Robert Rauschenberg’s famous pronouncement that he wanted to work in the ‘gap’ between art and life says much about the nature of his art, which was often collaborative, three-dimensional and interested in the wider world. It also, however, says something about his mission as an artist, a large part of which revolved around his sincere belief that artists could drive social change. It was this way of thinking that led Rauschenberg to set up his own foundation in 1990, which has since grown to be one of the largest and most influential of its kind in the world. It operates out of the artist’s old studio on Lafayette Street, New York, as well as in the house he moved to in Captiva, Florida, in 1970, and is known for its forward-thinking approach to art and culture. As well as holding artist residencies at both its main locations, managing the Rauschenberg estate and providing grants to artists and cultural projects, it has in recent years pioneered a radical fair use image policy and embarked on an ongoing catalogue raisonné, which will be published in instalments and will be fully digital and free to use.

Rauschenberg was born 100 years ago this month. The foundation has been busy working with museums and galleries from Houston to Hong Kong on a slate of exhibitions this year and beyond. Courtney J. Martin, who became executive director of the foundation in 2024, recently talked to Apollo over Zoom about her vision for the foundation, the significance of the centenary and, most importantly of all, why she loves Rauschenberg.

How did this job come about and why did you want to take it?

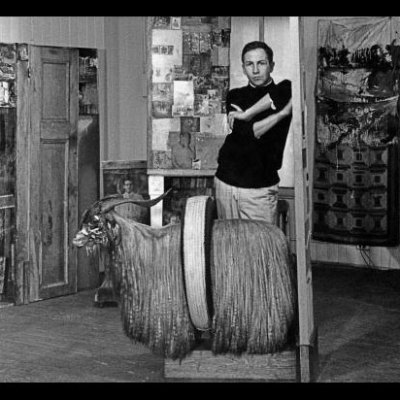

I was an academic for a number of years, and I’m trained in the 20th century. Rauschenberg, for me, was an incredible figure for a host of reasons. If you look at Rauschenberg in the late ’40s and early ’50s, he seems to be going in one direction: he’s painting, and he is interested in tonal qualities, and then he’s interested in the space between the two and three dimensions, which results in the Combines. He gets to this point, and then he just makes a left turn and suddenly he’s performing with Merce Cunningham, he’s choreographing and stage designing with Paul Taylor and with Cunningham, and then he gets involved with the Judson Dance Theater and Trisha Brown. He makes the costumes, he makes the sets, he thinks through a way of being in public as a performance. For a lot of people who were looking at that work at the time, it might have been confusing that this person who was so clearly an amazing painter, and innovative in terms of moving the painting out from the wall – now he’s dancing. When you get to the ’90s, everyone is talking about installation, post-studio practice, being a multi-dimensional artist and so on. Rauschenberg already showed us how to do this in the late ’50s; he was the forerunner of that way of working.

That seems like a long-winded answer, but when I was approached about the role, I think I said everything that I’ve just said to you. The recruiter said, ‘So are you interested?’ And I was thinking, ‘Yes, oh my god, it’s Rauschenberg. Of course I’m interested. Everybody’s interested. Look at what he’s done for the art of our time.’

You were director of the Yale Center for British Art before you took this job. How have you found the switch?

Every job I have ever had brings me closer, at that moment, to working for art and artists. That’s always my goal. The foundation, in many ways, reflects Rauschenberg as a whole person. Early in his career, in 1963, he set up the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, with John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns and others, which continues to fund artists. Seven years later, Rauschenberg, who was incredibly generous to everyone, started a foundation called Change, Inc., which was funded from the proceeds of the sales of his art and provided artists and cultural workers with small-scale funds for emergencies – with very little bureaucracy and very little oversight. It was life-changing for a lot of people: Gordon Matta-Clark, for one, got healthcare through Change, Inc.

I can’t separate what our work is every day from what his work was every day. He was doing just as much philanthropy as he was art, because he didn’t see them as being unrelated. So when this position was presented to me, I thought of it as a chance to inhabit Rauschenberg, in a sense. I spend a lot of time wondering if I’m doing things in a way that Rauschenberg would have done them.

