From the December 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Perched atop a hill at the base of the Apennines, halfway between Bologna and Pistoia, stands one of the strangest buildings in Italy. Begun in 1850, and continually under construction for the next 70 years, the Rocchetta Mattei is Italy’s Hearst Castle, its Xanadu: a mishmash of medieval and Moorish, European and Near Eastern, decked out with gold-leafed onion domes, minarets, sundry towers and turrets.

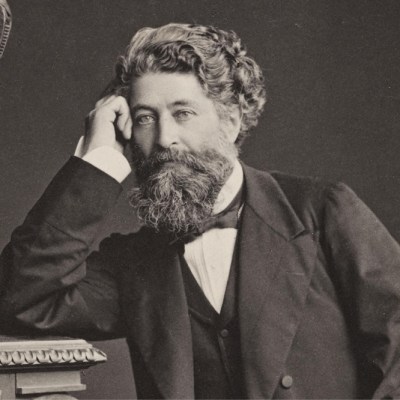

This architectural caprice was buit by Count Cesare Mattei, the scion of a trading family who was ennobled by the pope in 1847 for his contribution to the defence of the Papal States against Austria and who, after a brief foray into Risorgimento politics, retired to his books. After his mother died of cancer, Mattei dedicated himself to finding alternatives to the medicine that had failed her. He became a champion of the therapeutic potential of the vital energy stored in plants, founding what he called electro-homeopathy – a method of drawing ‘liquid vegetable electricity’ from leaves, flowers, fruit and seeds that, Mattei claimed, could cure everything from stomach worms to cancer.

Despite what one contemporary British doctor called ‘its utter idiocy’, electro-homeopathy found adherents across Europe (Dostoevsky alludes to it in The Brothers Karamazov) and, though the count died in 1896, his business was producing tinctures until 1969. A French edition from 1925 of one of Mattei’s books takes its epitaph from Madame de Staël: ‘Most of the great discoveries seemed absurd at first.’

The Rocchetta, which is now owned by a private foundation and managed by the local municipality, opens only at weekends; perhaps the nearby village of Riola is busier during the week, but it is completely deserted when I arrive on the regional train from Bologna on a chilly Sunday in October. The place feels alpine and northern, although it’s smack in the middle of Emilia-Romagna. The Rocchetta sits on the site of the 12th-century castle built by Matilda of Tuscany, a small remnant of which survived when Mattei chose the location. He began with the ambition of creating a medieval fortress, and built some crenellated battlements and large cylindrical towers. He then went through a brief gothic phase before adopting an evocative though somewhat cartoonish Moorish style.

The entrance is at the north-west corner of the castle wall, through a small gate, topped by a gently pointed arch; you then mount steep steps made of large stone slabs, and pass beneath a second arch, taller and pointed like a flame (a kind of exaggerated ogee), on the inner face of which is a relief of a lion’s head. This leads to a mushroom-shaped wooden door decorated with four technicolour discs with stars at their centres. A short tunnel through another Moorish arch – supported by two 12th-century carvings in Verona stone, one of a demon and one of a hippogriff – opens into a courtyard that, although dominated by a tall, spindly minaret, features a fountain that once served as a baptismal font in the Lateran basilica of San Giovanni in Rome. These spolia, and others sprinkled throughout, add to the geographic and chronological confusion.

The first step on the carefully guided tour – the only way to see the Rocchetta after it officially reopened in 2015 after 10 years of restoration (which is ongoing) – is the count’s chapel, which is up a narrow stairway on the west side of the castle. The sanctuary is, naturally, a miniature reproduction of Córdoba’s Mezquita, with M.C. Escher-like arches that seem to stretch into infinity.

The chapel in the Rocchetta Mattei. Photo: Roman Robroek/Alamy Stock Photo

Next stop is a scaled reproduction of the Lion Courtyard of the Alhambra, featuring a lion fountain in the centre, colourful tiles tessellated in geometric patterns along the walls, and, over the exterior-facing face of the portico, stone inscribed with Arabic calligraphy. The inscription is a direct copy from Owen Jones’s The Grammar of Ornament (1856), which Mattei ransacked for the extensive ornamentation, painted, plastered, and carved, throughout the castle. (Mattei seems to have been inspired, too, by the Arab craft and architecture displayed in 1851 at the Great Exhibition in London. An Anglophile, he even dedicated a room at the Rocchetta to Queen Victoria.) From there, you proceed through a number of internal chambers, many decorated in the Liberty style by the count’s adopted son after his death. Almost all of Mattei’s private rooms are roped off – a shame, since the best book on the castle, by an English expat architect, suggests that these contain some of Rocchetta’s most extravagant interior decoration.

Though my tour guide made little mention of electro-homeopathy, it’s impossible to separate the count’s medical entrepreneurship from his castle, which was built, in part, as a sanatorium – and as a kind of visual proof of his own legitimacy. But under scrutiny, the Rocchetta turns out to be not much more real than electro-homeopathy. Take the chapel: from the gallery above the altar, where the count lies buried in a colourful glazed sepulchre, produced to his specifications by the Minghetti factory in Bologna, it becomes clear that the marble arches are actually painted wood. The ceiling, which from below appears as intricately carved woodwork, is in fact made of trompe l’oeil canvases. In the second-floor ‘Red Room’, named for the red cloth that once covered its walls, one half of the vaulted ceiling looks like Fingal’s Cave, with hundreds of pointed cubic stalactites of varying heights, stained brown to look like wood. These are, in fact, made from newsprint papier-mâché. It’s fitting that the director Marco Bellocchio used the castle as the setting for his adaptation in 1984 of Pirandello’s Enrico IV, about a 20th-century aristocrat who, after falling from his horse, becomes convinced that he’s the Holy Roman Emperor.

The German occupation of the Rocchetta during the Second World War resulted in so much damage that Mattei’s final heir tried to give it to the municipality of Bologna, which refused the donation. In 1959, an entrepreneur bought it and, over the next two decades, tried and failed to turn it into a self-sustaining tourist attraction. Now, the Rocchetta is something like a museum (which contains, strangely but appropriately, a fascinating collection of mechanical music boxes and gramophones). Really, though, it’s a monument to the force of personality, to architectural self-fashioning – and to the era, long gone, when taking the cure at a pseudo-Moorish castle built by an eccentric Italian count seemed like a good idea.

From the December 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.