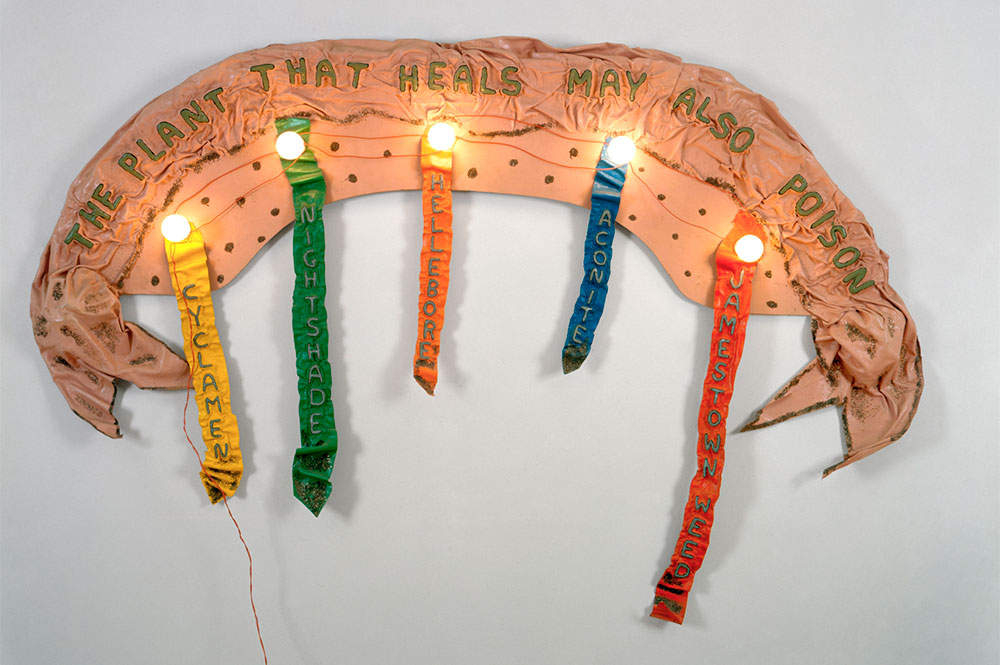

It is difficult to write about Ree Morton, as it would be any artist who died under a decade into her career. But Morton poses different challenges from, for instance, Eva Hesse, who was also born in 1936 and died seven years before the car accident that killed Morton in 1977. Hesse had gone to art school as a young woman, started making work in her early twenties and had articulate, well-connected friends (the artists Sol LeWitt and Pat Steir and the critic Lucy Lippard) to design and write her catalogue raisonné and thus ensure the shape of her legacy. Morton, in contrast, lived a full life as a mother of three before becoming a working artist in her mid thirties. The work has been displayed and written about before, usually in brief, when it appeared in group shows and in the scant solo exhibitions she has had since her death, but it has ultimately been seen by few. This means that when an exhibition opens like ‘The Plant that Heals May Also Poison’, the retrospective which originated at the ICA Philadelphia and which I saw at the ICA LA, it is both thrilling to see so much work assembled and disappointing to realise that certain key pieces, viewed on computer screens or read about, are missing.

One work which did not make it from Philadelphia to Los Angeles, Of Previous Dissipations (1974), has always been a favourite of mine, though I still have yet to see it in person. Surrounding a sweet oil painting of two blue roses is ballooning, rumpled orangey-pink celastic that looks like a curtain gone unnaturally hard. The celastic, essentially fabric-like plastic, is shaped into a little bow at the bottom, and on top, above the roses, Morton has painted the words ‘Of Previous Dissipations’ in delicate white bubble letters. I do not know exactly what this text means, but the tongue-in-cheek femininity of her materials suggests that the ‘dissipations’ may well be her rebellious indulgence in the decorative. The piece outsmarts its potential critics with its self-awareness. Morton’s sculptural work always feels in conversation, dependent on and inviting of reactions from others. (Morton’s friend, the artist Cynthia Carlson, has recounted how, when in 1974 the two were asked to be in a female-only faculty exhibition at the Philadelphia College of Art, while Carlson found the prospect too regressive, Morton said ‘she was going to do it with sticking it to them’ – Morton made Untitled (Bake Sale), a low table covered with fresh baked pastries and surrounded by celastic bows.)

