From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In July 2022, the San Francisco-based company OpenAI posted to its blog an array of headshots made by DALL-E 2, an artificial intelligence app. From a simple phrase – ‘a portrait of a woman’, ‘a portrait of a heroic firefighter’, or ‘a photo of a CEO’ – DALL-E 2 uses AI to generate several novel and impressively convincing images to match, each a plausible likeness of a woman, a firefighter, or a CEO.

Other text-to-images AI apps, such as Stable Diffusion and Midjourney, have been similarly trained to produce credible new human faces. Close scrutiny reveals a few tells: the eyes and teeth aren’t quite right, the fashions are impossible to date. But the resemblance to people is so strong, the trick of producing unique pictures so compelling, that it is easy to overlook the mismatch with the first word in the phrases used to generate them. These are not portraits of women or firefighters, which would assume they represent real people, or photos of CEOs, which would rely on the recording of variations in light intensity. Instead, they simulate a representational genre, the portrait photo. In doing so, they give AI a face (or many) and position this latest technological advance firmly within the visual culture of Silicon Valley, the region of California most associated with the high-tech industry.

AI-generated portraits belong to a well-established tradition of using portraiture to represent machines and of creating portraits with those new machines. Pictures (mostly photos) of inventors, engineers and company founders have long mediated our relationship with the engineering marvels produced in Silicon Valley. Today’s tech companies are often associated with a famous face: Elon Musk and Tesla, Mark Zuckerberg and Meta, Steve Jobs and Apple. But whatever the era, whatever the latest technological advance – vacuum tubes, semiconductors, personal computers or neural networks – portraits have promised a way to grasp innovations that are too small, too complex or too visually opaque to stand alone. In turn, a machine’s ability to craft a portrait – or to manipulate those crafted by humans – seems to testify to increasingly sophisticated technological capabilities.