The foundation itself is known for being quite innovative, particularly around the introduction of the fair use image policy, as well as the ongoing digital catalogue raisonné. Could you talk me through the ethos behind these two projects?

For us, fair use comes out of Rauschenberg’s own generosity. He would never have charged for images, so we don’t either. There are even many commercial instances where we do not charge because we are so much more interested in having the work available publicly for more people to see. As a writer, I know that you cannot limit your thinking around what images you can afford. You just have to keep going. So we don’t ever want to be in the way of that.

The same goes for the catalogue raisonné. We’ll release our first volume next year, which will be digital and free to access. Our goal is to have all of that information out there for anybody without any kind of barrier. I think it’s also realistic: if you really want people to read about something now, you would have to be on a digital platform. And we’ve just taken the paywall out of it.

What are you most proud of achieving or implementing since you’ve been at the foundation?

Right now I’m really proud of the current exhibition at the Guggenheim. It overlaps with the Rashid Johnson and the Carol Bove shows, so I’m really excited about the idea that perhaps younger people who are coming to see both of those artists will get to know Rauschenberg. Rauschenberg had a major retrospective in 1997 at the Guggenheim and they’ve long been a collector of his work, but this will be the first significant posthumous show that really goes back and looks at that early period.

Can you talk me through the process of putting on a Rauschenberg show?

Generally institutions approach us, and these conversations can go on for years. It starts with a curator somewhere calling the foundation and saying, ‘Hey, what about this?’ And because we have a library and an archive, we can fully support the research for an external exhibition. You can come here, you can look at things, you can see works in the collection. You can, you know, find supporting information, but we can also then maintain a dialogue with you after you’ve left, because we have all the material as well.

Why do you think the foundation has been so successful, both financially and in terms of some of the projects it’s been able to embark on?

I think it’s down to Rauschenberg the person – and I don’t mean that to be cheesy, but I do think that he had a lot of vitality. The building that I’m in right now was his home and studio. He bought it in 1965 and even though he moved to Florida primarily in 1970 it remained his headquarters. Everybody that he knew could come here and work here. We still work with that same sense of cohesiveness and collaboration, and we’re all excited about it. I have staff who started their careers as Rauschenberg’s studio assistants and they come to work every day talking about what Bob would have wanted.

I also think that we have been successful because we have a mission, which is both about supporting artists and about supporting Rauschenberg’s legacy. The legacy piece is straightforward, but supporting artists changes constantly, because artists need different things at different times. Earlier this year artists in L.A. and on the East Coast needed support because of the fires and the floods, and we had to respond as quickly as possible.

There are so many threats to both public funding and to cultural expression at the moment, especially in the United States. How do you view the state of artist-endowed foundations at the moment?

We fall under a large umbrella, as a vehicle that comes out of the US government, and that’s what allows us to function. But there are so many younger artists setting up their own foundations, such as Julie Mehretu and Kara Walker recently. Artists who have a degree of success deciding to step back and ask, ‘what can I give to other artists?’ is incredibly important. Rauschenberg did that, and we are now something of a model for how to do it. A lot of artists come and talk to me about how they might set up a foundation, and that’s great, but I think the first step is them recognising that they have the ability to do it in the first place. I don’t think that art school or MFA programmes tell you to do that. It has to come from the inside.

Have you noticed an increase in foundations being set up?

No, I think it started a long time ago – I look back even more than a decade ago, with Mark Bradford starting Art + Practice with the money that he received from his MacArthur Genius Award, for example. I think it starts from a place where artists feel gratitude, and they want to move that gratitude forward. I think it’s slightly different in the UK, but American artists tend not to expect state help, so as a consequence there’s already more of an entrepreneurial spirit.

We have a funding body inside the foundation called the Artists Council, which is an anonymous group of artists who change over time and who make funding recommendations based on a host of priorities that they decide themselves. We allow them to do it because we think it’s really important for artists to have a say. And many of the artists who have been involved in the Artists Council are also now privately putting their own money into civic causes.

