With its latest show dedicated to early modern sculpture, the Museo Diocesano di Padova has confirmed – to the detriment of its neighbours in Venice, which are so stubbornly devoted to exhibitions on painting – its status as the leading institution for the re-evaluation and appreciation of this particular branch of Venetian art. This trajectory began in 2013 with ‘L’uomo della croce. L’immagine scolpita prima e dopo Donatello’, followed two years later by a focus on three celebrated Donatellian crucifixes (from Santa Croce in Florence and the Basilica of Saint Anthony [the Santo] and the Chiesa dei Servi in Padua), which were admirably compared at close quarters. Furthermore, the exhibition under review, as well as those that preceded it, has benefited from generous contributions by banking foundations and the local community, which – in response to the various appeals of the museum’s Mi sta a cuore (‘It matters to me’) fundraising initiative – has made possible the conservation of four of the works shown here (including the relief illustrated above).

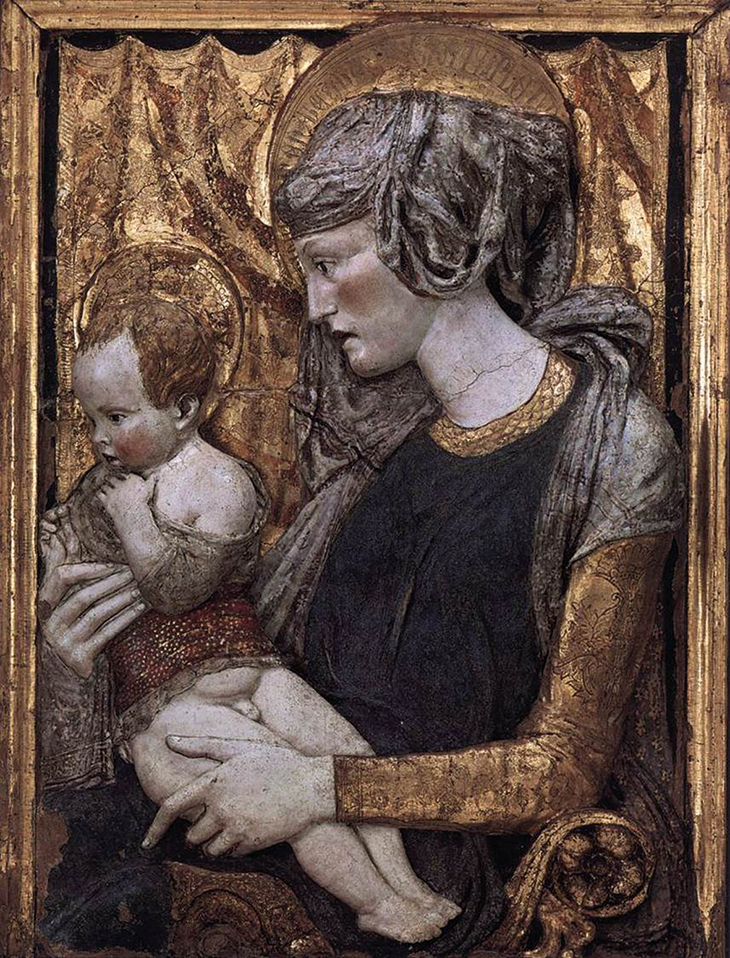

The focus this time is on terracotta, a medium that flourished in the Veneto in the mid 15th century in the wake of Donatello’s appearance in the region. Curated by Andrea Nante, director of the Museo Diocesano, and Carlo Cavalli – and with support from a committee of experts and the Università degli Studi di Padova – the exhibition opens with the inescapable Donatello, whose example is well represented by the highly lyrical Madonna and Child from the Louvre, the sole international ‘guest star’ among the assembled works. Its execution dates to around 1440–45, three or four years, that is, before the arrival of the Florentine artist in Padua, or at the very latest during the first period of his stay in the city. As Francesco Caglioti emphasises in the catalogue (which also includes his in-depth discussion of Donatello as coroplast, or maker of terracottas), its ‘supreme modelling’ and ‘disruptive invention’ make this terracotta a key turning point in the succession of devotional images produced by the versatile Tuscan sculptor. Compared to his juvenile works, here Donatello ‘achieves in a mode now mature and linked to ancient models […] that triangulation between Mary, Jesus and a third, invisible person’, located beyond the relief but no longer corresponding to the faithful beholder – who, from having previously been an actor, becomes simply a witness to the entire scene. During his decade of activity in Padua, a period divided into work on the equestrian statue Gattamelata, the bronzes for the Santo, and the wooden crucifix for the Chiesa dei Servi, the Tuscan artist also modelled ‘many […] figures in clay and stucco’, as described by Giorgio Vasari in the Lives. As evidence of this, the exhibition includes two Madonna and Child reliefs, one in polychromed papier mâché, derived from a model by the sculptor known as the ‘Verona type’, of which some 25 copies are extant.

