On Easter Sunday, 9 April, the Side Gallery in Newcastle closed for a projected 18 months – and perhaps for good, a prospect that its remaining staff have reason to fear may happen, even as they work towards securing the gallery’s future. The announcement came just days after a much-lauded retrospective of the late Chris Killip (director of Side from 1977–79), opened across the River Tyne at Baltic, after a successful run at The Photographer’s Gallery in London. The incongruous timing points to tensions about where and how social documentary photography is valued: in art centres and in the art market, where signed prints can fetch five-figure sums, or in the post-industrial regions whose hollowing out these images have depicted in haunting and humane detail.

The Side Gallery was founded in 1977 as a free venue for documentary photography and film screenings in the heart of a city that had thrived thanks to shipbuilding and coal-mining. The gallery quickly established a reputation for bringing high-calibre photography exhibitions to the region. In 1978, it curated a 70th-birthday retrospective for Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Side has hosted other famous names over the years, including Weegee, Robert Doisneau, Diane Arbus and Sebastião Salgado.

However, the Side Gallery is most closely linked with the work of its founder-owners, the Amber film and photography collective. Set up in London in 1968, where co-founder Martin Murray had been studying at Regent Street Polytechnic (now the University of Westminster), Amber moved to Newcastle in 1969, attracted by funding from Northern Arts, low overheads and the artistic aim of exploring working-class life from within. It rented studios in the then-dilapidated Quayside, later buying up the space that Side – named for its street address – still occupies, for now.

Their experience of higher education had left members of Amber feeling estranged from their roots and highlighted the absence of positive representations of working-class life. Amber aimed not only to operate as a collective (members pooled their incomes and shared all decisions), but also to work in collaboration with communities such as the Byker neighbourhood, where co-founder Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen, from Finland, chose to live and work. Although her photographs are now in major collections such as the Tate and the NGA in Washington, D.C., the project was unusual at the time: an intimate, clear-eyed portrait of life going on as best it could while the entire district was demolished for a motorway and social housing development. In a BBC television interview with Konttinen in 1974, a condescending male journalist challenged as ‘strange’ her description of its hillside Victorian terraces, and impoverished residents, as gentle. ‘It’s strange only to people who have strong prejudices about Byker,’ she replied.

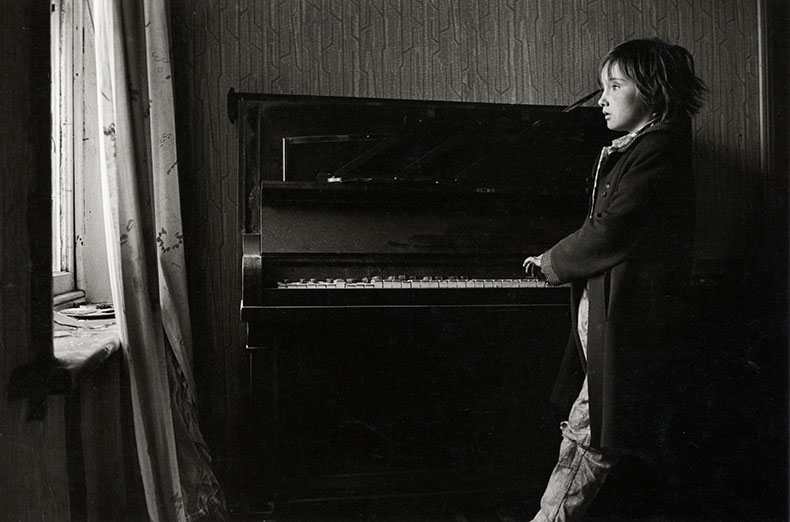

Heather playing the piano in a derelict house (1971), Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen. AmberSide Collection; © Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen

The Byker film and photobook of 1983 exemplified Amber’s immersive approach and aesthetic sensibilities, encouraging the group to undertake other long-term, place-based projects at a time of ever-faster deindustrialisation under the Thatcher government. Its work documented the life of local factories, the demise of shipbuilding at Wallsend, the 1984-85 miner’s strike and evocative seascapes where nature met the ravages of heavy industry and people scraped livings by fishing or gathering waste coal from the sea. The Side Gallery exhibited work by Amber members, including Graham Smith, Isabella Jedrzejczyk and Mik Critchlow (who passed away in March), as well as up-and-coming British and international photographers. Nick Hedges, Daniel Meadows, Tish Murtha and Dayanita Singh all featured in Side projects early in their careers. The gallery also formed a collection of documentary photography ranging from Martin Chambi’s Indigenismo–movement images of 20th-century Peru to Mary Gillens’ personal glimpses of Wheatley Hill, the County Durham mining village where she lived in the 1920s.

In 2014, a major grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund allowed the Side Gallery to extend and upgrade its gallery, cinema and archive spaces, create a shop, and digitise its collections, while funding from the Paul Hamlyn Foundation supported its programmes with local schools and youth. From 2018, it secured Arts Council England National Portfolio Organization (NPO) status, with a one-year Covid-19 extension that saw it through 2022. But in November, the Arts Council did not renew the gallery’s NPO status, a loss of £120,000 a year. Before announcing the closure last week, Side awaited the outcome – fortunately successful – of a transitional funding bid to the Council, allowing it to meet its short-term commitments and wind down its gallery operations. The collections are protected by the Amberside Trust.

Seafarers. Somali Deck hand – SS Drupa (1980–89), Mik Critchlow. AmberSide Collection; © Mik Critchlow

The Arts Council has given no reason for the withdrawal of Side’s NPO status, but a general trend has seen its funding flow from city centres to small towns and rural areas. Of the £446 million the Council distributed for 2023–26, more than 85 per cent (£383 million) went to the North, reflecting the Conservative government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda. In real terms, the figure represents a cut compared to the £407 million available for 2018–21, even as the utility bills of organisations like Side have skyrocketed.

Transition funds cannot be used to develop new activities or bids, hence Side’s difficult decision to launch a crowdfunding appeal. The outpouring of affection and donations speaks to the Side Gallery’s renown as a photography and film venue and the effect it has had on visitors who may never have found themselves in a gallery before. Unique, invaluable, inspirational, transformative, a beacon of light, or simply ‘we love you’, are among the words donors have used to describe what Side means to them as well as to the city and region. But a regional focus does not mean that either the Side Gallery or the Amber Collective is parochial. Their work speaks to larger and global themes. The Side’s latest (one hopes not last) exhibition was ‘A wounded landscape’, the UK premiere of Marc Wilson’s six-year photographic journey across sites associated with the Holocaust. The gallery’s curatorial choices have often reflected contemporary events and anxieties, in this case the rise of far-right political parties.

The gallery’s curator, Kerry Lowes, first visited the space as a teenager from East Durham, where mining communities had been devastated in the 1980s. ‘There is nothing like Side,’ she says. Its free admission, welcoming atmosphere, social conscience and commitment to the documentary genre reflect its founding principles and its ongoing resolve to inspire greater tolerance and empathy in the world. If photography lets visitors stand in someone else’s shoes for a moment, as Lowes puts it, then for 46 years, the Side Gallery has ensured those shoes most often belong to the underrepresented, the misrepresented, and the overlooked. Judging by reaction to its news and the crowdfunding campaign, supporters of Side share the Amber Collective’s original conviction, namely that documentary photography can shape a more just society, even as the gallery’s own future is at stake.

#Saveside, the crowdfunding campaign of the Side Gallery in Newcastle, is here.

Christina Riggs is the author of Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century (Atlantic) and a professor of visual culture at Durham University, where she teaches photographic history – including the work of the Amber Collective.