On 6 July 2016, Philando Castile, a black school cafeteria worker, was shot and killed by a police officer during a traffic stop in Minnesota. Sitting in the passenger seat, his girlfriend Diamond Reynolds broadcast the immediate aftermath of the shooting on Facebook Live. In a video that has since been shared over 6 million times, we witness a tragedy unfold as Reynolds repeats over and over the sequence of events that led to the shooting; Castile slumps unmoving next to her, before the screen goes black.

In the months following the shooting, artist Luke Willis Thompson began a dialogue with Reynolds. Researching the history of the London race riots in 1981 and 2011, Thompson had become interested in the growing number of videos of police violence circulating online and the changing terms of visibility this amateur cellphone reportage enabled. He proposed to produce a work that could act as a ‘sister-image’, that did not seek to counter the original, but to present a different moment, beyond the widely shared footage of Reynolds embedded within the unfolding news. The result is autoportrait, a complex and powerful 35mm black and white film currently on show at Chisenhale Gallery in east London.

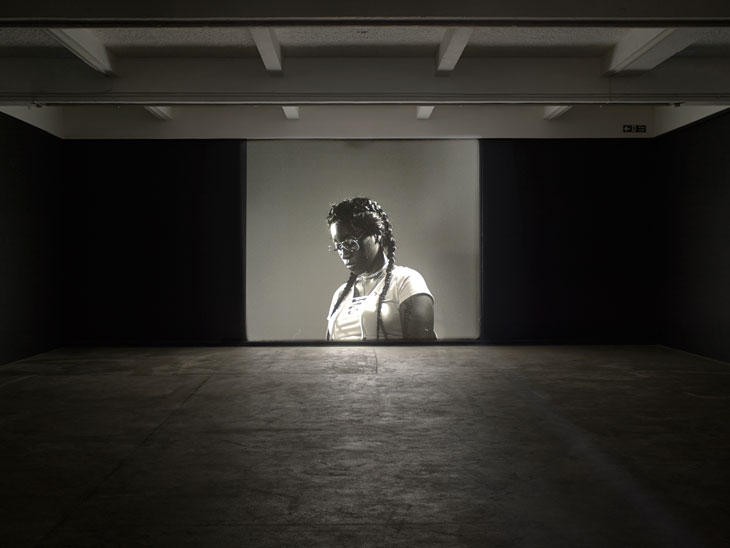

autoportrait (2017), Luke Willis Thompson. Installation view at Chisenhale Gallery 2017. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate

The film presents a portrait of Reynolds in two parts, shown as a vast single screen work in the dark space of the gallery. The first is shot from close range; we see her face in high definition, her eyes looking defiantly towards the viewer from under heavy lashes. Intensely lit, her expression is half obscured by shadows, lending an air of golden-age Hollywood glamour. She sways slowly, almost imperceptibly, as she silently mouths something we cannot understand. The second, shot from further away, brings her shoulders and torso into the frame. She is near motionless, glancing up occasionally to a point off camera before casting her eyes at the floor once more. The video repeats without pause, jumping from one to the other against the mechanical whirring of the projector echoing through the empty space.

Thompson’s portrait of Reynolds gives agency to its subject, allowing her to reclaim her own representation from its endless circulation in and appropriation by the media. Contrasting the fast-paced violence of the live video, it offers instead a moment of stillness and reflection in which a single shot is drawn out over several minutes. Thompson’s use of film is important here; the lengths of the two parts are each defined by the length of a roll of film. Unedited, and able to be viewed only in a controlled environment, the film has not been manipulated beyond its original intentions. Through this, Reynolds lays claim to her own image.

autoportrait (2017), Luke Willis Thompson. Installation view at Chisenhale Gallery 2017. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate

Viewed against the backdrop of recent controversy surrounding the representation of black trauma at this year’s Whitney Biennial, autoportrait’s contribution is crucial. Well documented at the time, Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black boy murdered by a white mob in 1955, led to protests in which Schutz was accused of reenacting the violence of the original image through its appropriation. The Biennial included a vivid painting of Philando Castile by Henry Taylor, in which a faceless body holds a gun over Castile’s lifeless figure. Unlike Schutz, Taylor is a black artist. When protesters stood in front of Schutz’s painting with t-shirts that read ‘Black Death Spectacle’, a renewed urgency around the stakes of representation came powerfully to the fore.

As in these two paintings, autoportrait does not give a voice to its subject. Reynolds’ silence reminds us of the continuing effect that day has on her reality. During the discussion and production of the piece, Reynolds was a key witness in the prosecution against the police officer and was instructed by her lawyer not to speak on film. In the days before the exhibition opened, the officer was acquitted of all charges. Her silence becomes something else entirely: the silencing of black voices against a continuing injustice. In a week that has seen riots in east London over the death of a young black man who was apprehended by police, the endless loop of autoportrait captures something of the interminability of the current moment, situated outside of its original context, yet drawing comparisons that are all too clear.

Luke Willis Thompson’s autoportrait is at Chisenhale Gallery, London, until 27 August 2017.