This review of The Rising Down: Lives in a Sussex Landscape by Alexandra Harris appears in the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

When faced with writing about the Victorian age, the critic and essayist Lytton Strachey pictured himself rowing out over a vast ocean of material in order to ‘lower down into it, here and there, a little bucket, which will bring up to the light of day some characteristic specimen, from those far depths, to be examined with a careful curiosity’. I suspect that if Alexandra Harris had been in Strachey’s boat she would have left him to his fastidious scrutiny, plunged into the water and swum down to find out what life was like from the specimen’s point of view. As she remarks in The Rising Down, her deep dive into West Sussex’s past, her ambition was not just to ‘watch the people passing […] but for just a moment to look with them’. The result is a remarkably original project of imaginative rehabilitation.

In The Rising Down Harris writes the biography of the places in which she grew up – contained within a roughly triangular area with the village of Pulborough at the top, stretching down to Arundel and across to Chichester. A more conventional book would have focused on the big names who stayed for a while or settled there – John Constable, Ford Madox Ford, Ivon Hitchens. All are present and paid close and fruitful attention, but this book’s real centre of gravity is to be found in obscure figures. Harris’s ambitious project is to resurrect lives and their contexts from small prompts: a name inscribed on a memorial brass; a 17th-century water bailiff’s account of the river Arun; records of a Polish school established in Monkmead Wood in the 1940s. Her book bristles with perspectives: she looks at Sussex from a boatman’s-eye-view, a warrener’s, a young widow’s, a geologist’s, a swan’s. As she explains, ‘I let each chapter grow from a moment of startled noticing or finding: a document or a painting, a date stone or a lump of concrete, a voice overheard. Each suggested a different kind of exchange between local lives and wider worlds.’ Harris sets out to explore ‘the multiple dimensions of time and place that make up the apparently fixed scene of the present’, because, as she points out, human beings can never allow anywhere to be simply itself – our individual memories and vantage points see to that.

In The Rising Down Harris writes the biography of the places in which she grew up – contained within a roughly triangular area with the village of Pulborough at the top, stretching down to Arundel and across to Chichester. A more conventional book would have focused on the big names who stayed for a while or settled there – John Constable, Ford Madox Ford, Ivon Hitchens. All are present and paid close and fruitful attention, but this book’s real centre of gravity is to be found in obscure figures. Harris’s ambitious project is to resurrect lives and their contexts from small prompts: a name inscribed on a memorial brass; a 17th-century water bailiff’s account of the river Arun; records of a Polish school established in Monkmead Wood in the 1940s. Her book bristles with perspectives: she looks at Sussex from a boatman’s-eye-view, a warrener’s, a young widow’s, a geologist’s, a swan’s. As she explains, ‘I let each chapter grow from a moment of startled noticing or finding: a document or a painting, a date stone or a lump of concrete, a voice overheard. Each suggested a different kind of exchange between local lives and wider worlds.’ Harris sets out to explore ‘the multiple dimensions of time and place that make up the apparently fixed scene of the present’, because, as she points out, human beings can never allow anywhere to be simply itself – our individual memories and vantage points see to that.

