Marking the centenary of the first group show of the quartet now known as the Scottish Colourists, this ambitious and provocative exhibition is the initiative of the Fleming Collection and has been organised by its curator emeritus, James Knox. It aims to set the work of these four Scots in a wider British and European context, supplementing the foundation’s own holdings with generous loans from the Tate and less well-known public and private collections. While arguing the case for positioning their art at the forefront of the avant-garde in Britain it also exposes the argument’s weaknesses.

This is a show of two halves. The first revolves around the two elder statemen, S.J. Peploe and J.D. Fergusson, friends in Edinburgh from around 1900 who were profoundly influenced not only by recent French art but also by an earlier generation of artists in Britain. Among these were John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler, both Americans who trained in Paris and made their homes in London, and the Irishman James Lavery, who studied in Glasgow and Paris before also settling in the south. The complexity of classifying their work according to national schools is evident from the first, and it continues as we encounter the brilliant expatriate Roderic O’Conor, friend of Gauguin in Pont-Aven and arguably more French than Irish in spirit; Augustus John and James Dickson Innes, who were born in Wales; and Anne Estelle Rice, a so-called Scotch-Irish American who spent nine years in Paris and her later life in London. It was meeting her in 1907 that prompted Fergusson to move to France, where he stayed until the outbreak of the First World War, and Fergusson, in turn, encouraged Peploe to join him, which he did from 1910 until 1912 and intermittently thereafter.

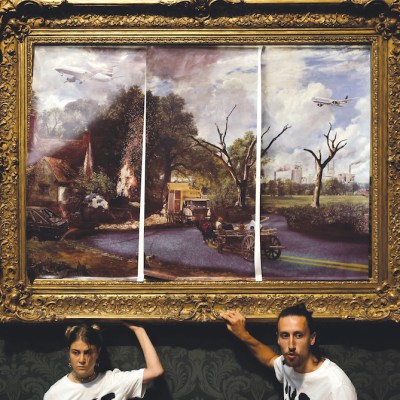

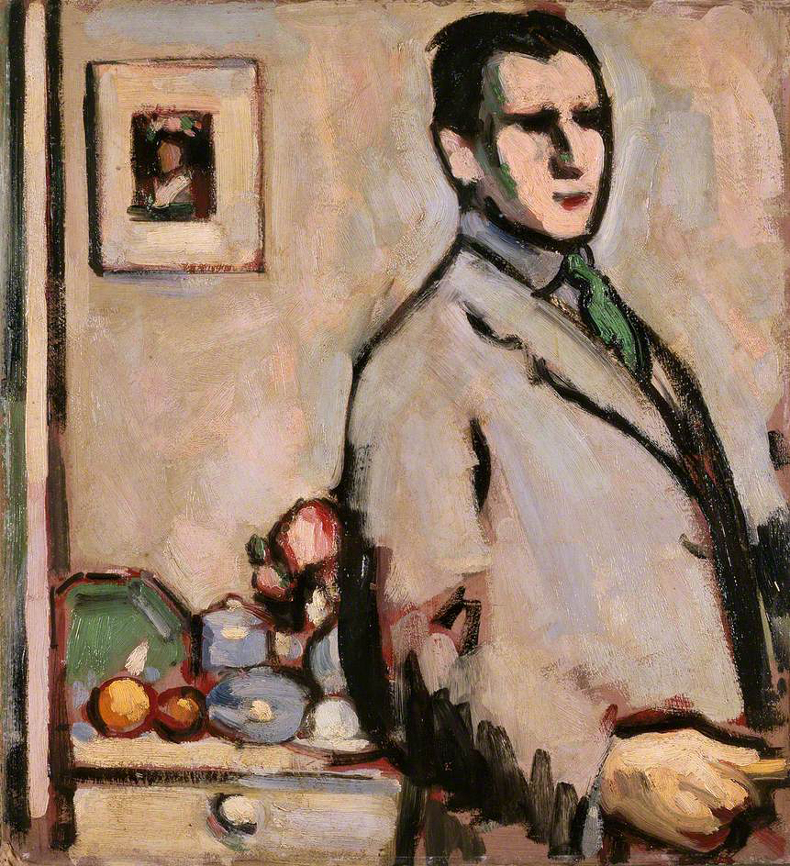

Self Portrait (1907), J.D. Fergusson. Photo: © Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries; courtesy Perth & Kinross Council

