‘Being here in person is very special,’ says Sarah Sze from Paris, just ahead of the opening of her new exhibition, ‘Night into Day’, at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art. She’s been in the French capital for ten days installing two new sculptures for the show: Twice Twilight, which uses a delicate scaffolding of metal rods and bamboo to suspend photographs, objects, light, sound and video projections on and around torn paper arranged in a spherical shape; and Tracing Fallen Sky, which features a pendulum that traces out the negative space above a mirrored, fragmented sculpture, reflecting slivers of images and objects. But ‘Night into Day is also much more than that, because Sze has used the entire structure of the Fondation Cartier to create it, projecting images and videos on to the walls and floors of the gallery and its facades to create ‘a light box of fleeting reflections and images’, blurring the boundaries between what is inside and outside, and also between what is image and reality.

Installing it in person almost didn’t happen because, with Covid peaking first in Paris then in New York, Sze’s home, and now returning in France, it seemed that she’d have to work remotely. Collaborating with a member of her team based in Paris, Sze had GoPro cameras set up throughout the building, designed by the celebrated architect Jean Nouvel, and worked on French time, getting up at 3am in New York. Only on 13 October was she finally able to travel. ‘It was very fascinating to see what you cannot do virtually and what you can,’ she says. ‘There are really important parts of the work that I never would have figured out [from New York] because they were very intuitive, spontaneous reactions to the space.

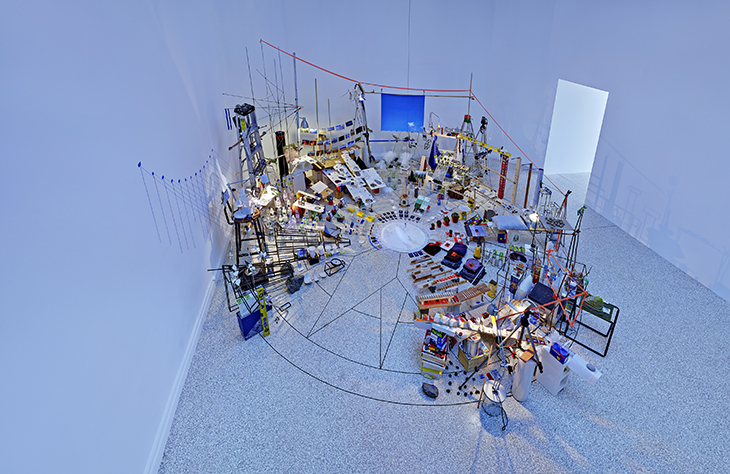

View of Twice Twilight by Sarah Sze in ‘Night into Day’ at the Fondation Cartier, Paris, October 2020. Photo: Édouard Caupeil; © Sarah Sze

And that’s strangely appropriate, because ‘Night into Day’ is the latest in an ongoing investigation into the relationship between images and information and our physical location in time and space, a series that considers ‘what does to us to have this amalgamation of the digital and the material’. Sze calls this series Timekeeper and traces it back to 2015, with an installation called Measuring Stick at New York’s Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, which included torn photographs, a fake rock sculpture, a video projection of a running cheetah, and a projection linked to NASA’s servers, counting out the ever-growing distance between Earth and the Voyager 1 space shuttle. It is an interesting evolution for an artist whose work initially considered our relationship with materials; the daughter of the Chinese-American architect Chia-Ming Sze, she trained in painting, and has included painting – or paint as a material or peeled off the walls – in her sculptures, along with everyday objects such as toothpicks, plants, and glasses of water. Her installation at the 2013 Venice Biennial, Triple Point, included objects such as leaves, and waterbus tickets, for example, gathered from the Italian city and added to the artwork over its three-month duration.

But the physical also features in ‘Night into Day’, albeit at one remove, because the videos shown in Twice Twilight centre on elements such as fire, air, water and earth, or on natural phenomena such as the setting sun, or the flickering of a flame. Other moving images she has included show hands transforming materials and were taken from online Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR) videos, which aim to stimulate a full body response to visual and auditory stimulation. It’s also weirdly apt now, as we go in and out of Covid-related lockdowns and (in most of the West at least) spend an increasing amount of time online, moving family gatherings, press interviews, and even exhibition installations on to Zoom.

Triple Point (Pendulum) (2013) Sarah Sze. © Sarah Sze

Sze describes Covid as a tragedy, but adds that it’s ‘a social experiment in isolation, and in what it’s like to have your main lifeline to the world through the screen’; though she’s been investigating this trend for the last seven years, it’s not something she wants to judge. ‘I don’t think it’s a polarisation – there’s too much talk of “Is it better or is it worse”,’ she says. ‘It’s just reality. We use it like we use a knife and fork these days, so then it’s a question of examining this language we’ve learned so quickly because we’ve had to, and become fluent in without really understanding what it is we’re becoming fluent in.’

It’s an intriguingly dispassionate stance, fitting for an artist whose works often evoke experiments or laboratories, or scientific techniques or equipment. The title Triple Point referred to triangulation, for example, the practice through which a unique position is specified by measuring from three points; it also referred to thermodynamics, and the point at which a particular combination of temperature and pressure means a substance can exist as a gas, solid, and liquid. ‘Night into Day’ and Triple Point both include pendulums, recalling clocks or maybe Foucault’s Pendulum and the Earth’s rotation in space; both also included spherical sculptures, references to planetariums. ‘As an artist, I think about the effort, desire, and continual longing we’ve had over the years to make meaning of the world around us through materials,’ Sze says. ‘And to try and locate a kind of wonder, but also a kind of futility that lies in that very fragile pursuit.’

‘Night into Day’ by Sarah Sze is at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art until 7 March 2021.