Five minutes into my second pose, the universe begins to melt away. I feel connected with the Life Room, telepathically in touch with the artists assembled to draw, paint and sculpt me. Earlier we had walked along the Cast Corridor, a vaulted avenue lined with copies of Greco-Roman sculptures that leads to this space, the spiritual heart of the Royal Academy Schools. Facing its two rows of raked benches and surrounded by statues of heroic figures from classical antiquity, I imagine all those who stood where I now stand, part of a centuries-old tradition. Where once my feelings of awe were moderated by disquiet – the hyper-idealised forms of nearby casts of the Farnese Hercules and Borghese Gladiator at odds with my own frame – a major refurbishment has since reinvigorated the room (now renamed the Dunard Fund Life Drawing Studio), complicating the ideals that previously defined it.

The formation of the Royal Academy in 1768, after King George III gave permission to ‘establish a school or academy of design for the use of students in the arts’, was the conclusion of a period of uncertainty for British artists working in the shadow of the Italian Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze and French Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. Led by its first keeper, George Michael Moser, and first president Joshua Reynolds, the RA Schools adopted the academic traditions of fine art according to which drawing from life was the summum bonum: the highest good. As such, each iteration of the Academy – from its original Pall Mall lodgings to its eventual home in Burlington House on Piccadilly – would incorporate a life room, within which the anatomical study of the nude model would take primacy.

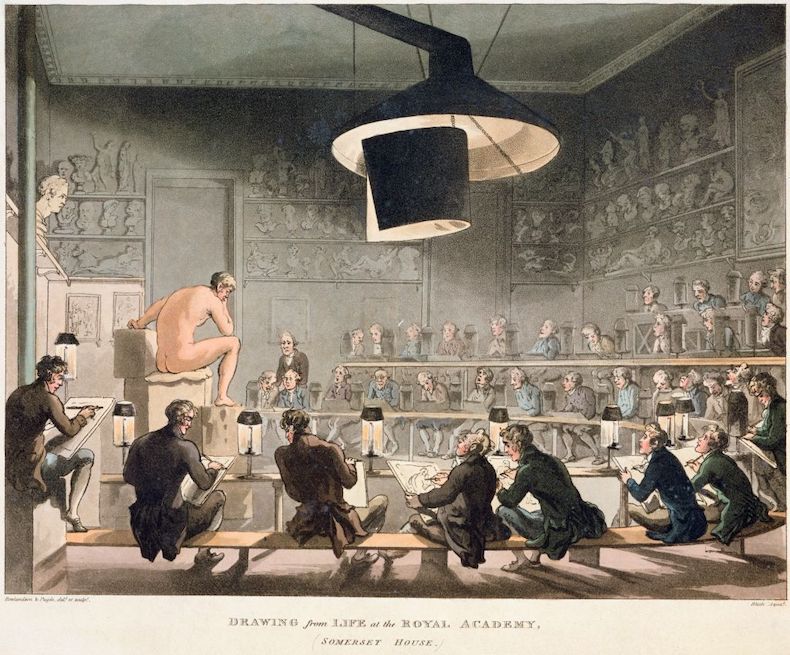

Drawing from Life at the Royal Academy, Somerset House (1808), Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin. Photo: Culture Club/Art Images via Getty Images

However, shifts in the art world, such as the development of the avant-garde (especially Impressionism) and later innovations such as performance art and conceptualism, eroded the authority of the academic traditions. Fewer students undertook life drawing, opting instead to incorporate new approaches into their work. After a period in which its relevance dwindled, in 1998, under new leadership, the RA Schools altered its focus entirely to become a school for contemporary art practice.

The Royal Academician and sculptor Cathie Pilkington first confronted the Academy’s conservative past in her 2017 exhibition ‘Life Room: Anatomy of A Doll’; the accompanying handout described the room as ‘a living relic of traditional art education’. Now, through her visionary re-curation – the most significant change since the mid-19th century – she has reimagined its artistic purpose, while a renovation by David Chipperfield Architects has refreshed the space. A new display of sculptures ‘presents itself as a Denkraum: a world of thought, a matrix of interconnections, a thinking space’, according to the artist. Through juxtaposing different time periods, mediums and narratives Pilkington has, for former keeper Eileen Cooper, ‘brought unpredictability into the room, which all artists know is the key to making art’.

The Dunard Fund Life Drawing Studio, formerly known as the Life Room, at the RA Schools in London. Photo: © David Parry

Where Herculean figures previously asserted dominion, they now jostle for attention with contemporary work. Current student Esther Gamsu’s unknown (couple) (2024), a pair of slumping latex heads, rests on the new ‘Students’ Shelf’ – a display that will change regularly – adjacent to Pilkington’s coquettish Reclining Doll (2013), which itself lies beneath Arthur George Walker’s maquette of Emily Pankhurst from 1930 (a notable placement given the historic exclusion of female students from the Life Room).

When I visited the Academy on the occasion of the Schools’ reopening in June, the Life Room had been transformed into a cinema showing audiovisual installations by current and former students, including Divine Southgate-Smith’s work Wakanda Forever (2021), a powerful critique of post-colonial attitudes that combines poetry with archival material. It felt as if the space had assumed a role more akin to a gallery at Tate Modern than to its previous use over two centuries, untethered to tradition. Reflecting on its changing use, Mark Hampson, the Academy’s long-serving head of Fine Art Processes, feels that ‘while life drawing is no longer an essential aspect of contemporary students’ [work], its historic legacy of discussions about identity highlights how the inspirations of the past inform the endeavours of artists emerging now’. Students now have greater scope for experimentation, a new platform to exhibit their work.

The display curated by artist Cathie Pilkington in the Dunard Fund Life Drawing Studio at the RA Schools. Photo: © David Parry

Given these developments, what future remains for the life model at the Academy? Life drawing and figurative painting have both experienced a resurgence in popularity in recent years, which is reflected in the many public courses still delivered in the Life Room. At the same time, modelling is itself coming to be recognised as an artistic practice in the realm of performance art. No longer engaged in a kind of anatomical data entry, choreographed contrapposto poses set by tutors have largely been replaced by improvised forms, while the classical conception of beauty once favoured by the Academy has been replaced by a greater diversity of models.

The Dunard Fund Life Drawing Studio is the oldest of its kind in the UK. The first time I arrived to model within it a decade ago, conscious that Blake, Turner, Constable and Reynolds had all sat at its benches, I was deeply moved. On either side of the easel, the space seemed charged with infinite creative potential, limited only by the imaginations of those artists who inhabited it. Following its renewal, I feel this now more than ever.