Seven works by Simeon Solomon (1840–1905) were given pride of place in the first gallery of ‘Queer British Art 1861–1967’ at Tate Britain last year. Now the work of the painter, draughtsman and poet launches Christie’s Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist art sale on 11 July and also appears at Sotheby’s parallel sale the following day. Together they make for a rare and comprehensive offering, charting the tragic career of an artist who began as a prodigy feted by the Pre-Raphaelites and ended his days a social pariah living in a workhouse. It is a cruel trick of fate that the scandal that ruined his life has continued to overshadow a complex creative vision more in tune with continental Symbolism than the Victorian tradition.

The catalyst for Solomon’s dramatic reversal in fortunes was his arrest in 1873 at the age of 33. He and a 60-year-old stableman were caught in a public urinal in what is now St Christopher’s Place, off Oxford Street, and charged ‘that they did unlawfully attempt feloniously to commit the abominable Crime of Buggery’. While the stableman was sentenced to 18 months’ hard labour, Solomon, the son of wealthy Anglo-Jewry, was simply fined £100, but the following year was arrested and subsequently jailed in Paris. Unremorseful but tainted by this ‘disgrace’, it seems that he could no longer exhibit at the Royal Academy or in private galleries. The bitter despair – and alcoholism – that ensued ultimately led to the artist’s alienation from most of his friends and family. He did, however, continue to draw in various media – possibly paper was all that he could afford.

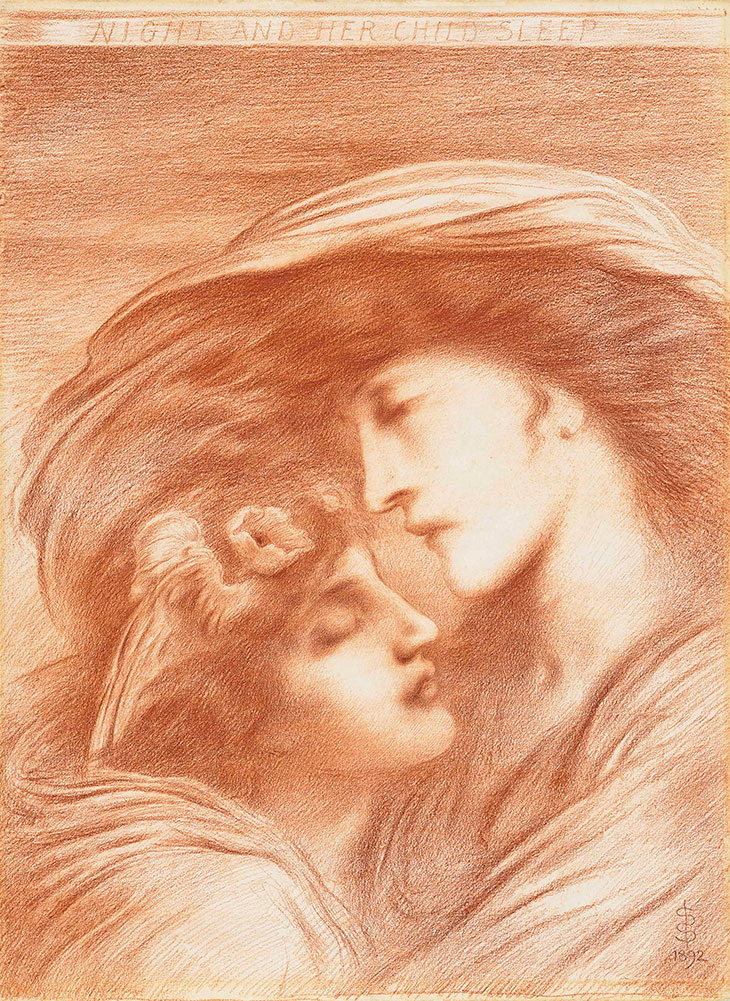

Night and her child Sleep (1893), Simeon Solomon. Courtesy Christie’s

Solomon was a remarkable draughtsman. The Christie’s sale presents 26 sheets from a private collection in pencil, ink, chalk and watercolour. The first lot shows him as an 18-year-old firmly under the sway of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in the hard-edged Love of 1858, one of a series of drawings of medieval subjects (estimate £6,000–£10,000). By his early twenties, he had gained recognition for his paintings of Old Testament subjects, a theme with little precedent in British art, represented in this sale by the likes of Ruth and Boaz, a watercolour of 1862 (£15,000–£20,000).

A fateful meeting with the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne in 1863 seems to have been the inspiration for another turn in artistic direction, as well as prompting Solomon’s most memorable verse. Subjects of classical mythology and allegory appear, all the figures of either or indeterminate sex characterised by a voluptuous sensuality. Some are extraordinarily sensitive single heads, such as the pencil Night. Others are highly charged pairs of androgynous personifications, most notable here Night and her child Sleep, executed in red chalk, which may have been inspired by the opening lines of Shelley’s Queen Mab (£25,000–£35,000).

Habet! In the Coliseum A.D.XC (1865), Simeon Solomon. Courtesy Sotheby’s

Sotheby’s counters with nine more works, not least among them Habet! In the Coliseum A.D.XC. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1865, this is the artist’s largest and most ambitious painting. A group of wealthy Roman women watch from the balcony of a coliseum as gladiators battle below. As the cries of ‘habet, hoc habet!’ (he is down, he has had it!) echo around the amphitheatre, the women make their decision as to whether or not the vanquished should die. The artist offers a variety of reactions to the gore, from horror and swooning to blatant bloodlust – the blonde woman, clutching her necklet and baring her teeth in evident excitement, gives the thumbs down. Most striking of all is the central figure in her blood-red robe, presumably an empress, who has yet to make her decision. Heavy-lidded, full-lipped, she coolly calculates the fate of the defeated gladiator. Lost from sight for almost a century, the canvas was rediscovered in 1996 and now comes to auction with an estimate of £300,000–£500,000.

The Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite and British Impressionist art sale at Christie’s London is on 11 July. The Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite and British Impressionist art sale at Sotheby’s London is on 12 July.