The show opens with Fergusson’s ‘swagger’ portrait of his first muse, Jean Maconochie, and the presence of Lavery and Whistler continues to be felt in the bravura brushwork and muted tonalism of Jonquils and Silver (1905) and Peploe’s Lady in a White Dress (1906), as do lessons absorbed from the study of Manet and Monet in the Musée du Luxembourg. It is not until the exhibition’s second gallery, however, that Fergusson and Peploe’s modernist credentials are made clear.

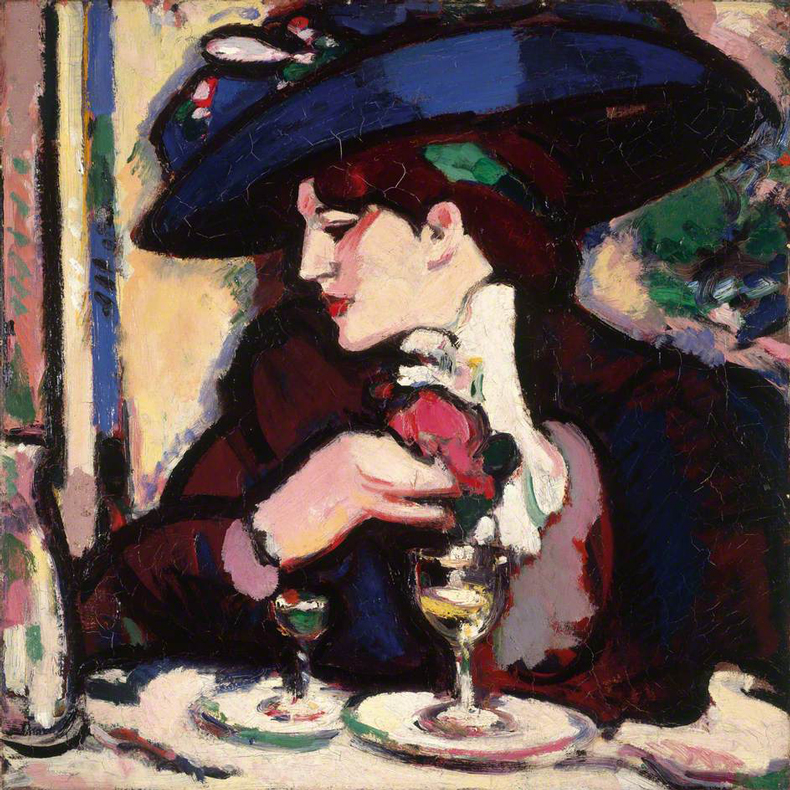

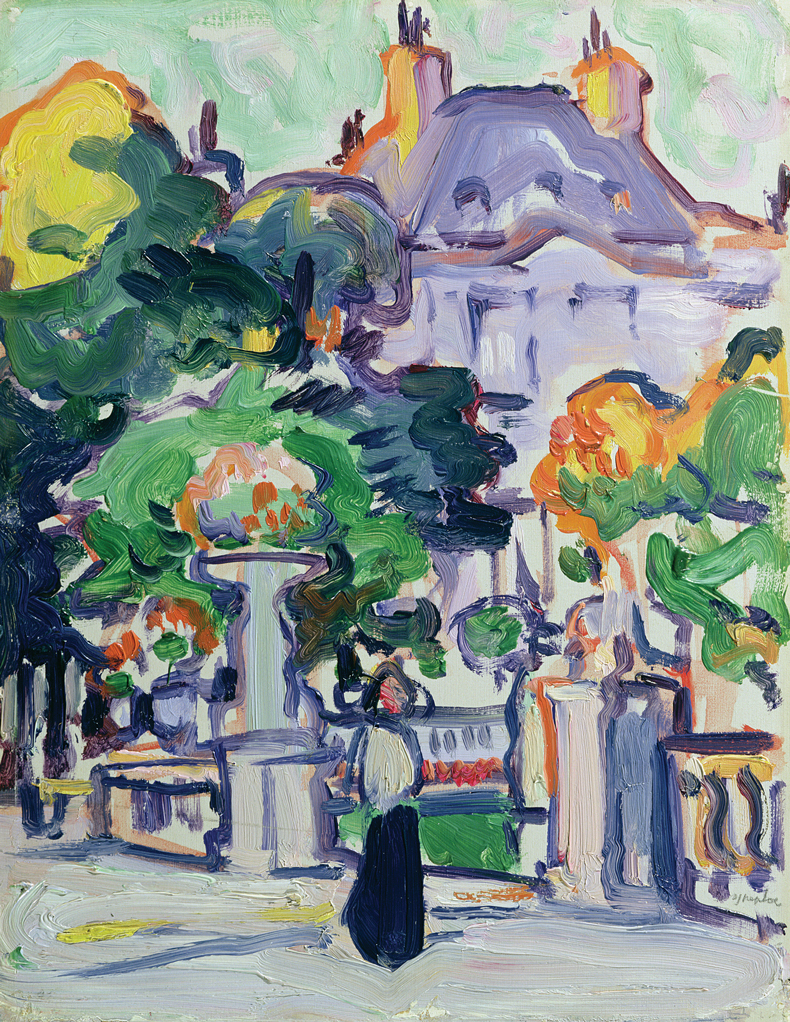

Fergusson’s Self Portrait of 1907 reveals a new graphic edge, and this flattening of form and summary handling is echoed in his cafe scene, The Blue Hat, Closerie des Lilas (1909). Featured here is the actress Yvonne de Kerstrat, who was to marry the American sculptor Jo Davidson – Fergusson and Rice’s great friend, and the sole member of their British-American circle to find considerable commercial success. Peploe’s oil study Luxembourg Gardens (c. 1910) is exuberant: in its use of non-naturalistic colour, variously coloured outlines and swift gestural brushwork leaving areas of the canvas almost negligently uncovered, it is a response to the radical approaches of Derain, Vlaminck and Matisse – artists dubbed ‘Les Fauves’ (wild beasts) by a critic of the 1905 Salon d’Automne. Matisse’s influence is more directly felt in Fergusson’s Blue Nude (1909–10) and in the decorative pattern-making of The Blue Lamp (1912).

The Blue Hat (1909), J.D. Fergusson. Photo: © Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries; courtesy Museums and Galleries Edinburgh/City of Edinburgh Council