Madonna and Child (c. 1440–45), Donatello. Musée du Louvre, Paris

After Donatello’s departure from Padua in 1453, Giovanni di Francesco da Pisa imposed himself on the city as the direct spokesman of his nourishing example, to be followed by a Paduan, Bartolomeo Bellano, who had returned to the Veneto from Florence in around 1467–68, and whose expressive figure of a mourner can be admired here. Without the presence of the Madonna and Child from the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, created by Giovanni in around the mid 15th century, the exhibition’s organisers have substituted for it a 20th-century copy from Lissaro di Mestrino, from the church where the work now conserved in Texas was to be found until 1902. All the same, to understand the greatness of this sculptor, and to grasp how his ‘Donatellian declension of mannerism’ (Caglioti) proved so essential to artists of the following generation, on leaving the Museo Diocesano the visitor can make for the Chiesa degli Eremitani and admire its magnificent Pala Ovetari, which the artist made around 1448–50. It is the Virgin with the small figure of Jesus at the centre of this last work – together of course with Donatello’s bronze for the Santo – that almost certainly influenced the recently arrived Giovanni de Fondulis, the sculptor who by sheer number of works is, together with Andrea Riccio and his moving Lamentation, the real protagonist of the entire exhibition.

Madonna and Child Enthroned (c. 1468–70), Giovanni de Fondulis. Chiesa di San Nicolò, Padua

On to Giovanni de Fondulis, then. Unjustifiably missing, unfortunately, is the group of The Baptism of Christ between the Prophets David and Isaiah, from the Museo Civico di Bassano del Grappa, and originally from the local church of the Baptist – and the only documented work by the artist for which we have a certain date: 1474. Had it been present in the exhibition, it would have provided a touchstone against which to evaluate the evolution of the artist’s style and, at the same time, a useful point of comparison for testing out the new attributions put forward here – some of which remain a little doubtful. De Fondulis was born in Crema in around 1435, but little is known of his early artistic activity before his arrival in Padua, where he was certainly present from at least January 1468 (as Marco Scansani discusses in the catalogue). At that point he was 33 – a trained sculptor, then, already in possession of his own artistic syntax. The Madonna and Child Enthroned from the Abbazia di Santa Giustina and a polychrome work of the same subject from the Chiesa di San Nicolò are thought to be the first two terracottas created by him in the city. They are works of exceptional quality, in which the lesson of Giovanni di Pisa, and therefore of Donatello – though less that of Pietro Lombardo, which is invoked by Scansani – is clearly perceived in the treatment of the drapery, which clings so tightly to the figures that it is as if they have just ‘emerged, fully clothed, from water’ (Caglioti). From the 1480s onwards, De Fondulis seems to have conformed to that classical language that also characterises the paintings of Giovanni Bellini, with their pensive Madonnas in noble poses, with soft faces on which falls a peaceful light (as seen here in the Madonna and Child Enthroned from the Istituto Suore Maestre di Santa Dorotea di Padova).

There are eight terracottas attributed to De Fondulis in the exhibition, many of which, as discussed, hail from Padua and the surrounding region. That’s not a secondary detail: besides placing local artistic heritage in focus – and there is a useful ‘Atlas of Paduan Renaissance Sculpture in Terracotta’ at the back of the catalogue – the organisers have effectively turned the show into an unmissable opportunity. It would have been more challenging for the average visitor to get to the small towns – Camponogara, Due Carrare or Pozzonovo – than to reach, say, Paris, Florence or, at least before the quarantine began, the easily accessible city of Padua.

‘A nostra immagine. Scultura in terracotta del Rinascimento da Donatello a Riccio’, at Museo Diocesano di Padova, reopened to the public on 20 May.

From the May 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.