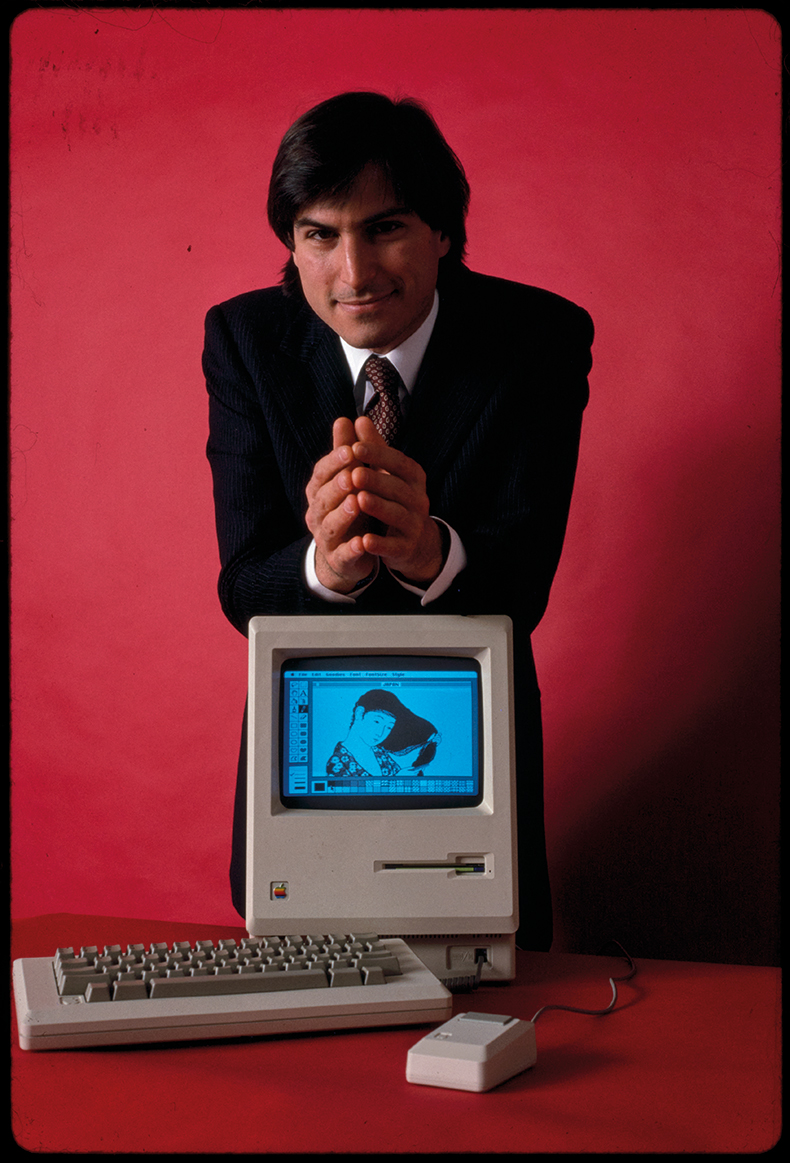

Steve Jobs photographed with the Apple Macintosh in 1984 by Bernard Gotfryd (1924–2016). Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

The reliance on portraiture is evident even in the era before silicon chips would give the area its nickname. In 1953, Fortune magazine hired Ansel Adams to photograph Russell and Sigurd Varian, two brothers who were early contributors to the region’s burgeoning electronics industry. But Adams struggled with the assignment. Although best known for his landscape photographs, he was a capable portrait photographer; it wasn’t the human subjects that stymied him as much as how to depict them alongside the specialised vacuum tube that they had invented several years earlier. A klystron (as the device was called, after the Greek for ‘to play in waves’) amplified microwaves, and it was first used for military aviation radar systems, allowing pilots to navi- gate under adverse conditions, and later for commercial applications such as increasing the strength of television broadcast signals.

In an effort to show both the people and the technology in the portrait, Adams settled on a somewhat awkward composition that calls attention to the scale of the klystron. The large, visually unremarkable copper-coloured tube, which looks something like a giant spark plug, nearly fills the left side of the photo. The two brothers stand on the right side; Sigurd perched on an unseen ladder with Russell immediately below him, only his head and shoulders inside the frame. Together their height equals that of the klystron. But nothing about the photo conveys how the klystron functions or any possible applications. Dissatisfied, Adams wrote to an editor at the magazine, ‘The tube is more impressive in its implications than in actual appearance.’

