When Rachel Cohen’s first book, A Chance Meeting: American Encounters, was first published in 2004, it was widely acclaimed for its innovative structure in which the narrative unfolds like a game of consequences: in which, for example, a young Henry James is photographed by Mathew Brady, Mathew Brady photographs Ulysses S. Grant, and Ulysses S. Grant meets Mark Twain; or, to offer some 20th-century examples, we learn about James Baldwin’s great regard for the painter Beauford Delaney before getting into his more complicated relationship with his schoolfriend, the photographer Richard Avedon; and Richard Avedon photographs everyone who was anyone. Now republished by NYRB Classics, the book still seems bravura in form, but its account of more than a century of artistic endeavour by writers, painters, photographers, poets and choreographers carries new meanings, and some of the figures who were more marginal then are the figures we most want to know about today. Rachel Cohen, a regular contributor to Apollo, talks to Fatema Ahmed about what it is like to revisit a book after 20 years, and what it might mean to be an American artist.

Fatema Ahmed: You’ve said that you spent ten years writing the book and that it took quite a few of those years for it to settle into its final form. Can you explain where the idea first came from?

Rachel Cohen: There’s a biographical or autobiographical way to tell the story, and then there’s also a formal or an intellectual way to tell the story. I’m interested in biography, in the lives of writers and artists and especially in patterns of influence, the ways that one person’s life might influence another’s. I wanted in the essay form to learn to write a double portrait, to learn to think about two people – to think from more than one perspective at once, which is a common thing in fiction, but relatively uncommon in nonfiction.

Rachel Cohen: There’s a biographical or autobiographical way to tell the story, and then there’s also a formal or an intellectual way to tell the story. I’m interested in biography, in the lives of writers and artists and especially in patterns of influence, the ways that one person’s life might influence another’s. I wanted in the essay form to learn to write a double portrait, to learn to think about two people – to think from more than one perspective at once, which is a common thing in fiction, but relatively uncommon in nonfiction.

But then, autobiographically, I was a young writer. I had just left college. I didn’t really know what I was doing. I set out to drive around the United States because that’s a time-honoured way for a writer to figure out what they’re doing in American literature and, driving around, I was hoping to write some kind of travel narrative or about the state of America. But what I found was that I was collecting all these books of letters, I was visiting houses where different American writers had grown up, I was going to battlefields and looking at these different landscapes of US history. I was thinking a lot about the relationships that people had with one another. So that was the beginning point of working on what became this substantial book with 30 figures in it and 36 meetings that shows these long patterns of influence.

How did the form develop and what kept you going?

I’m a very tenacious person and I’m unable to let go of a book once it takes hold of me. But often my books take a long time for me to figure out, so I tend to try a lot of things that don’t work for a very long time. There was a version of it that my agent liked and sent out that was rejected by eight prominent editors – and then I wrote the book again. Mostly at that point people would say, okay, it’s not going to happen, I should move on to another project. But this had hold of me, or I had hold of it, so we went on together until I solved it to my satisfaction.

In each chapter, whether it’s a portrait of two people or when it’s three or more, depending on who the reader is, one of those figures might be much more familiar, and some people are more of a node or a connector than others. The photographers are nodes and not just because they’re capturing a visual record of other people; it’s about the encounter. Did Mathew Brady and Carl Van Vechten, for instance, start out like that in the book’s structure or did they become so later?

There are many things that writing can learn from portrait photography. For me, gesture is very important in understanding what a person is like. Sometimes from just a little gesture, you get so much of a sense of how that person hangs together. Mathew Brady staged his photographs – he was a great theatregoer and a lot of the people he photographed were actors and actresses. Similarly, Avedon loved the theatre and studied the way actors move. Steichen also loved sculpture – he loved Rodin’s sculpture of Balzac and took that over and over – and what that sculptor’s feeling was for the body and gesture became part of Steichen’s way of photographing.

