From the December issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

In the years since the Neues Museum reopened in 2009, the reconstruction job overseen by David Chipperfield Architects has become a reliable symbol for the continuing task of Vergangenheitsbewältigung – the coming to terms with the past that has been a keynote of post-war German culture. In the architectural firm’s own words, the reconstruction called for ‘a multidisciplinary interaction between repairing, conserving, restoring and recreating’. The original Neues Museum, designed by Friedrich August Stüler in the 1840s, had been severely damaged and in parts completely destroyed by Allied bombings in 1943–45; it was left to decay under the DDR. Only in 1997, post-unification, did reconstruction begin, and Chipperfield’s bold decision was to leave the ruins, bomb-holes and bullet-marks in place and rebuild around them. The building is simultaneously remnant and monument, a showcase for historical artefacts which itself embodies Europe’s disastrous history.

On the raw, drizzly afternoon when I last visited – implacable November weather! – Museum Island barely seemed to be above water level. The grand structures of the state museums, built on marshland in the middle of the Spree, were sunk in fog. Coming out from the S-Bahn and crossing the bridge, I found it hard to believe that so many visual artists could be drawn to a city with so little natural light for so much of the year. Yet the day was well suited to a trip to the Neues Museum. Filtered through this gauzy light, the present seemed already nostalgic, its outlines soft and instagrammatic.

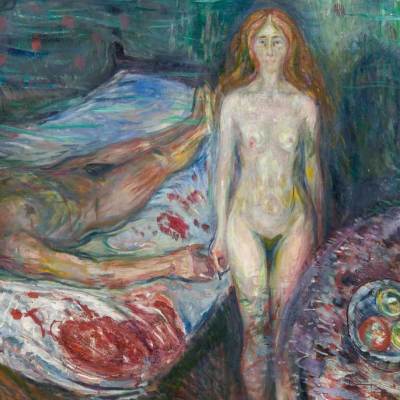

Currently nestled among the Neues Museum’s permanent holdings in the Ancient Egyptian galleries are 22 new oil paintings by Gleb Bas, an artist born in Kiev in 1980. The exhibition is called ‘Changing Identities’ (until 10 January 2016). Each painting takes a face from one of the Egyptian busts or statues and overlays it, using a variety of techniques, with the face of a living model to create a composite image. So, the head of a bust of Pharaoh Amasis II (570–526 BC) is layered into a contemporary woman’s face (a Japanese woman, going by the name) in a portrait called Amasis / Nahoko (2014). The effect is haunting, not least in the movement between the ancient, alien artefacts which exist in three dimensions and modern portraits in flat pictorial space that hang alongside them. The exhibition invites sentimentality – one can imagine how it might promote a bland, Family-of-Man mythology of continuities between past and present – yet Bas’s sensitive handling of paint somehow manages to stress the strangeness of both past and present, their difference.

The most famous treasure of the Neues Museum – and perhaps the most famous instance of how strikingly present artefacts from the deep past can seem – is the bust of Queen Nefertiti sculpted by Thutmose in 1345 BC, found at Amarna in Egypt in 1912 by the German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt. ‘Suddenly we had in our hands the most living Egyptian artwork,’ Borchardt wrote in his diary after the discovery. ‘You cannot describe it with words.’

When I interviewed the American painter Alex Katz in Paris last year, he told me that he considered Thutmose his ‘number one artist’ in history – ‘because he models as good as Raphael, and his line has got so much power and energy’. The Nefertiti in the Neues Museum does indeed look rather like one of Katz’s models – impossibly fine-featured, vividly beautiful and rich, painted in colours that come out at you fast and unforgettably. When Katz spoke in praise of Thutmose, the artist was telling me something I already knew about him, from interviews he had given over the previous 10 or 20 years. It was a story about his own relation to form, to modelling and line, which he had been telling people, and therefore telling himself, for a long time.

Nefertiti often seems to serve this sort of role for people. ‘The world’s most beautiful woman’, ‘Berlin’s most famous inhabitant’. One can’t use the transport system without seeing her face on posters for The Wyld, Berlin’s latest Las Vegas-style spectacular: ‘Every night she comes to life as the extraterrestrials’ queen […] But where did she come from and what has kept her young for 3,400 years?’

Like most of us, her reasons for being in Berlin don’t bear that much examination. Egypt would like to have her back. She almost did go back in the 1930s, until Hitler put a stop to it, dreaming of a new Egyptian museum in Berlin with Nefertiti enthroned at the centre of a huge dome. In today’s Neues Museum, Nefertiti stands alone in the North Dome Room on the building’s top floor. In Berlin one often feels history layered into itself in ways that are painful to contemplate. It seems right that the ruins and the reconstruction are hard to tell apart.