There are always things we can improve on, but instead of always talking about the fragility of the state of the arts in this country, I want to get to a space where we talk about art as a strength and artists as real innovators, because they are. The foundation has the ability to move that conversation forward and the opportunity to join with other artists’ foundations so we don’t have to go this alone.

For the centenary, there’s not really one massive monographic show at a major museum; there seem to be lots of medium-sized and smaller shows around the world, often focusing on one narrow aspect of his career. Why do you think that is?

Some of this is also coming out of a post-pandemic way of thinking. We have to be mindful of climate change, for example, so we have a good number of shows that allow multiple audiences to see different things at different places, as opposed to one big show that you’d have to travel to see.

It’s also about the variety of Rauschenberg’s work. Each of the shows is either medium-specific or topical. There’s one at the Museum of the City of New York on Rauschenberg’s photography – we’ve not had a major photography exhibition in over 20 years. So that will be a new discovery for people. Whereas the show at the Grey Art Museum looks at Rauschenberg’s environmentalism. Then there was our collaboration with the fashion designer Jason Wu, which was a fashion show at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. None of us knew what to expect, but Jason became so interested in Rauschenberg and he left almost as an expert.

For me, Rauschenberg is one of those artists who is still slightly underrated, especially in the UK. Do you agree, and why do you think that might be?

Last year the painter Alex Katz won the National Medal of Arts, and we had done an oral history with him some years ago. We know that he knew Rauschenberg. We thought we knew everything that he wanted to tell us about Rauschenberg. He accepts the award on national television and he starts naming his influences, and the first person he names is Rauschenberg, and he talks about how Rauschenberg was so important to him. I got in touch with him, and I said, ‘Where did that come from?’ And he said, ‘It’s always been there, it’s just that now I can finally see it.’ Their work looks nothing alike. They never collaborated, they didn’t go to school together. What it showed me is that Rauschenberg is so important for a lot of people and he helped define a way of working, and I think that sometimes people become aware of it because their own practice develops to such a degree that they can step back and see it differently. This is also one of the reasons that I’m so keen to bring Rauschenberg to younger audiences, because I think they’re always seeing the effects of his work, even if they don’t necessarily know that that’s what they’re seeing.

Rauschenberg did do a lot of travelling and has clearly had an effect abroad – for instance through his Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Exchange (ROCI) works, which were shown in London last year. Can you tell me a bit about that aspect of his career?

In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, when people were first looking at the ROCI works, they weren’t sure what he was doing. Why was he going to all these countries and making work in different countries? And now you think, well, of course he wanted to go. He went to Cuba and the USSR at a moment when the United States didn’t have good diplomatic relationships with those places, and I think that the reason he wanted to go to those places was because he felt that if he could break through all the noise and get down to actually meeting artists, there was a different story to be told. Some of the places he went to didn’t have an art school, but he knew that there was a practice there. What might be taken as almost a kind of naivety is actually his understanding that, no matter what’s going on in the big picture, artists are still working on the ground. He knew that being an American allowed him to break through to that – and that is imperialism, absolutely – but he’s using that to actually get closer to something real.

Do you have a favourite work by Rauschenberg?

I have several favourites, but there’s one work from his Jammers series called Trowel (1976), which is currently on view in the exhibition of Rauschenberg’s fabric works at the Menil Collection. It stretches along a wall, and it comes out askew to make an isosceles triangle. Then there is a piece of it that extends out into a bag that has sand in it. It’s basically just a sheet and a piece of string. But it’s a statement about how we all inhabit space, and I think it has a philosophical charge to it – as someone who comes from a background of sculpture studies, I think that when you change space you change the viewer’s whole understanding of their world.

What do the next few years look like for the foundation?

We have more shows coming up this year, including ‘Robert Rauschenberg and Asia’ at M+ in Hong Kong, which opens in November. We also have some new funding announcements for the end of the year, which will be about us finding new and better ways to support artists. That’s always exciting for me.

For more information about the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, visit www.rauschenbergfoundation.org