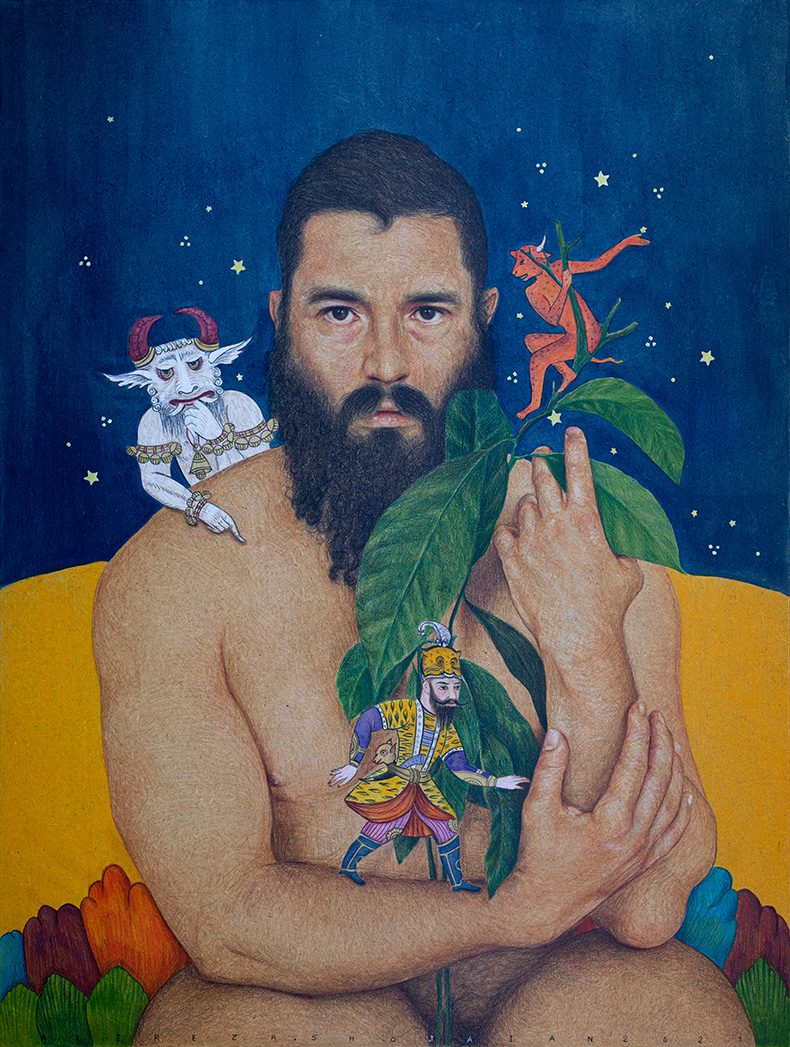

The show opens with works by the Iranian artist Alireza Shojaian, whose acrylic-and-pencil Sous le ciel de Shiraz, Arthur (2022) was chosen as the poster for the exhibition. Shojaian’s male nudes, sitting or reclining comfortably in intimate, domestic settings, look tenderly back at the viewer. His use of coloured pencils makes their skin and hair seem soft and lustrous, inviting touch. He puts the male body in positions of vulnerability or traditional femininity – gazing into a mirror, surrounded by flowers or in a private moment of heartbreak. Motifs from traditional Persian miniatures accompany his characters, like the small figure on horseback in Tristan, Jardin Persan – Toile (2020) representing Khosrow, the hero of a tragic love poem in Persian literature. Shojaian’s muscular men are recast as heroes or lovers – but unlike Khosrow, Tristan is denuded of his armour. These defenceless men are heroes of a new type of love story.

Sous le ciel de Shiraz, Arthur (2022), Alireza Shojaian. Courtesy the artist and Galerie La La Lande; © Alireza Shojaian

An installation by artist duo Jeanne et Moreau continues the theme of domestic space and the representation of intimacy. Visitors can scroll through their private photos on an iPhone placed next to a bed, in front of a screen adorned with a photo of one of the artists napping naked. The inclusion of personal photos (the two artists are a real-life couple) in their artwork evokes the fluid border between what we make public and what we keep private – an issue that takes on even more significance for queer people in much of the Arab world: how much of themselves to reveal?

Hands Routine by the Lebanese artist Omar Mismar tracks the dichotomy of private and public, in and out, in the form of a timeline. He charts when he held hands with his partner over the course of a day, minute by minute, recording what made them let go – an adjacent car higher than theirs, needing a hand free to tune the car radio, sipping a drink, a passer-by who may see them – drawing attention to the hyper-vigilance and self-censorship of gay men in societies where homophobia is prevalent.

But the exhibition isn’t about repression – or not only. There’s a lightness to the show, from the camp, tinselly costumes of Lebanese drag queens to the steady thump of Arabic disco-pop that ripples out from the ‘Ballroom’, and a circular video room where short films are interspersed with projections of queer, sequin-clad belly dancers sashaying across the wall. The visitor walks down a staircase in the second room of the exhibition as though descending into a basement club and the atmosphere changes: pink neon now demarcates different sections of the room and ultraviolet light makes the wall text glow.

The Girl (2021), RIDIKKULUZ. © RIDIKKULUZ

There is no timidity here; with assured strokes, illustrator Léa Djeziri draws the brazenness of feminist and queer activists in modern Tunisian society, while people look coolly and boldly at French photographer Camille Farrah Lenain’s camera lens. ‘It’s through other people’s eyes that you can say that I’m a trans woman, a Moroccan woman, a Muslim, or whatever the fuck you see. But to myself, I’m just a hell of a woman called Lalla Rami,’ reads the quotation beneath one portrait of a woman wearing a slanted fez and blue suede high-heeled boots. There is no shame, either, in RIDIKKULUZ’s painting of Sultana, a Jordanian-Palestinian drag queen living in New York. The works respond to each other: Sultana then speaks for herself in the camp, cheesy video New York to Amman in which she stars, played on a loop in the Ballroom.

But the subject is so vast and multi-faceted that it feels constrained by the show’s small space. Two rooms are evidently nowhere near enough to begin to scratch the surface of what it means to be queer in North Africa and the Middle East today. It’s an ambitious introduction to some of the region’s most interesting and audacious artists – but an introduction nonetheless.

‘Habibi: Les Révolutions de l’Amour’ is at the Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris until 19 February 2023.