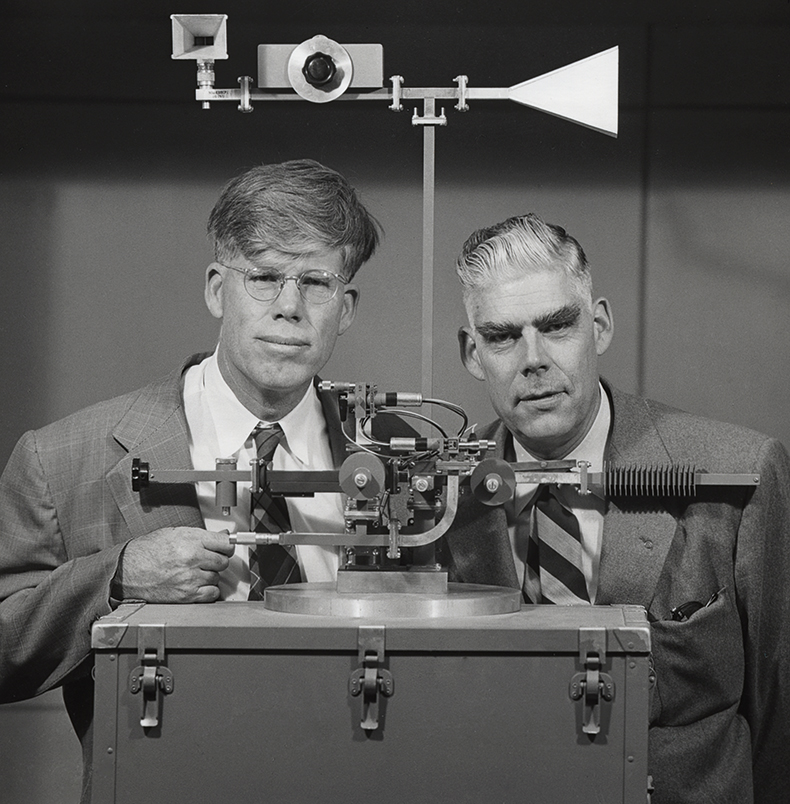

Less than a year later, Adams took another portrait of the Varians, this time for a feature in LIFE magazine titled ‘The Face of Revolutionary Technology: Wizards of the Coming Wonders’, which declared that ‘[t]he mark of genius and the hope of the future is on the faces of these pensive and little-known men, surrounded here by the Rube Goldberg gadgets of their profession’. Once again, the brothers and a device share the frame, but the longer one looks, the more the human subjects fade into the background and the apparatus draws attention. Instead of a dull copper tube, the Varians sit behind a contraption rich in visual interest: bars and cables bend in opposing directions, discs and fasteners of varying sizes and textures adorn it. A staff and crossbar rise behind them, one end flaring out like a weathervane and the other holding a megaphone and a knob and disc arranged to suggest a camera lens.

As they stare straight at the photographer, the brothers’ expressions are difficult to read. But perhaps Sigurd’s face (on the right) shows a hint of a smirk? In his autobiography, Adams gleefully confesses that this machine had no functionality. He and the Varians had assembled it from spare parts in their laboratory. Adams offers no explanation for the choice. A practical joke? A replacement of the unphotogenic klyston with something more visually appealing? Or maybe the resemblance to weathervanes, megaphones and a camera lens – all tools that amplify or magnify in some manner – suggests the applications of the klystron. As a likeness, the photo fails, quite intentionally, to represent the technology. But much like a portrait of a sitter surrounded by objects that represent the interests and pursuits that define them, it conveys something of what defines the klystron.

Within a few short years, showing humans alongside the technology became impossible as semiconductors on silicon chips the size of thumbnails took over the electronics industry. By focusing on people, the group portrait Wayne Miller took in 1960 of the founders of Fairchild Semiconductor, the company that introduced silicon chips to the market, returns the technology to a more manageable scale. The photo emphasises the commonality of the eight men (Gordon Moore, C. Sheldon Roberts, Eugene Kleiner, Robert Noyce, Victor Grinich, Julius Blank, Jean Hoerni and Jay Last). They wear nearly identical dark suits with white shirts and sport similar haircuts and eyeglasses. Men like these, as well as the mid-century modern decor of their office (marked by a different logo, but still in gleaming chrome), might be found in many a place of business across the United States.

At first glance, it’s hard to reconcile the uniformity of the men with the nickname they bore: the Traitorous Eight. All had been carefully vetted and hired by William Shockley, the Nobel prize-winning co-inventor of the transistor, to work for his semiconductor company but, frustrated by Shockley’s controlling management style, they quit and started their own. Again, close study of the portrait offers insights into how to understand the technology and its impact. Miller carefully arranged the men, an approach that contrasts with his more typical shoot from-the-hip photographic style. Each holds a different seated pose within a shallow space and gazes confidently back at the viewer. It’s a composition that recalls 17th-century portraits of Dutch regents by Rembrandt or Frans Hals, an earlier era’s celebration of its ruling class. Miller’s choice lionises the men in the portrait and predicts the significance of Fairchild Semiconductor. Over the next decade, all would strike out on their own, founding multiple companies and spin-offs: semiconductor manufacturers, venture capital firms and computer micro-processor companies. Miller’s portrait asserts their importance and suggests that these men would be the regents of Silicon Valley, shaping the technological future.