Souvenir Piece (1973), Ree Morton. Fundação de Serralves, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Porto. © Estate of Ree Morton

At the ICA LA, the retrospective starts loosely at the beginning of Morton’s career as an artist, with her Wood Drawings (1971). When she made these small assemblages Morton was one year out of graduate school, and experimenting with little pieces of wood that she would draw on and hinge together. Hanging as a group, they look like members of a comic theatre troupe. Souvenir Piece (1973) pushes this method of working with drawing and wood further: a group of cut logs, other pieces of wood and rocks laid out on a green-painted table, with mismatched wooden sticks for legs. On the wall hang a series of minimal, playful, diagram-like drawings framed inside wooden crates – in one, four perfect dark dots bore into the paper beside the dotted outline of a pert, upright log. These earlier works most clearly evidence why Morton has been referred to as a ‘post-minimalist’: here she is, using raw materials and the sparse compositions redolent of Carl Andre and Robert Morris, yet without any trace of self-seriousness. In See Saw (1974), little glitter-covered white blocks circle around a stately raw wood teeter-totter.

See Saw (1974), Ree Morton. Courtesy Catherine and Will Rose; © Estate of Ree Morton

Yet when Morton began to abandon raw for painted wood, plus fabric, plastic and extra colour, her work became less a deviation from minimalism and more outright repudiation. In 1974, during a visiting lecturer gig, she made Bozeman, Montana, a work included here and an early foray into combining celastic and electricity. Two horse-shoe shaped, painted slabs of wood, each outfitted with five light bulbs (the electrical cords looping down to the floor), flank a series of multi-coloured celastic objects resembling glittery candy wrappers. Each bears text, in the all-caps bubble writing that would become Morton’s signature: the names of her students – ‘Mike’, ‘Richard’, ‘Curt’, ‘Manuel’ – sharing space with ‘beer’, ‘fish’, ‘pool’, ‘sky’. With its flashy lights, the piece is tongue-in-cheek garish, and also a record of the shared experiences surrounding its making. Through work like this, with its personal and distinctive voice, Morton was contributing to the conversation with other women artists, writers and scholars – Carlson, Marcia Tucker, Barbara Zucker – who were beginning to incorporate the personal into their public-facing practice in defiance of a male-centric establishment that treated the personal as unprofessional.

In one of the few interviews she gave from 1974, Morton recalled how the mostly-male faculty at Temple University in Philadelphia, where she went to graduate school, continually emphasised ‘commitment’, as if this is what an artist needed to be serious. She was not so sure, as the word had ‘a lot of implications that I couldn’t accept’. It is not that she was not lost in her work and committed to her craft. At its best, Morton’s work emanates an emotional spontaneity and a richness of knowledge that comes from intuition and lived experience.

Don’t worry, I’ll only read you the good parts (1975), Ree Morton. Courtesy Gail and Tony Ganz; © Estate of Ree Morton

Don’t Worry, I’ll Only Read You the Good Parts (1975) looks like a crumpled sun dress hung on the wall. It’s all yellow, except for the lines of black text that bear the work’s title, including a big flower (with a pink head) at the top left corner, right beneath what looks like a shoulder strap. The text reads as both entreaty and provocation – the kind of thing you’d say to a parent, child or partner dismissive of a story you love. In this show, the work hangs in a cluster, next to Let Us Celebrate While Youth Lingers and Ideas Flow (1975), a sculpture that wears its words on three thick pink celestial ribbons that wave vertically, energetically down across a painted blue-sky backdrop. Many have pointed out the uncomfortable prophetic quality of this work’s message, but it most significantly demonstrates Morton’s skill for unpretentiously compelling viewers to pay attention to what’s in front of them. She, like James Turrell or Mark Rothko, is asking us to stay in this moment, but far more lightly, with devil-may-care buoyancy.

The ICA LA is temporarily closed to the public due to the Covid-19 outbreak. For more information on ‘Ree Morton: The Plant that Heals May Also Poison’ (scheduled to run until 14 June) visit the institution’s website.