From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It’s rare that an exhibition introduces you to a bona fide modern master with whom you weren’t already familiar; rarer still when the corpus in question wipes any patina of cynicism from your critical outlook. But ‘Sam Gilliam: Sewing Fields’, at IMMA in Dublin, a display rammed with formal and intellectual inventiveness, is just such a show.

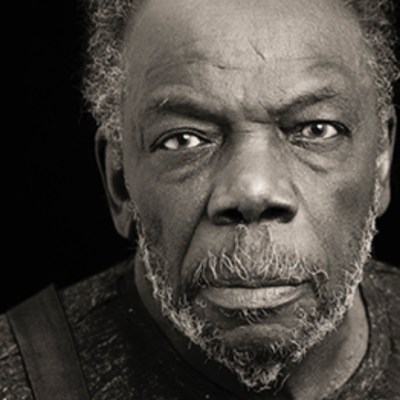

Gilliam (1933–2022) was born in the Depression-era American South and followed the Great Migration up to Kentucky, where he enrolled in art classes. After a move to Washington, D.C., he became associated with the city’s thriving Color Field painting scene, befriending the likes of Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland. From the late 1960s onwards, he radically reimagined what his chosen medium could be, splattering twisted sheet metal with expressive galaxies of colour, or stripping canvases from their stretchers to create assemblages resembling weather-beaten sails or battle standards. He blurred the boundaries between painting, sculpture and installation, turning the canvas itself into a dynamic compositional element that could be altered, in a way that was noisier and messier than any Fontana follower could have conceived.

The show concentrates on what has until now been considered a relatively minor aspect of Gilliam’s work, a series of paintings born of bureaucratic complications. In 1993, the artist was invited to take up a residency on the west coast of Ireland. To his horror, he discovered that no airline flying the DC–Shannon route would allow him to board with the petroleum-based paints that had become his calling card. So, with typically contingent flair, he improvised, pre-staining swatches of easily transportable canvas that he could carry on reshaping on foreign soil.

Gilliam, by his own account, hadn’t expected much from the residency, but the three weeks he spent in County Mayo opened a new dimension of possibility, one that he would pursue until his death in 2022. Working with local seamstresses using outdated Singers on a kitchen table, he turned the various scraps he had brought over into vivid painting-collages. So pleased was he with the results that, on returning, he would have sewing machines of the same sort shipped home to his studio.

There are four known works produced during his stay in Ireland, one of which we see here: Folded Cottages II (1993) is a jazzy collage of messy pleats topping out a narrow, vertical rectangle of synthetic fabric, the staining a kind of golden-hour camo-pattern that suggests a detail from a Turner sunset. Affixed directly to the wall, without support, it would be a remarkable piece on its own. But there is much better to come.

What follows feels like a riposte to Matisse’s cut-outs: Gilliam stitches and in one instance literally bolts ever less-likely formulations of fabric, paper, glossy inkjet prints, or whatever other materials come to hand, each component bearing tie-dye-like stains, raked hemispheres of impasto and even photos, some referring to previous works. The suture itself is worthy of inspection: some of the patterns, particularly in earlier pieces, conform to the configurations of the most basic of cheap sewing machines; others are more adventurous – wider, more obviously arrow-like, and in their repeated configuration, unmistakably directional, driving the viewer’s gaze around the composition like a toy car on a Scalextric course.

You can at times get the sense that what you’re looking at is in fact a display of avant-garde couture, so neat and deliberate are the nips and tucks in some of Gilliam’s frameless works: In Count on Us (2008), for instance, a sheet of synthetic muslin hangs directly on the wall from three supports, so as to resemble a trio of garments artfully cast from coat hooks; Curtains (1996) could easily have been a Leigh Bowery costume, had he ever attempted a performance of Joseph and his Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat. But this would be to ignore the intricate, almost topographic system of stitching in play.

As we see in a video from 1972 of the artist at work, Gilliam loved clothes, dressing stylishly even when he was working: he incorporated one of his outfits into a major painting, Composed (formerly Dark As I Am) (1968–74). A question hangs over the artist’s choice of materials: he would shop at army surplus stores or buy only the cheapest of synthetic fabrics; whether this came down to practice or symbolism we can only guess. Despite being active in the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s (and thence castigated by some on the Black left for making abstract rather than explicitly political, representational art), he understandably remained ambivalent towards such readings of his work. But a clue might lie in his use of gauzy, flimsy ‘tobacco fabric’, a cheap material sold to African-American wholesalers who could afford nothing better.

In Silhouette/Template (2) (1994), it is woven in between abstracted photographic prints. In Silhouettes/Templates I (1994), the fluffy material appears to billow from geometric patterns of different textiles resembling the compositions of Malevich or Goncharova – who, like Braque and Picasso, were key entries in Gilliam’s personal lexicon. Elsewhere, he plays with the associations of fabric itself, creating flag-like pictures-within-pictures: Silhouette on Template (1994) even carries what I take to be an allusion to the Irish tricolour.

This brings us to the premise of the show: that Ireland was an important influence on Gilliam’s late career. The argument might seem flimsy were it not for two points of evidence: first, that 30 years after his extremely brief visit, Gilliam was still giving his works Irish-specific titles; second, that he specifically requested some of his ashes to be cast from the cliffs at Downpatrick Head, near to where he had spent those productive weeks in 1993 – and after which he titled a good half-dozen paintings between 1994 and 2022. You make up your own mind; I know what I think.

‘Sam Gilliam: Sewing Fields’ is at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, until 25 January 2026.

From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.