From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Urban explorers for whom the ruins of St Peter’s seminary at Cardross, the derelict Corbusian megastructure, are already old hat can travel 15 miles northeast to Drymen in Stirlingshire to discover one of the most intriguing sites of Victorian Britain. Buchanan Castle, designed as a castellated mansion for the Duke of Montrose in 1853, is today a roofless ruin overrun by trees on a thickly wooded site hemmed in on all sides by modern bungalows. The astonishing contrast between the castle’s gaunt, cleft walls – some still with patches of internal plasterwork clinging to them, looking as though they were growing up through Rumpelstiltskin’s forest – and the mid-century gentility of the little surrounding houses with their lawns and pink rhododendrons: here are all the elements of the uncanny that these explorers are looking for.

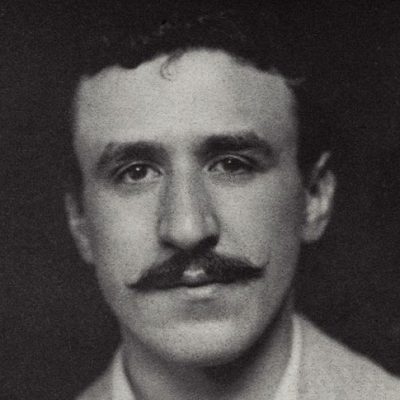

The castle, which was formerly known as Buchanan House, is most familiar to architectural historians for its complex plan; it’s that rather than its somewhat plain original appearance that takes up almost a whole page of Mark Girouard’s The Victorian Country House (1971). The design was the work of William Burn, the architect whose mansions for the aristocracy in both England and his native Scotland epitomise the sophisticated level of detailed planning that a mid Victorian household required: separate wings for the family and guests; separate staircases for male and female servants; separate domains for the housekeeper and butler; extensive kitchen offices providing a dedicated space for every activity; even a separate doorway and circulation route for luggage. Before Buchanan Castle was cracked open to the skies, it was crowned by tall conical roofs, sprouting from each corner; crowstep gables; a big tower on a square plan and several largish round ones; and rows of dormers that sprang from the tops of the walls in Scottish fashion, all of which compensated to some extent for the acres of masonry and the rows of bleak plate-glass sash windows below.

The east front of Buchanan Castle, Stirlingshire, designed in the early 1850s by William Burn (1789–1870). Photo: 1933. Photo: Heritage Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Buchanan Castle was thus a mature example of the Scottish or Scotch Baronial style. The spirit of the novelist Walter Scott, who was born 250 years ago, hovered over all these houses for decades. He had started planning Abbotsford, his own home, in 1812, intending from the outset that the fairly small building should exude warmth, hospitality, tradition and scholarship. He himself took control of the design, but from 1814 employed the architect William Atkinson as his amanuensis, and Atkinson had been one of those whose work mixed features to create a characteristically Scottish hybrid. There is a whole series of Regency-era gothic castles in Scotland – such as Atkinson’s Scone Palace and Tulliallan – that agreeably amalgamated early Georgian ideas with recent picturesque ones. Abbotsford has Baronial trimmings on its exterior but what Scott wanted, in his house as in his novels, was that stunning contrast between the sense of fortification on the outside and the warm, enveloping comfort – the ‘snugg accommodation’, as he put it – of dark gothic panelling within.

The arms room at Abbotsford, near Galashiels, designed 1812 by Walter Scott (1771–1832) with William Atkinson (1774/75–1839). Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The architectural historians Miles Glendinning and Aonghus MacKechnie, in their recent historical account, place the style not as an ugly Victorian aberration on the fringes of what Scott called ‘Caledonia, stern and wild’ but at the centre of a continuing story of how the architects of the country created a distinct national identity by repeatedly amalgamating elements of French and English architecture into Scotland’s vernacular across the centuries. Before Burn, classical architects such as William Playfair were designing castellated houses with elegant French renaissance touches, such as at Stonefield Castle near Tarbert in Argyllshire, but by the time the prolific Burn produced Buchanan Castle, many far less talented architects than him had already cottoned on to the fact that a plan that reflects the complexities of its functions is best expressed externally if turrets and niches can be freely added anywhere they are required. It may sound counterintuitive, but it is possible to see these houses as exhibiting a kind of Victorian functionalism. It was also an unusual style because it did not impose any particular kind of interior on its residents: these varied from room to room and house to house, sometimes more or less classical, sometimes rugged (and nowadays full of tartan and stags’ heads), and sometimes faintly gothic, if anything.

Balmoral Castle may look like this but in fact it is much less refined than a true Scotch Baronial residence. It has the big tower and the turrets, and the random interiors, but it is not planned with anything like the care of a Burn house. Even less was it designed with the panache and stylistic coherence of Burn’s partner and successor David Bryce, whose best houses combine a Burnian layout with subtle and balanced elevations. For the royal residence in their northern kingdom, Victoria and Albert chose J. & W. Smith, a low-key Aberdeen practice whose first recorded work had been a small prison in Fraserburgh, no doubt because the prince (like Scott nearly 40 years earlier) wanted the building designed by someone who would do exactly what he was told. It has a simple plan around a square courtyard of the kind that Burn or Bryce would have disdained.

Scotch Baronial had a reputation for cold and unwelcoming interiors. Writing in the late 1950s, Osbert Lancaster thought that ancestor worship blended with totemism explained these ‘vast, castellated barracks faithfully mimicking all the least attractive features of the English home at the most uncomfortable period of its development’. In George V’s day, Balmoral was indeed cold and tartan-drenched, and it bored Queen Mary, yet visitors found the atmosphere within convivial and even on occasion relaxed and fun.

Scotland is strewn with baronial ruins like those of Buchanan Castle; many more have been demolished. Some, like Kinloch Castle on the Isle of Rum, are still roofed and saveable, but there are others which need someone to make heroic efforts on their behalf. Balintore Castle near Kirriemuir, a Burn house of 1859, is currently being saved by its owner, David Johnston: these castles do still have their knights in shining armour.

From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.