In a way I was staging little scenes myself. By using the photographer as my eyes and the reader’s eyes, we could try to understand the gestures and movement of this other person as they came to be photographed. For someone like Henry James when he’s a little boy and being photographed by Mathew Brady, there was very good evidence that that moment of being photographed stayed with him all his life, because it became a central thing in his autobiography that he wrote decades later.

You were able to ask Richard Avedon about some of the portraits he took. What did that add to the book?

I knew somebody who knew him quite well, who took me to his studio once the book was going to be published. Avedon showed me negatives and talked about his process, which was wonderful. That confirmed some things that I had guessed, and it also allowed me to open up those parts in which he appeared. There was a very nice unlooked-for way in which the book produced the meeting, which allowed me to fold it back into the book.

I don’t know that anyone else thought to ask Richard Avedon about Mathew Brady.

That was thrilling. I was thinking that the way he was photographing in the 1960s felt so related to the 1860s so I brought it up and he told the story that I’ve included in the afterword. He went down to Washington, when he was very young, and saw the Mathew Bradys and was incredibly taken with them, and that was an early idea for him of what a photograph could be. Avedon, of course, went on to do portraiture that’s also thinking about American history, trying to photograph all the players as if history were a kind of theatre and you could photograph all the players – and that’s very similar to what Brady’s project was.

Mathew Brady was on a mission to photograph every famous American person of his time. You also write about Carl Van Vechten as a collector and about artists who are collectors, such as Joseph Cornell. Can you say more about this strand of collecting – of experiences or images or people – that runs through the book?

Many of the photographers especially were insatiable. There could never be too many people. They always wanted to meet another person and another person. Carl Van Vechten was especially like that. A lot of the people that Carl Van Vechten photographed were then a little bit on the margins and became quite forgotten for a long period of time – and are now the very people that everyone wants to know about. Anything you want to know about the Harlem Renaissance, the photograph is a Van Vechten. Anything you want to know about dance in New York for 25 years, it’s a Van Vechten. Every Black artist was photographed by Van Vechten. Every Black singer photographed by Van Vechten.

He had this strange way of photographing that I love, with these very vivid and strange fabric backgrounds that he felt kind of represented the people. In a way they’re kind of hokey – someone like W.E.B. Du Bois with this kind of jagged fabric behind him, with pinwheels or something – but in another way, it’s very lively and intimate because it’s just these two people in this setting that Van Vechten made up and their willingness to go and be playful with him.

Not all the encounters are successful. You include a really joyful photograph of Zora Neale Hurston by Carl Van Vechten, for instance, but also discuss his very stiff portrait of Willa Cather, which doesn’t work at all compared to the one by Edward Steichen, whom she clearly liked.

I think [Cather] wanted it burned, and it wasn’t burned but I didn’t put it in my book because I felt I would honour her feeling about it. Van Vechten photographed her in a giant hat and jewellery, as a kind of performance, but I think she felt exposed in a way that she didn’t like. Maybe it had something to do with the operatic side of her personality – opera and glamour and jewellery – and I don’t think she wanted that to be part of her public persona. That was her private affair in some sense.

Why were you so interested in the idea of the double portrait?

In each scene, I was putting two people together and having them respond to one another, and then each would go on to meet other people. That’s part of the formal construction of the book, but it took a while for me to figure out how to do that. What made it work was the wider net of people coming and going, so that it’s more like a choreography where you have different groups: four dancers dance, then they all leave, then two come back on to dance, then they leave and then another one returns, or stays and does a bit of a solo. That fluidity turned out to be necessary so that you could take advantage of seeing people at different times of life in different circumstances, so they could go off stage and 20 years could pass, and they could come back.

I was also interested in kind of recurring roles that people would play. Editors, portraitists, collectors, geographers: people who map the territory in one way or another. Those roles recur through the book and different people take them at different times. Sometimes even the same person has different roles depending on who they’re with.