These works flank the wall to the right. To the left hang canvases by their counterparts in London: Walter Sickert, Spencer Gore, Charles Ginner, Lucien Pissarro, Harold Gilman and Roger Fry. The contrast could hardly be more pronounced, not least with Sickert’s dark, muddy and heavily impastoed Mornington Crescent Nude (1907). The comparison neatly illustrates the critic C. Lewis Hind’s lament about Roger Fry’s Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in London in 1912, which had included a national component largely comprising Fry’s Bloomsbury coterie. ‘Why was this branch of British Post-Impressionism ignored by the directors of the Grafton Gallery – this branch that is so fresh and alive?’ he thundered. P.G. Konody echoed the sentiment, describing the English group as ‘dull and colourless’ by comparison.

These comments appeared in reviews of a parallel exhibition at the Stafford Gallery of artists associated with Rhythm magazine, a self-consciously modernist and international review of literature, art, music and theatre founded by John Middleton Murry and Michael Sadler in 1911, for which Fergusson acted as art editor and designed the cover. A profile of Anne Estelle Rice, ‘Fauvism and a Fauve’, launched its art criticism, and its first issue included a graphic version of Peploe’s Luxembourg Gardens and an illustration by Picasso, plus experimental nudes by Rice, Jessica Dismorr and the American Marguerite Thompson (later Zorach) – all artists based in Paris. Later issues included the work of another expatriate Scot, variously known as Dot, George or Georges Banks, a caricaturist with a mordant wit. Some of Fergusson’s own issues of Rhythm are displayed here, as is Dismorr’s Fauvist Landscape with Figures (1911–12), a rare surviving work by an exceptional talent.

