As you enter Mazzoleni London a shiny black curved form greets you. Four decades have passed since a white version of the same work welcomed visitors to Milan’s famous Galleria del Naviglio, but I imagine the effect is very similar. You immediately feel drawn into a spatial relationship with the undulating curves. This concern with space is central to the work of Agostino Bonalumi (1935–2013), a pivotal figure in post-war Italian abstraction. Like his friends Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani, Bonalumi blurred the boundaries of painting and sculpture with shaped and manipulated monochrome canvases. Bonalumi’s work has been shown in London at Robilant+Voena in 2013, and more recently featured alongside that of Manzoni and Castellani in international exhibitions on Azimut/h and the Zero Group. His profile and prices have also been on the rise in major auctions of Italian art in London. However, until this exhibition and the accompanying catalogue raisonée, his sculptures have received little attention.

The exhibition at Mazzoleni, the latest Italian gallery to open a Mayfair branch, brings Bonalumi’s paintings and sculptures – notably he insisted upon a distinction between the two – into dialogue. Close to the aforementioned sculpture Nero (1969) hangs a painting from the subsequent year; the same colour and materials are used to create a relief with embracing curves. In the subsequent room Rosso (1969) protrudes much like the Nero of the same year, but its wall-mounting enforces a degree of separation from the viewer. In the downstairs gallery are three smaller and more recent sculptures, two Blu and a Giallo, whose curves develop out from what look like stretchers for canvas paintings.

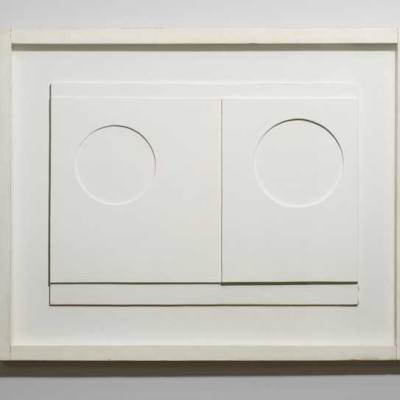

Rapporti (1978), Agostino Bonalumi, courtesy Archivio Bonalumi and Mazzoleni London

Once a student of mechanical design, Bonalumi experimented with industrial materials as much as traditional artistic ones. Fibreglass and metal sheets are coated with brightly coloured enamel; a material called ciré is stretched and sewn into the form of a painting. In a particularly rare work, Rapporti (1978), Bonalumi uses glass to interrogate the relationship of matter and light, the impetus behind his material experimentation.

Bonalumi matched forms, materials and colours, and while he has an immediately recognisable style, his work is not repetitive. However, in the last decade of his life he cast in bronze forms previously made in less-reflective materials, to discover how a polished finish would change them. In his paintings too, light is all-important. In Rosso (1973) geometric ‘extroflexions’ distort the canvas at different angles to create shadows; the form created and the form implied by the shadows are contradictory.

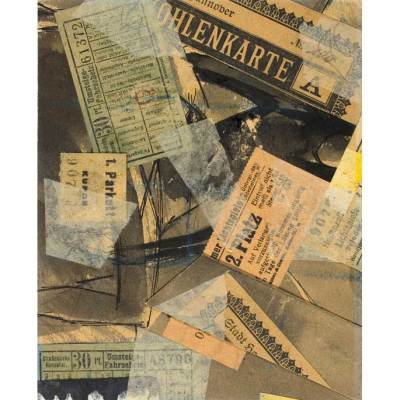

Installation view: ‘Agostino Bonalumi – Sculptures’, Mazzoleni London. Courtesy Archivio Bonalumi and Mazzoleni London

Bonalumi’s exploration of space and disregard for the picture plane highlight his debt to his forerunner Lucio Fontana, but his fascination with dynamism indicates a continuation of Futurist ideas too. The sensuousness of the forms, and above all their tactility are reminiscent of Barbara Hepworth and Lynda Benglis – two artists receiving retrospectives in the UK this year. Bonalumi’s legacy is clearly apparent in the forms and finishes of Anish Kapoor. Like all these artists, works by Bonalumi need to be experienced first hand, and with no works by him in UK public collections, this is a rare and exciting opportunity.

‘Agostino Bonalumi – Sculptures’ is at Mazzoleni London until 4 April 2015.

Related Articles:

‘AZIMUT/H’ at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection (Rosalind McKever)

First Look: ‘ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow’ at the Guggenheim New York (Valerie Hillings)

Review: Lucio Fontana at the Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris (Emma Crichton-Miller)

Rule Breaker: Lynda Benglis (Imelda Barnard)

London’s Italian art invasion (Rosalind McKever)