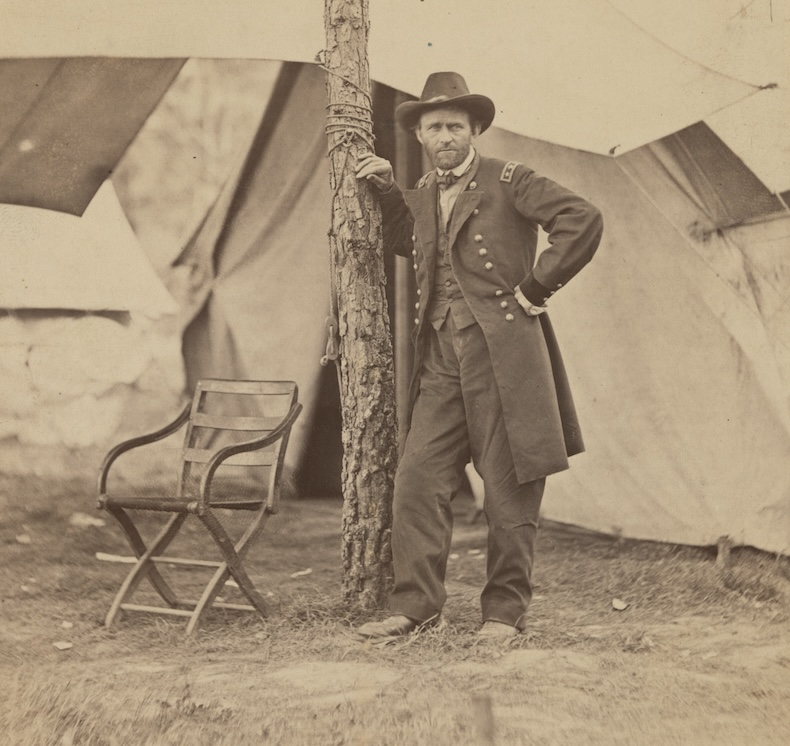

If I were naming the geographers, I would say: Gertrude Stein, Ulysses Grant – whose military talent was a geographical talent – Elizabeth Bishop the poet, who’s very, very interested in geography, and Willa Cather and Zora Neale Hurston, who are both thinking deeply about crisscrossing the US landscape and the kind of local cultures that are emerging and falling away in that landscape. That’s an unlikely group of people, but each is playing that role of sketching territory that’s necessary for everybody else.

Ulysses S. Grant (1864), Mathew B. Brady. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

It’s interesting how quickly the subjects in your book take to photography and to being photographed.

Photography was in some ways the first art form where the United States was sufficiently developed and capitalised that it participated from the beginning in that form. People got cameras very early and saw the commercial possibilities very early. I think in writing about Stieglitz and Steichen, I was trying to bring that out. They felt like photography is a place where we can have American fine art, we can do this. For painting, it wasn’t until Abstract Expressionism that Americans felt, okay, we’re actually leading the way and even ahead in terms of development.

The rise of photography also goes hand in hand with the idea of celebrity – and Mark Twain, who enjoyed being photographed, represents that in your book. You also mention the amazing detail of Willa Cather going to Twain’s 70th birthday party and there being foot-high plaster sculptures of him for the guests to take home.

It was a significant part of him that he was such a public person. He had this very big public persona in a way that our own celebrity culture makes us understand very well. You can imagine Andy Warhol having a party where he sent home statues of himself like that […] Anticipating Duchamp or other people who made happenings and who made events, that was part of what Twain was doing: staging his life.

Because of the period the book covers, there are many encounters between people making and promoting modern art. Stieglitz and Steichen and their gallery in New York are part of that. And when you write about the break-up of the Stein household in Paris: that Leo takes the Renoirs and leaves his sister Gertrude the Picassos, and they argue over the Cézannes, you’re also summing up a debate about modern art. I wonder how these figures – and that moment – seem to you now?