Luxembourg Gardens (c. 1910), S.J. Peploe. Courtesy the Fleming Collection

Hind’s rhetorical question may be simply answered by the fact that Roger Fry did not care for Fauvism or the group known as the Rhythmists. Even Fry’s friend Sickert summed up the division as ‘Post-Impressionists licensed by Mr. Fry, and those unlicensed by Mr. Fry’. Fry’s control over the narrative of modern art in London, and his aversion to intense colour and heightened emotion, proved prejudicial to the reception of these artists south of the border.

The Rhythmists had far more in common with O’Conor and Dickson Innes. The latter’s work had been transformed by the light and colour of the Mediterranean South after his visit to Collioure in 1908, and his Arenig, North Wales (1913) is one of the revelations here, the peaks of the rose-tinted mountain infused with a symbolism also apparent in Rice’s Mediterranean landscapes, such as Côte d’Azur (c. 1914). Innes died of tuberculosis the following year – one of several represented artists unable to realise their promise fully, the ‘Glasgow Girl’ Bessie MacNicol (1869–1904) and Robert Brough (1872–1905) among them.

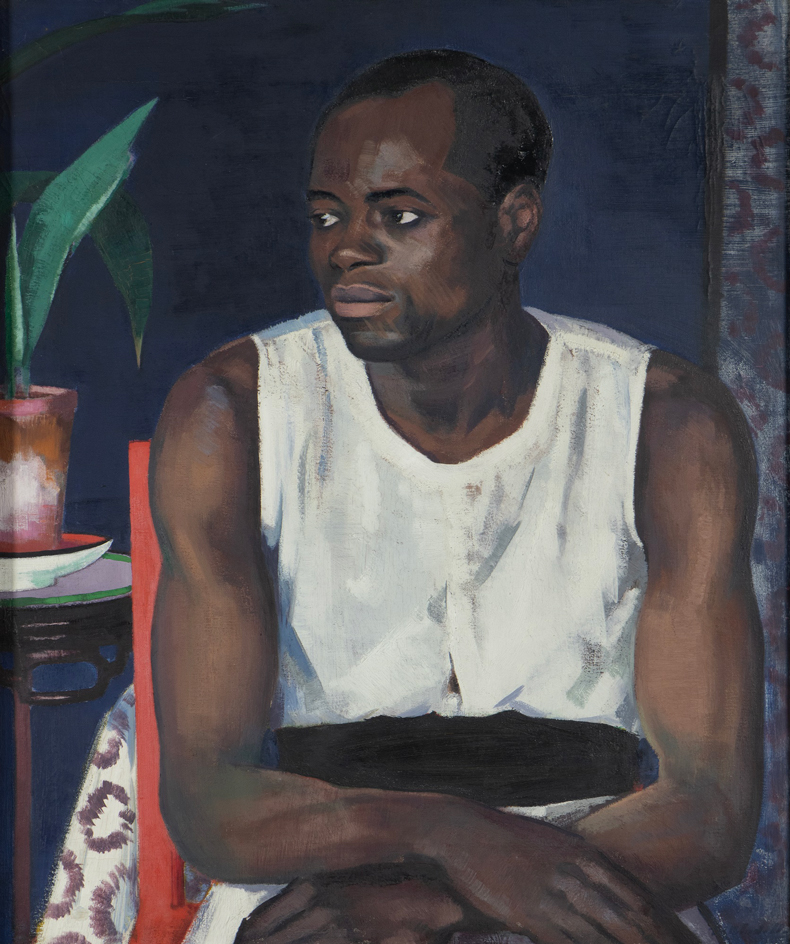

The White Shirt (c. 1922), F.C.B. Cadell. Courtesy Dundee Art Galleries and Museums (The McManus)

Arenig is happily situated between The Blue Pool (1911) by Innes’s close friend Augustus John and Derain’s Thames view The Pool of London (1906). The latter’s rough, almost childlike application of bold complementary pigments inadvertently serves to emphasise how tardy and tentative the British Fauves were in their response to the radical art of their French counterparts. The notion of the radicalism of the Scottish Colourists is stretched further with the introduction of the quartet’s two later leading lights in the second half of the exhibition, F.C.B. Cadell and Leslie Hunter.

