Collectors often say that they only regret ‘the ones that got away’. That feeling of loss at having missed out on something is much the same whether one collects paintings, fossils, sculpture, ceramics or stamps. It only intensifies when the thing being collected is particularly hard to come by, but, conversely, can be relieved by the small triumph of acquiring something else that others have overlooked or not managed to secure. In my own case, these feelings are palpable in relation to (arguably) one of the most niche areas of collecting: bookplates. As a child, I was forever creating collections of things: coins, postcards, badges, stones and even novelty erasers. In adulthood this mindset of acquisition and organisation has been focused, outside my professional life as a museum curator and director, into an enthusiasm for the more specialised domain of bookplates, informed by my love of wood engraving and illustrated books.

A bookplate (or ex libris) is essentially a small print for pasting inside the cover of a book to express ownership. By its very nature it is usually hidden away from view, waiting to be discovered only when a book is taken down from a shelf to be read. In the words of the artist and theatre designer Edward Gordon Craig, ‘a bookplate is to the book what a collar is to the dog’. But, in truth, most bibliophiles who have commissioned a bookplate from a celebrated artist have not done so because they are in the habit of lending their books out to forgetful friends. Rather, the presence of a bookplate is an expression of pride in the ownership of books, whether Bibles, rare first editions or even cookery books – as in the case of Lee Miller, whose husband, the Surrealist artist Roland Penrose, designed a notable example for her collection, depicting the sun and a constellation of stars over the Long Man of Wilmington, the chalk figure close to their home in Sussex.

The bookplate has its origins in the 15th century, especially in Germany, where Albrecht Dürer designed several important early examples. In the 17th to 19th centuries many featured the armorial bearings of members of the aristocracy and aspirational classes, but while these heraldic designs are diligently collected by members of the Bookplate Society, I can’t claim to share their enthusiasm myself – except in the case of a serendipitous discovery of Horace Walpole’s bookplate from the library of Strawberry Hill, which provided a thrill out of all proportion to its diminutive size. Instead, my interest is largely in pictorial bookplates and calligraphic book labels created by modern British artists and illustrators.

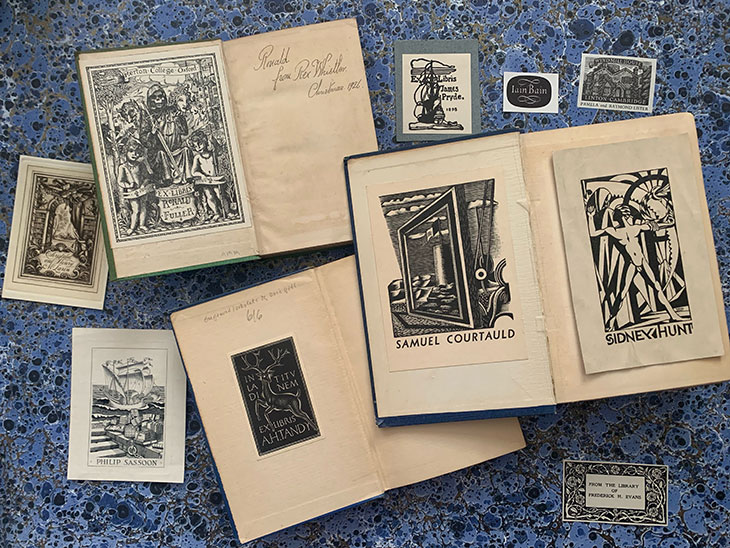

Bookplates by (clockwise from top left): Rex Whistler for Christabel and Henry McLaren, Rex Whistler for Ronald Fuller, Edward Gordon Craig for James Pryde, Leo Wyatt for Iain Bain, Will Carter for Pamela and Raymond Lister, Sidney Hunt for himself, Frederick Evans (based on a book design commissioned from Aubrey Beardsley), Paul Nash for Samuel Courtauld, Eric Gill for A.H. Tandy, and Philip Tilden for Philip Sassoon. Photo: the author

About 15 years ago, I bought a framed impression of Eric Gill’s wood-engraved bookplate for the Sri Lankan philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy, a woodland scene featuring a naked woman and a stag. It struck me that collecting bookplates could be a structured and space-efficient way of acquiring original limited-edition prints, albeit largely unsigned and unnumbered. Before long, I was seeking them out in the bookshops of Charing Cross Road, filling albums and archival sleeves with my acquisitions. During the first lockdown of 2020 it became a welcome distraction from the pandemic, with the bookplates that I had managed to track down arriving on an almost daily basis. Now, I have a collection of several hundred, with examples by 20th-century artists such as Frank Brangwyn, John Craxton, E. McKnight Kauffer, Paul Nash, William Nicholson, John Piper, Enid Marx and Rex Whistler and contemporary artists such as Ian Hamilton Finlay, Paula Rego, Pablo Bronstein and Ed Atkins. Among these there are images of the windmill that became the logo of the publisher William Heinemann, an artist in the landscape (for Stephen and Natasha Spender), a modernist male nude by Sidney Hunt for his own plate, a framed view of a Martello tower (for Samuel Courtauld) and images of country houses and well-furnished libraries, in styles ranging from Arts and Crafts to modernism, neo-Romanticism and Surrealism.

As someone fascinated by the history of collecting, I appreciate how bookplates are an expression of patronage: intensely personal commissions that reflect the interests and mind of the collector. They lead you down rabbit holes as you learn about the lives of their commissioners: architects, actors, artists, writers, politicians, philanthropists, publishers and suffragettes. For me, part of the pleasure of collecting bookplates is the detective work that goes into uncovering their story, using a limited number of visual clues. Within this most niche of collecting interests, I find myself forming sub-categories: groups of mythological subjects, architectural motifs, bookplates with visual puns on names, those by historical women artists, femme fatales, homoerotic bookplates and so on. The thespian group includes David Garrick’s plate with Shakespeare’s head depicted atop a rococo cartouche; Ellen Terry’s, designed by Edward Gordon Craig (her son); Noël Coward’s, by his set designer Gladys Calthrop; Ivor Novello’s, by Philip Armstrong Tilden, and Michael Redgrave’s, by Keith Vaughan: each a striking work in its own right.

David Garrick’s bookplate, engraved by John Wood in the 18th century. Photo: the author

I have come to realise that collecting bookplates is not something that can be done in a hurry. One can search for a bookplate for several years without it ever surfacing, and then suddenly a copy appears in an auction or on a bookseller’s list. It requires tenacity and resourcefulness: one has to be prepared to keep looking, and go to lengths that others would not, trawling through reams of inordinately dull bookplates to find a gem hidden in plain sight. One can only dream of finding a copy of John Piper’s bookplate for Sacheverell Sitwell, with the writer’s initials graven on a lead cistern in the gardens of Renishaw; Eric Ravilious’ little oval plate for Roger Bevan, depicting pot plants in a greenhouse; or Dora Carrington’s Bloomsbury cartouche for the writer Lytton Strachey. But I remain hopeful. A question that I am frequently asked is whether I have a bookplate for my own books. The answer is not yet: I must commission one, but the challenge is where to start and what on earth it might feature.

Simon Martin is director of Pallant House Gallery in Chichester.