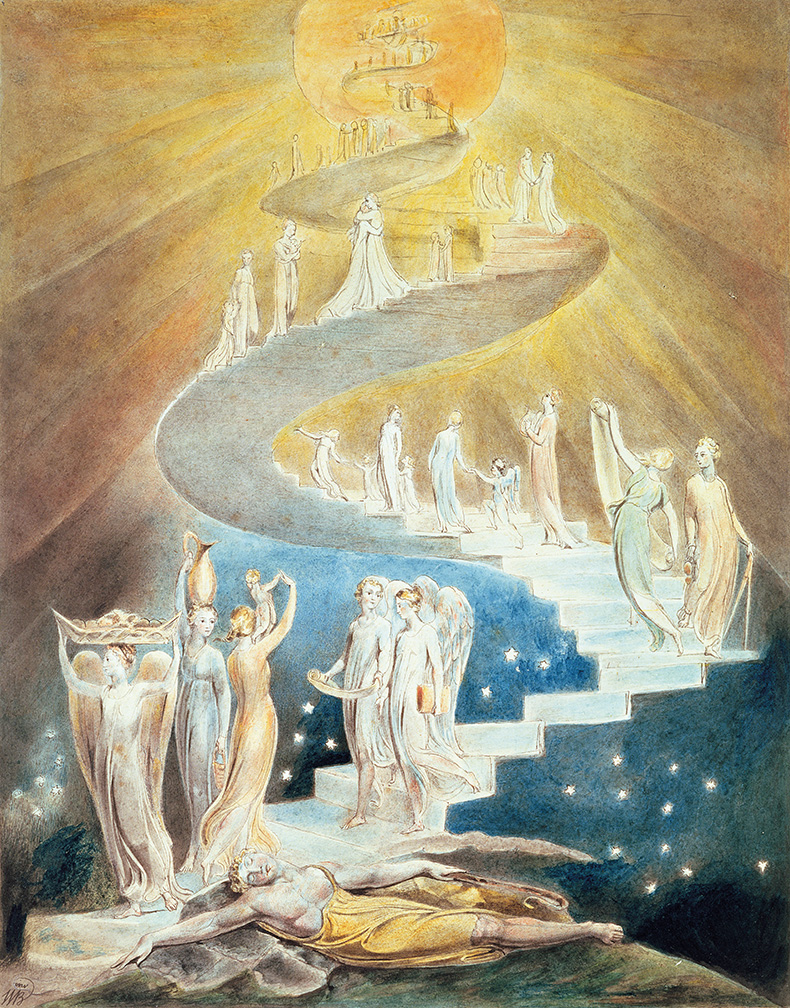

William Blake, who could find a world in a grain of sand and for whom the past was a living entity, is a kind of genius loci of The Rising Down. Harris’s chapter on him is among her best. Invited to Sussex by the poet William Hayley, this Londoner lived in the village of Felpham from 1800–03 and Harris shows us local landscapes and the Chichester townscape through his eyes (the ‘Rocks of Bognor’ make an improbable appearance in Milton) while also addressing his experience of Felpham as a ‘site of cosmic eventfulness’ (‘Away to Sweet Felpham, for Heaven is there; / The Ladder of Angels descends thro’ the air’). Counter-intuitively but persuasively, she describes Blake as being ‘among the most radically local of all Romantics’ and makes brilliant sense of his overlaying of everyday surroundings with the supernatural – his account, for example, of meeting the spirit of Milton on his garden path – by drawing comparisons with 15th-century Netherlandish paintings in which it seems quite natural for biblical scenes to take place in modern settings.

Jacob’s Ladder (or Jacob’s Dream) (c. 1799–1807), William Blake. British Museum, London. Photo:

Among the other artists who walk into Harris’s viewfinder is the landscape painter George Smith of Chichester, whose pictures transformed Sussex into a fashionable Italian campagna and bathed it in honeyed light. Constable, on the other hand, sought to represent the landscape as it looked under English skies; his passion lay in working away at places he knew intimately, excavating ever deeper over time. Having travelled so little in his life, when he visited a friend who showed him around the area he was astonished by Sussex’s woods and hills: ‘I never saw such beauty in natural landscape before,’ he enthused. Even so, Constable was a restless traveller when compared to Hitchens. Having moved to a plot near Lavington Common during the war, Hitchens settled down to paint the woods, streams and plants of his immediate surroundings, an activity that absorbed him for nigh on four decades. As Harris astutely puts it, he ‘didn’t think a tree was any less interesting for being in the same spot every day’.

Arundel Mill and Castle (1837), John Constable. Toledo Museum, Ohio

For all its intense focus on locality, The Rising Down has a stake in the wider world: Harris makes room for the voices of those who emigrated from Sussex villages to Australia and Canada, who, when writing home, compared the new landscapes they encountered with the South Downs. Likewise, she introduces the stories of those who arrived from elsewhere, bringing fresh ideas and perspectives. During the Second World War the anti-colonial activist and future prime minister of Kenya Jomo Kenyatta worked as a labourer on a farm near Storrington, lectured in village halls and grew vegetables on a plot modelled on an East African shamba.

So does the book’s bold experiment in life- and place-writing work? Although The Rising Down is beautifully written and deftly orchestrated, I was conscious at first of a slight muffling of the exuberance and wit that animate Harris’s previous books, as though she had been treading carefully as she negotiated this strange yet familiar territory. There was no need: in The Rising Down Harris pioneers a beguiling and exciting new way of thinking and writing about the overlapping strands of time and place that will doubtless inspire other writers to follow her lead. Whether all her readers will be as entranced by the obscure figures she resurrects as the well-known ones is a moot point; these people are worth thinking and writing about and I suspect that no one but Harris could do it so well. The Rising Down is an important book, and it feels like one that will continue to rattle around the mind and invite re-readings far into the future.

The Rising Down: Lives in a Sussex Landscape by Alexandra Harris is published by Thames and Hudson.

From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.