That future would eventually deliver the technological innovations of Silicon Valley into the hands of the consumer. The Apple Macintosh, introduced in 1984 with an innovative graphic user interface and mouse, made the personal computer friendly, easy to use and intuitive. Portraits that promoted its arrival once again brought together human and machine as in photojournalist Bernard Gotfryd’s shot of a smiling Steve Jobs leaning on a Macintosh. Jobs’s foreshortened hands, fingertips pressed lightly together, call attention to the way the mouse enables control of the computer with a few hand gestures.

Interestingly, the portrait of Jobs and a Macintosh incorporates another portrait, that of a kimono-clad Japanese woman on the glowing computer screen. Unlike Jobs or the men in the earlier portraits, she turns her face slightly away and her eyes look downward as she meditatively combs her long, black hair. It’s a private – even intimate – scene, giving new meaning to the phrase ‘personal computer’. The portrait appeared frequently on Macintosh screens in advertisements and promotional materials from the period, as well as on the cover of the manual for MacPaint, the innovative graphics program that came bundled with the computer.

The quiet, contemplative mood of the image on the computer contrasts with the extroverted personality of the Macintosh, which famously said ‘hello’ in ads and demos. The subject’s identity – an Asian woman – contrasts with the dominance of white men in representations of Silicon Valley. But the anonymous, anomalous figure announces a shift. Instead of a portrait of technology or of technology’s creators, she signals that Silicon Valley’s technology can now make portraits. As a Macintosh advertisement of 1984 promised: ‘With MacPaint, for the first time, a personal computer can produce virtually any image the human hand can create. Because the mouse allows the human hand to create it.’

The portrait of the Japanese woman alsorequired some inventive sleight of hand. Members of the Macintosh development team were simultaneously creating the computer and exploring its capabilities, including experimenting with image scanning. Among the images they tested was a Japanese woodblock from 1920 by Hashiguchi Goyo, a copy of which Steve Jobs is said to have owned. Once the image was available in digital form, Susan Kare, who designed the icons, fonts and other components of the Macintosh interface, used MacPaint to modify it. The resulting image is both copy and original, a collaboration between multiple humans and machines.

Some examples of what OpenAi’s artificial intelligence app DALL-E 2 thinks a CEO looks like

In the 21st century with the rise of social media, Silicon Valley doubled down on the value of portraiture and introduced new methods to create multifaceted, personalised profiles. Facebook, which took its name from a directory of photos of Harvard students, allowed each user to craft a self-portrait by posting curated images and information and changing them at will. The company, rebranded as Meta, carries that promise of self-fashioning to a new platform, now through designing avatars for virtual spaces. But the users’ control over their own images may well be illusive. Regardless of what a profile picture might show, the data portraits constructed and compiled through users’ actions and connections are much more revealing (and financially valuable) to contemporary technology companies.

As the latest example of Silicon Valley portraiture, AI-generated portraits similarly offer a means to understand new technology and trumpet its potential. But just as with the earlier examples, the choices that go into their making merit close attention. OpenAI shared the array of headshots to demonstrate the company’s effort to address racial and gender bias in DALL-E 2 images. Through a process the company calls ‘mitigation’, it trained the app to be more inclusive when creating portraits of CEOs, teachers and fire- fighters. In other words, mitigation teaches AI to see people in a different way, which is all for the good. But much like the MacPaint portrait, AI remains a human-machine col- laboration; the application learned how to make portraits through the analysis of images available on the internet. While no individual matches the portraits that DALL-E 2 creates, they are likenesses of our collective identity. Much like a client who rejects an unflattering portrait, we may not like how AI portrays us, or its tendency to generate images that repeat racial and gender stereotypes. But rather than rushing to retrain the machine, perhaps we should look a little longer at the unflattering aspects of AI portraits and consider the mitigations needed to teach humanity to see in different ways. Silicon Valley portraits propose that human figures can help us understand machines. Perhaps we might use AI’s machine portraits to understand ourselves as well.

The engineers Russell and Sigurd Varian, photographed in 1953 by Ansel Adams (1902–84) for LIFE Magazine with a visually arresting but useless contraption. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.