From the January 2016 issue of Apollo: subscribe here

‘I give the State all my works in marble, bronze and stone, together with my drawings and the collection of antiquities that I had such pleasure in assembling […] And I ask the state to keep all these collections in the Hôtel Biron, which will become the Musée Rodin, preserving the right to reside there for the rest of my life.’

In August 1919, only 10 years after Auguste Rodin had this document drafted by his lawyer – and just two years after his death – the Hôtel Biron opened its doors as the Musée Rodin. Few changes needed to be made, as it was already a museum of sorts. In the last years of his life the sculptor had used the elegant 18th-century property as a showroom and sculpture garden, as well as a studio; it was the public face of an essentially private man who retired every evening to the Villa des Brillants in suburban Meudon, home to his casting studios, his collection of antiquities, and his reclusive lifelong companion Rose Beuret.

For the Musée Rodin’s rehang, completed in November, over 100 antiquities and several plasters have been transferred from Meudon to the Hôtel Biron. In other ways the three-year refurbishment has been so sensitive that its former tenant would have no trouble recognising the place. True, he might be surprised to see the rotundas redecorated with the original 18th-century ornamental woodcarvings stripped out and sold by his predecessors as tenants, the Congregation of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, to pay for the chapel that now houses temporary exhibitions. He would almost certainly welcome the repainting of the whitewashed walls in a range of mid-toned greys pitched to set off white marble, plaster and bronze to equal effect, and be impressed by the colour temperature-controlled LED lighting system that tops up natural light falling through the windows. And he would appreciate the lift and cleverly concealed toilets, though perhaps not the modernist look of the new oak sculpture stands introduced to unify the displays.

Fans of the old museum may miss the more haphazard arrangement that permitted the illusion of personal discovery, though by Anglo-Saxon standards the new 18-room tour of 600 works is marvellously free of museographical interference. Arranged part-chronologically, part-thematically, the displays segue smoothly into one another. The first three ground-floor rooms trace Rodin’s beginnings as a sculptor, from an early portrait of his pinch-faced father Jean-Baptiste Rodin (1860) – the first sculpture he kept – to a terracotta bust of a Young Girl with Flowers on her Hat (1870), a vision as pretty as a Fragonard from his period in Belgium as an ornamental sculptor. It’s hard to imagine how the sweet terracotta Mother and Child (1866–70) could have given rise to the powerful plaster Study for John the Baptist (1878) in the same room. But the biggest surprises here are Rodin’s paintings – not the academic life-studies so much as the lively plein air landscapes painted in the Belgian countryside when he was still undecided between painting and sculpture. The way his brush carves form out of light and shade suggests that he made the right decision, while his lack of patience with painterly finish presages the ‘non finito’ urgency of his mature sculpture.

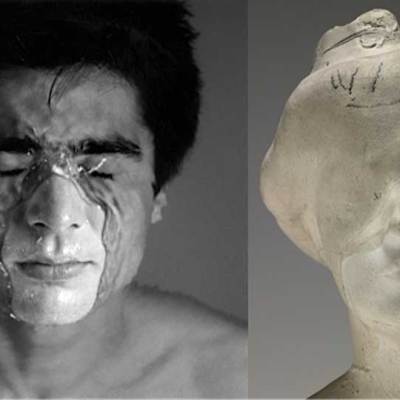

museoJM030 Installation view showing Rodin’s The Walking Man (1907) with pieces from the sculptor’s collection of antiquities Photo: Jerôme Manoukian

Rodin was not a great finisher, even of major works; he liked to keep the inspiration flowing. During the decade he spent working on The Gates of Hell (1880–c. 1890) – it wasn’t committed to bronze until after his death – the work became a fount of inspiration from which he drew more than 200 sculptures in the course of his life. He was a master of the spin-off. His public monuments – many unrealised during his lifetime after rejection by their commissioning bodies – were mined for standalone figures or groups, which acquire new meanings in isolation. As a tabletop bronze, The Damned Women (before 1890) from The Gates of Hell becomes a lesbian fantasy, while the swooping figure of Iris from the second, unrealised Monument to Victor Hugo (1891), stripped of her wings and head, becomes a classically fragmented and shamelessly erotic naked gymnast.

Rodin’s revolutionary use of changes of scale and fragmentation for recycling forms is explored in two adjoining first-floor rooms. The Large Head (before 1911) of Iris might have been broken off a Roman colossus, while a row of miniature plaster legs recalls a display of votive offerings. Rodin hoarded these spare parts, which he called ‘bozzetti’, for reconfiguring into different poses. By the 1900s he was experimenting with combinations of tiny plaster figures and found objects. ‘Antiquity is my youth,’ he said. It made him playful. Acrobatic nudes clamber, writhe or dive out of classical crocks, anticipating Surrealism by a couple of decades. In a rotunda hung with fragmentary heads, hands and feet, key pieces from his collection of antiquities revolve around his headless and armless The Walking Man (1907). He liked to keep such pieces around him for inspiration.

A narrow gallery has been set aside for works on paper – the newly acquired charcoal drawing for She Who Was the Helmet Maker’s Once-Beautiful Wife (1889) is the star of the opening display. An adjoining room shows works from Rodin’s collection of paintings by admired contemporaries such as Monet, Renoir, and Van Gogh, including the latter’s portrait of Père Tanguy (1887). A long-term friend, the Symbolist painter Eugène Carrière, gets a room to himself, where we see his vaporous style rub off on Rodin’s The Death of Adonis (1888) with its marble figures apparently blanketed in snow. The sculptor’s precocious pupil, muse, and tragic lover Camille Claudel merits another room, in which she shows herself a perfect chip off the master’s block – though not as surefooted when walking the tightrope between passion and kitsch.

Rodin was intensely relaxed about making money, whether from portrait busts or tabletop erotica, and he sensibly left his museum the artistic property rights to his works, enabling it to finance itself by casting bronzes from his original plasters. Since the 1970s the institution’s principal patron, the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Foundation, has donated over 450 works, including a number of these casts, to museums as a way of introducing the sculptor to new audiences. For closer acquaintance, the Hôtel Biron is the

place to go.