That node – Stieglitz and Steichen come to visit the Steins and take that home and present what they’ve learned in Paris in New York – that’s very fruitful. Many historians and writers are attracted to that moment, as I am, and it’s something that I continually revisit in different ways. My second book was about the critic and art historian Bernard Berenson, and he too knew the Steins. He too learned about Cézanne partly from them. I’ve taught courses about Cézanne’s painting and the way that you can see that painting entering prose: looking at Gertrude Stein and her writing around painting and at Rainer Maria Rilke and his writing about Cézanne, and at Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group and the way that Cézanne affected them. The personal and artistic reverberations from that nexus continue to be something that I’m ever investigating.

One artist Stieglitz didn’t give a show to in his gallery was the painter Beauford Delaney, who is an important figure in the book, but has become more important both to you and many others in recent years. In the new afterword you say that he’s the figure you’ve been asked to write about most in recent years. How has your view of him changed?

I included Beauford Delaney because of his close relationship with James Baldwin. Baldwin was already in the book, and I needed a side of Baldwin, an intimate side. I had him with Norman Mailer, who he was fighting with and who was mean to him, and I had him with Richard Avedon – and they had grown up together, but it was also complicated – and it was clear that there was a Baldwin who was present with Delaney who was not present with anybody else, or only with certain very intimate friends. I was in New York in a period when there weren’t Delaney shows all the time and I was a young writer. I didn’t realise that you could ask galleries if they would get their stuff out of storage and let you see it, so I just thought, well, I can see the reproductions. I knew that that limited what I could say about Delaney, I couldn’t write about the experience of the paintings, but that was what it was; there are always limitations in a book.

There had already been people doing Delaney shows – it just happened that I hadn’t been able to see them – but then, shortly after I published the book, there began to be a huge kind of upsurge in attention for Delaney and people recognised what a wonderful, complex painter he is. And then I found that I was seeing them a lot, there’s a great self-portrait at the Art Institute of Chicago that I can see all the time. There have been some special exhibitions that I’ve been able to travel to see. So now I’m quite immersed in the paintings of Delaney in thinking about his use of yellow, what abstraction meant to him. That’s a case where A Chance Meeting was the beginning of a relationship rather than the culmination of one. There are curators who are doing wonderful work and it’s been great to follow their discoveries.

Beauford Delaney (1953), Carl Van Vechten. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

The question of what it means to be an American artist runs through the whole book, which begins in 1854 and ends in 1967. How does that question seem to you now that your end point is feeling more remote than it must have done when you were writing it?

This is a book that was really written in the 20th century. I finished it in 2003, but a lot of the experience, and books that seemed like books to read, were from the 1990s and very early 2000s. I was interested in the way the figures were uneasy with the United States and the way they were at once trying to assert themselves as American artists and very uncomfortable.

In the afterword I say that many of them felt they had only become American because of violence or because their ancestors had been kidnapped, or because they had no choice, and many of them felt they could really only work when they were outside of the United States. Elizabeth Bishop went to Brazil to write her poems. James Baldwin went to Europe and other places. W.E.B. Du Bois left and never came back after he was made so unwelcome by the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was certainly a group of people who were always uneasy with American affiliation and American power structures.

The last line of the first chapter is that Henry James felt ‘a faint, persistent uneasiness’. Most of the people that I care about in life and in history, are in uneasy situations, can’t really get comfortable. All of that anticipates in some ways things that we continue to feel now, but it has intensified over the last eight years. And so, it feels different. It was my first book and there is a kind of optimism of youth, which I did feel, even though by nature I gravitate toward uneasiness. Nevertheless, there was a kind of – ‘these people can all meet and there can be a wonderful ebullience and maybe we will yet see the fruits of their labours’ – and I think it would be hard for me to write with that degree of optimism now. So, in that way, I’m glad I did it.

A Chance Meeting: American Encounters by Rachel Cohen is published by NYRB Classics.