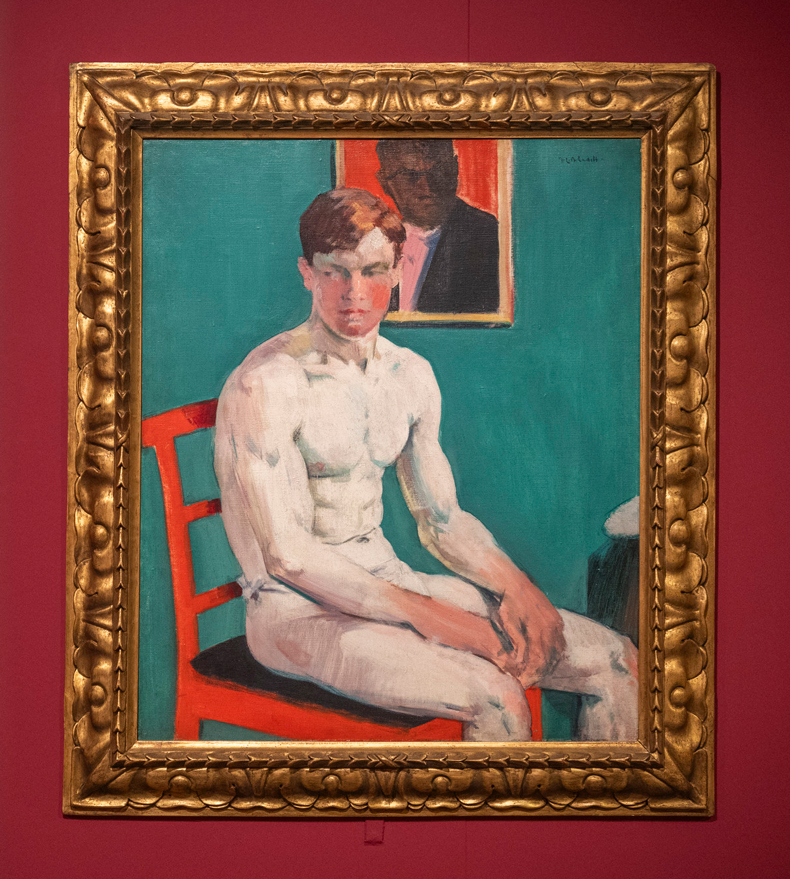

There is no mistaking the facility and delectable results of Cadell’s The Feathered Hat (c. 1914) and studio still life Carnations (1913), but these are Whistlerian exercises a half-century after the event, and a good decade on from Peploe and Fergusson’s meditations on Manet. There is no mistaking his competence as a colourist or modernist, however, in the geometry and brilliant teal and scarlet of his nude portrait of the boxer William ‘Basher Willie’ Thomson of around 1925, the sitter’s chalk-white skin contrasting with one of the artist’s many portraits of Black sitters hanging on the wall behind. Another, thought to represent Jack Abrew, a merchant seaman from Cape Verde who settled in Leith, hangs alongside. Arguably, the best of the paintings by Hunter is The Canopy (1914), but this image of gaily striped beach tents has little of the boldness of similar subjects by Albert Marquet and Raoul Dufy of c. 1906, or by Fergusson and Rice painting in Royan in 1910. While Peploe’s continued brilliance as a colourist and quest for the perfect still life is evident in his meticulously arranged compositions of the 1920s, this work, however indebted to the proto-Cubism of Cézanne, has become essentially academic.

Installation view of The Boxer (1925) by F.C.B. Cadell at Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh

The abrasive counterpoint between north and south does soften, with the First World War proving a turning point as artists across Europe returned to classical order and tradition. For Peploe and Cadell, this retreat resulted in subtle, luminous landscapes of the unspoilt Hebridean island of Iona; Fergusson, meanwhile, created a gleaming pagan bronze head, Eástra (Hymn to the Sun) (1924). This is an illuminating show, and it leaves us with much to digest.

Susan Moore is writing a book about Anne Estelle Rice, which will be published in 2027.

‘The Scottish Colourists: Radical Perspectives’ is at Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh, until 28 June.